(RNS) — Taylor Yoder, who grew up in an evangelical Christian family in southern Pennsylvania, was active in her church and its youth group. But as a young adult, she found that friendships with LGBTQ co-workers at a Starbucks caused her to reexamine what she’d been told about homosexuality. “Do I really believe that these people deserve to burn in hell just because they don’t believe like me?” she asked herself.

When her family embraced Donald Trump, she continued to unpack, or “deconstruct,” her faith. “What upsets me most is how politics has become so intertwined with the church,” said Yoder. “It turned a lot of evangelicals in my life really ugly.”

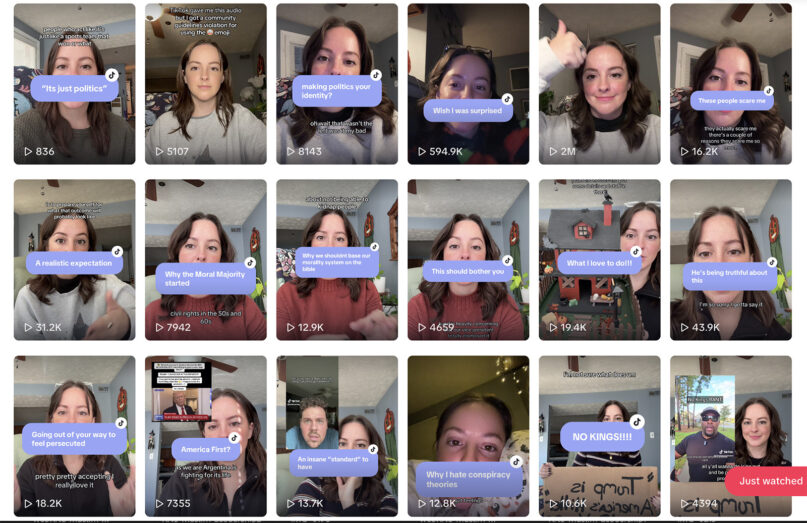

Today, at 31, she is an atheist, and one of many formerly evangelical young women who are disengaging from religion, and at higher rates than their male counterparts. Under the handle “skeptical_heretic,” she critiques evangelicalism and its political ties in videos on TikTok, gaining some 240,000 followers — enough to earn a living.

But the cost has been steep: She’s barely in touch with her family, who warn she’s bound for hell.

In this, too, Yoder is part of a trend: “Exvangelical” women have generated a flurry of memoirs, podcasts, social media posts and YouTube channels depicting evangelical culture as oppressive, unhealthy and even harmful. Their critiques converge on four themes: politics, patriarchy, abuse and the treatment of LGBTQ people. They tell of churches rallying behind Trump, keeping women out of leadership and instead promoting a culture of “purity,” while failing to address abuse scandals exposed in the #ChurchToo movement that followed #MeToo.

Some, like Yoder, have abandoned their faith entirely. Others still follow Jesus but seek to reclaim what they believe is a purer, more inclusive version of the faith. The latter are moving to more progressive churches, though many who have trouble finding a church often meet in private homes.

Taylor Yoder was raised in an evangelical family but has left the church after a process of reexamining or “deconstructing” her faith. She is among a wave of “exvangelical” women who are critiquing the evangelical church and have left their congregations. (Photo by Malcolm Foster)

But their outspokenness makes these dissenting women different from others who have left the church in the decades-long decline in institutional faith. Their exits could be catalysts for revival in the wider church; some even wonder if the early seeds for another Reformation are being planted.

“I think God is raising up women to speak out,” said Amy Hawk, author of “The Judas Effect: How Evangelicals Betrayed Jesus for Power.” “God is allowing this so that we can see the corruption and step away from it.”

Ever since publishing the book, Hawk has been generating social media videos in which she argues, Bible in hand, that it is unbiblical to support Trump. This has made her a beacon for women who have left the church. “Many are coming to me and saying, ‘Thank you, I thought I was going out of my mind.’”

April Ajoy was jolted when she spotted a former church acquaintance on TV storming the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, under Christian nationalist flags. When Ajoy’s brother came out as gay, her own evangelical faith was shaken. “I spent nights crying because I felt so alone and confused, questioning if everything I ever believed was a lie,” she said, and only later recalled things she’d said to others. “I didn’t realize my own hypocrisy in the middle of it,” said Ajoy. “I feel like the evangelical God is in a very tiny box.” Her book, “Star-Spangled Jesus: Leaving Christian Nationalism and Finding a True Faith,” was published last year.

Therapists say they are seeing a wave of women — but few men — wrestling with this process, dealing with everything from self-doubt to loss of relationships they have left behind. “It’s almost an identity crisis of, ‘Who am I? What do I believe?’” said Natalee Gaddini-Birdwell, a California marriage and family therapist who has seen an increase in women in their 30s, 40s and 50s coming to her for help navigating these changes.

In her period of deconstructing, Yoder traveled to Europe and Thailand and watched hundreds of YouTube videos about the making of the Bible and other religious topics. As the doubts piled up, she still faced a wrenching decision: Abandoning her faith, she said, meant abandoning any idea of seeing her deceased father again in heaven.

A variety of TikTok videos by Taylor Yoder, who publishes under @skeptical_heretic. (Screen grab)

But Yoder said she feels less judgmental since she broke with evangelicalism and is freed from the “us-vs.-them” mentality that she saw most recently in the depictions of slain conservative activist Charlie Kirk as a martyr. “He embodies this idea that there’s no separation between politics and religion, and the patriarchal system that that comes from,” Yoder said. “He embodies how hateful and divisive they can be toward LGBTQ people. He was very much the opposite of what I wanted to be a part of.”

According to the Public Religion Research Institute, 40% of women ages 18-29 are religiously unaffiliated — a percentage that for the first time outpaces the unaffiliated rate for young men, which has remained at about 35%. While denominational affiliation and church attendance have been declining for decades across the religious landscape, only leveling off in recent months, according to the Pew Research Center, research from PRRI suggests that exvangelicals are disproportionately female: 58%, compared with 42% who are men.

Their reasons vary: 80% say they no longer believe their religion’s teachings, 58% cite anti-LGBTQ views, while half say their faith harmed their mental health.

In modern American culture, where young women are urged to shoot for the top in business, politics and sports, the bans on female leadership in conservative churches seem out of step. “Those sorts of messages are not going to comport with young women today,” says Melissa Deckman, CEO of PRRI.

Beth Allison Barr. (Photo by Dust in the Wind Photography)

Beth Allison Barr, a Baylor University historian who chronicles women’s roles in the early and medieval church, said she has talked with many frustrated Christian women across the country. “Women don’t see a place for themselves in the church,” Barr said. “They don’t hear women-elevated stories. They do not feel like their callings are appreciated.”

In her 2021 book, “The Making of Biblical Womanhood,” Barr argues that bans on female church leadership stem from flawed biblical interpretations and reinforce harmful hierarchies. The issue prompted her and her husband, a Baptist minister, to leave their evangelical church in Texas a few years ago. They are now part of a smaller Baptist denomination that, unlike the Southern Baptist Convention, favors the ordination of women.

Christa Brown, raised Southern Baptist in Texas in the 1960s, said she loved her church until a youth pastor began abusing her when she was a teen. Speaking out decades later, she discovered how resistant her denomination was to holding pastors accountable. Her 2024 memoir, “Baptistland,” describes evangelicalism as a “culture of domination” rooted in male authority and a lack of accountability.

“When you weld those two elements together, this creates a Frankenstein monster that inflicts enormous harm,” said Brown, now an advocate for survivors.

The 2022 results of an independent investigation commissioned by the SBC revealed a list of dozens of pastors and others accused of abuse since 2000 and described how key church leaders ignored or dismissed sex abuse survivors. The SBC has come under fire for doing little to act on these findings. Brown is one of many SBC survivors who have pressed the SBC to build a database of credibly accused perpetrators — a promise still unfulfilled.

The SBC says it is taking steps to combat abuse, setting up a helpline to report allegations of abuse and crafting a training curriculum to help church staffers and parents recognize grooming behaviors or other signs of potential abuse. “We’re taking this very seriously and developing holistic resources to support churches so that they are the safest places for kids and the vulnerable so they can hear the gospel and grow in Christ,” said Jeff Dalrymple, who was hired in January as the SBC’s director of abuse prevention and response.

For many women, Trump’s rise — and evangelical support for him — was a turning point. About 80% of white evangelical Protestants voted for him in the past three presidential elections.

(Photo by Rosie Fraser/Unsplash/Creative Commons)

Hawk, who led a ministry to women living in shelters at her church in Spokane, Washington, was devastated in 2016 when church friends rallied around Trump despite his bragging about groping women in the “Access Hollywood” tape.

“I honestly could not believe that the church was holding him up as anybody besides a con man and an abuser,” Hawk recalled. “I spent all those years ministering to women, being the hands and feet of Jesus, and then the church is telling me I should be excited about somebody that attacks women.”

She and her husband left their church in 2020. “I believe God led us out of evangelicalism when it became unhealthy,” she said.

For many women, white evangelicals’ embrace of Trump is not only a betrayal of Christian values but a revelation of their true priorities: power and patriarchal masculinity. “Evangelicals were salivating for a macho man to run everything. That is so classic,” said Anna Katherine Britton, who goes by “deconstructiongirl” on Instagram, where she has more than 100,000 followers. “Once I started to see that, it just all made sense.”

Many times, the patriarchy women face in church isn’t overt, said Liz Cooledge Jenkins, whose book “Nice Churchy Patriarchy” is a litany of incremental restrictions she faced as a staffer at an evangelical congregation in California. “For women in a patriarchal system, daily life is made up of ordinary instance after ordinary instance of being underestimated and under-appreciated,” Jenkins writes. “This is the exact opposite of Jesus’ impact on people who found themselves on the wrong side of the power structures of his day.”

Jenkins, who now attends a Presbyterian Church (USA) congregation with a female pastor in Seattle, said the typical hierarchal model of churches simply doesn’t appeal to many women, who want more of a communal experience “where we figure out things together.”

It’s a model that is giving exvangelical women a second chance at spiritual fulfillment. Stephanie Stalvey, an artist raised in a missionary family, said her deconstruction experience has led her to love Jesus more. Nursing her infant son, she recalled Jesus’ words at the Last Supper — “This is my body, broken for you” — and imagined God as a mother. Her forthcoming graphic novel-style autobiography, “Everything in Color,” explores these feminine images of faith.

Sheila Wray Gregoire, a Christian author of books about sex and marriage, likens the stories of exvangelical women to the early stages of the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s.

It’s a “rejection of Christianity as being about power,” Gregoire said. “I think that’s where we are, where people are dissatisfied with the church as it is. What’s coming hasn’t come yet. And we can’t see what that’s going to look like. But it’s an exciting place to be.”