(RNS) — Palestinian Christians living in Israel and the West Bank may not have suffered the calamities inflicted on Gaza these past two years, but they, too, have been traumatized by the punishing war.

Israel controls all access to the Gaza Strip and determines what kind of relief, if any, can be offered. The estimated 200,000 Palestinian Christians in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza have been mostly powerless to help.

“You can’t go in and provide humanitarian aid,” said Samuel Munayer, 27, a Christian theologian and humanitarian aid worker living in Jerusalem. Even advocacy is hazardous. “A lot of Palestinians, specifically in Israel, are very intimidated to do anything related to Gaza because of the threat of surveillance by social media and more.”

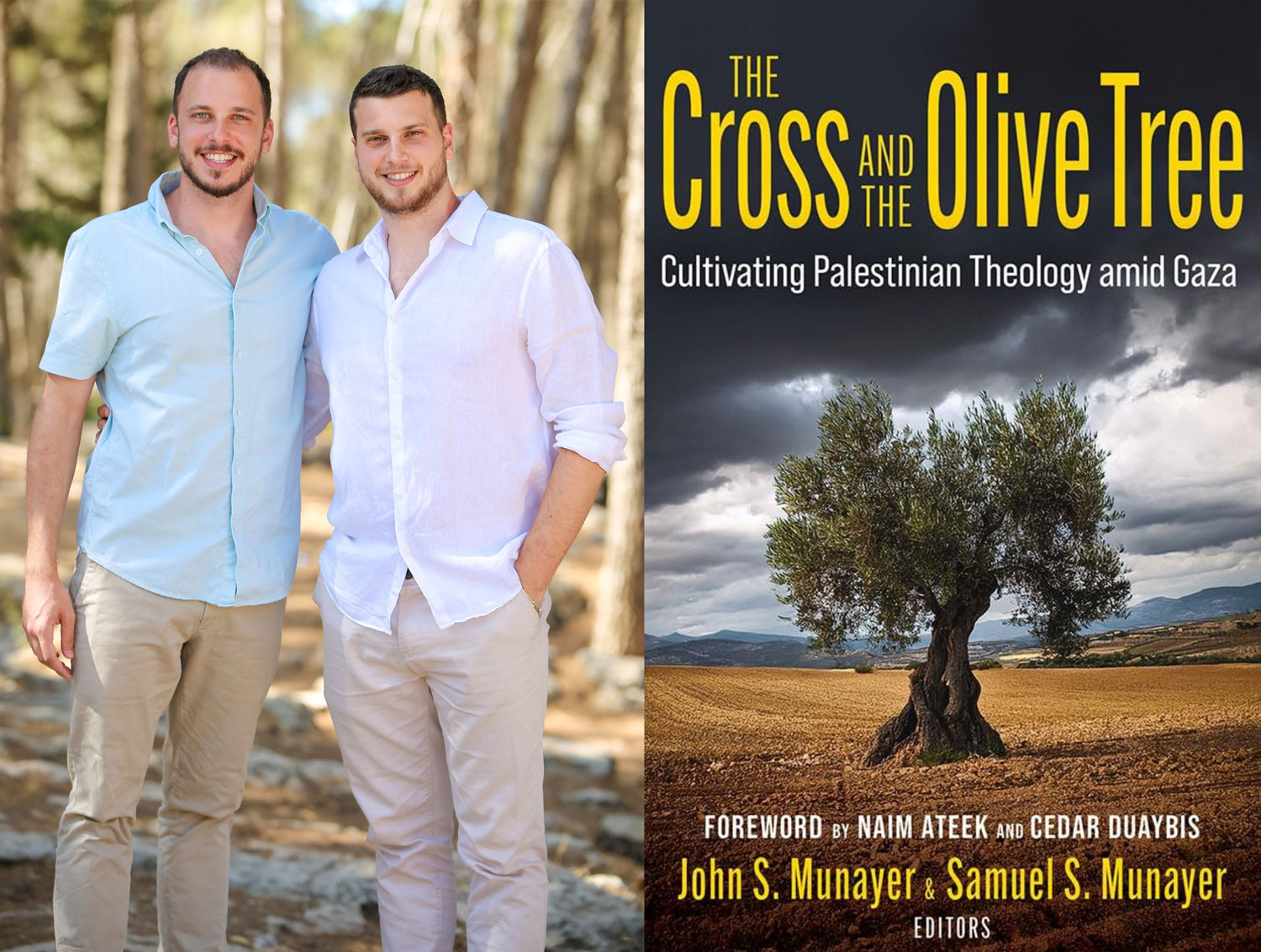

Munayer and his brother John felt they had to do something. So they co-wrote a book, “The Cross and the Olive Tree: Cultivating Palestinian Theology amid Gaza,” published last month by Orbis Books. The slim volume is a collection of essays by young Palestinian Christians in Israel and abroad reflecting on how liberation theology can offer hope in the midst of destruction.

The theology offered by the writers, including the Munayer brothers, is not academic or specialized. “We wish to break out of the assumption that theology is exclusive to those with formal education in churches and universities,” they write in the introduction.

Instead, the book offers meditations on lived theology. The introduction uses olive oil and olive picking as a metaphor for Palestinian theology. One chapter is about the life experiences of two Palestinian grandmothers. Several of the writers are women. One writer compares the assault on Gaza to the mass killing of the Maya Indigenous people during the Guatemalan Civil War, another to the experiences of Black Americans. The writers argue that liberation theology can be a tool for survival, resistance and collective action.

The Munayer brothers — four total — grew up in an ecumenical Christian home in Jerusalem. Their father, Salim, is Greek Orthodox from the central Israeli town of al-Lid, or Lod in Hebrew. Their mother is British. Salim Munayer founded Musalaha, a faith-based organization that trains and facilitates reconciliation mainly between Israelis and Palestinians. The brothers have learned from a range of Christian traditions including evangelicalism and Catholicism.

John and Samuel just concluded a U.S. book tour that took them to Princeton Theological Seminary, Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary, Chicago Liberation Center, the University of Chicago, Wheaton College and beyond. RNS spoke with Samuel Munayer via Zoom about the book and the predicament of Christians in the Holy Land. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Most Gazans are Muslim. How many Christians are in Gaza and where are they?

There are an estimated 400 to 600 left. A large portion are Catholic, sheltering in the Holy Family Church in Gaza City. There’s also a large Greek Orthodox population sheltering at the Church of St. Porphyrius (also in Gaza City).

“The Cross and the Olive Tree: Cultivating Palestinian Theology amid Gaza,” by John and Samuel Munayer. Courtesy Samuel Munayer

You attempt in this book to define a Palestinian theology that is distinct from Christian Zionism. Have Christians in the Holy Land generally bought into Christian Zionism?

There is quite a significant number of evangelical Palestinian Christians who not only have been influenced by Christian Zionism but get direct funding from Christian Zionist organizations. Messianic Jews are also heavily influenced by Christian Zionism, and that has impacted the community in several ways.

Christian Zionism is rooted in colonialism, and many of the Christians in Palestine are also colonized, including myself to a degree, by the logic and the frameworks that Christian Zionism operates in. The clergy many times are not Palestinians themselves. And this kind of colonization and influence by Western Christianity has led to sectarian attitudes towards Muslims. So a lot of Palestinian Christians, especially in the West Bank, believe the problem is with Muslims — Christians are better than Muslims.

You can also see that in terms of identity. A lot of Palestinian Christians within the 1948 (borders) do not see themselves as Palestinians. They have bought into this narrative that to be Palestinian you need to be under Israeli occupation, rather than an Indigenous identity that is connected to land. And the majority of Palestinian Christians do not live in the West Bank. They live in northern Israel in communities like Nazareth, Haifa and the Galilee. So that’s an example of colonization, and the influence of Western Christianity and Christian Zionism is very much evident.

You explain that Palestinian theology evolved slowly. It didn’t emerge immediately after the forced expulsion of Palestinians in 1948. How did it come about?

The elders of Palestinian theology were refugee children in 1948. By 1967, they received training on how to deal with the Christian faith in the Bible that was weaponized for their ethnic cleansing. That ultimately crystallized during the First Intifada in 1987, when this grassroots movement of Palestinian voices was heard on the international scene for the first time and had a language to name and articulate a theology that offers a counter hermeneutic to Zionism in all its forms.

You and your brother wrote a chapter on martyrdom. Explain what you mean by that.

We define martyrdom as being witness to something. Being a witness comes at a cost — not only death, it could be social exclusion, financial damages, a life of sacrifice. The Greek and Arabic understanding of martyrs is as witness, both to the Gospel, the good news, Jesus and also to the evil and oppression of the world.

A Palestinian Christian who decides to stay in Palestine, despite the temptations to leave it to the United States, for example, would participate in that martyrdom, in that witnessing to Christ and to the world. We describe it as a trial. My own family received death threats in the first few weeks (after) October 7th. We faced these big questions of do we stay, do we leave? Do we speak out? These are questions of martyrdom.

Who threatened your family?

For security reasons, I’d rather not say. It’s a group which is known to be quite violent in its hate towards Palestinians. They visited the offices of my brother and my father in Jerusalem, and luckily my father and my brother weren’t there at the time. We were fearful.

Did you consider leaving?

Our family discussions were not necessarily about leaving, but what if something happens? Where do we go for safety? These were the early weeks after October 7th. Things were very uncertain, but there was a strong determination to stay. And it’s exactly in these times that we felt our faith come alive.

Why do you stay?

I stay because I have a duty to be here in the land and kind of a witness that I feel I’m called to be for my faith. I stay because my family has been here for thousands of years and I do not want to run away. I want to fulfill my role as a decent human being to people I love. I want to work for a vision of a future where all people can be in the land in dignity, freedom and peace. And I love my home. I love the people who are here. I am fulfilling that mandate of loving God and loving the neighbor.

How can Palestinian liberation theology help?

Palestinian liberation theology gives language and insight — a certain inspiration and imagination to articulate a different future. The theology, as we describe it, olive picking, is one that brings people together. It’s a spirituality that transcends the self and is rooted in community and in the land. It’s in how we eat food together, how we cultivate land. That sort of spirituality allows people to persevere and be resilient and resist and affirm their humanity. And that’s very powerful, not only to Palestine, but around the world.

This book is inspired by other liberation theologies. It’s a common language and inspiration that has managed to affirm people after decades of oppression and genocide. It is something that cannot be extinguished. Theology gives you that language, gives you the tools to not only critique empire, but to build an alternative. That is something I hope the book inspires people to do.