DEARBORN, Mich. (RNS) — In the Lebanese countryside where church bells and calls to prayer echo together, Harout Bastajian grew up walking to afternoon Mass with his mom, then crossing the street to spend hours with friends at a mosque.

“I used to play with my matchbox cars on the mosque’s carpet frames,” said Bastajian, who now lives in Dearborn, Michigan. “I somehow grew up in the part of Lebanon during the war where Christians (and) Muslims lived in harmony.”

Bastajian’s interfaith upbringing has continued to inspire and motivate his work as an artist. An Armenian Christian, he has helped to restore several churches, including a landmark 19th-century Roman church and an 18th-century Armenian monastery in Lebanon.

But the muralist has come to be known most for the nearly 50 mosque domes he has painted, including in the U.S. Weaving together traditional arabesque patterns, natural motifs and elegant Arabic calligraphy, Bastajian’s work graces dozens of grand mosques, such as Imam Rifaee Mosque, Lebanon’s largest, Nigeria’s Ilorin Mosque and the Islamic Association of Greater Detroit (IAGD).

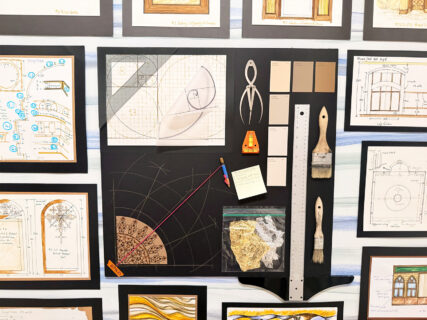

A new exhibition at the Arab American National Museum in Michigan celebrates these domes and offers visitors an intimate look at Bastajian’s large-scale designs through original panels and photographic displays.

“It’s the pride of the community that we are in America and we brought our culture, our art here, and we’re putting it in a nice display,” Bastajian said. “The best place to put your history is the museum or the house of worship where all the people come together.”

The artist has not always worked in sacred places. For years after studying interior design in college, he painted murals for palaces and mansions owned by Middle Eastern mafias and politicians. Now, he said he is “lucky” his work is fulfilling.

Artist Harout Bastajian poses with a variety of his work on display at the Arab American National Museum, Thursday, Sept. 25, 2025, in Dearborn, Mich. (Photo by Ulaa Kuziez)

“I am doing something for the house of God, not somebody’s house,” Bastajian said.

Father Hrant Kevorkian was among dozens of attendees at the opening night for Bastajian’s exhibition on Sept. 25. Kevorkian, the pastor at St. Sarkis Armenian Apostolic Church in Dearborn, first saw Bastajian’s work nearly 15 years ago at the Islamic Center of America, one of the largest mosques in the country which sits adjacent to Kevorkian’s church.

They met many years later when Bastajian moved to Dearborn and came to Kevorkian’s church for Sunday Mass. Since then, the two Armenian men have become friends.

“It’s his passion. It’s a God-given gift that he wants to give back to God, and that’s how I see it,” Kevorkian said, adding that Bastajian is designing a cross for the church.

Bastajian conceives each project from the ground level where worshippers will view the art. He said it sometimes takes months to come up with a design that blends his own artistic touch with traditional styles appropriate for a particular sect and ethnic group. Islamic art avoids physical representation of animated beings in places of worship. Instead, Muslim artists across ethnic backgrounds developed elaborate geometric designs, ornamental Arabic calligraphy and natural motifs. Bastajian said those elements together are meant to remind worshippers of the divine.

“God created this world filled with beauty and harmony. And calligraphy and floral representation can connect a person with God,” said Zulfiqar Ali Shah, the director of religious affairs at IAGD. “So when you enter a mosque, the coloring scheme, the carpet, the woodwork, the calligraphy — all of them take you away and you transcend the concerns of the material world.”

The “Art of Spiritual Enlightenment” exhibition, on display until December, traces Bastajian’s artistic process and showcases the sometimes risky task of painting mosque domes as high as 150 feet.

Mark Mulder, a curator at the museum who worked with Bastajian over the summer to create the displays, said he hopes people engage with the exhibition “and then apply something that they take to their life.”

For Mulder, the exhibition is a lesson in compassion.

“It’s a lesson in caring, but it’s also that you don’t have to belong to a group to learn about them, to understand them and to care about them and to produce things for them,” Mulder said.

Artist Harout Bastajian, center, visits with guests, including Father Hrant Kevorkian, right, during the opening of “The Art of Spiritual Enlightenment” exhibition at the Arab American National Museum, Thursday, Sept. 25, 2025, in Dearborn, Mich. (Photo by Ulaa Kuziez)