(RNS) — When friends mention some new Christian artwork, movie or novel, I confess my first thought is usually, “I wonder how bad it is.”

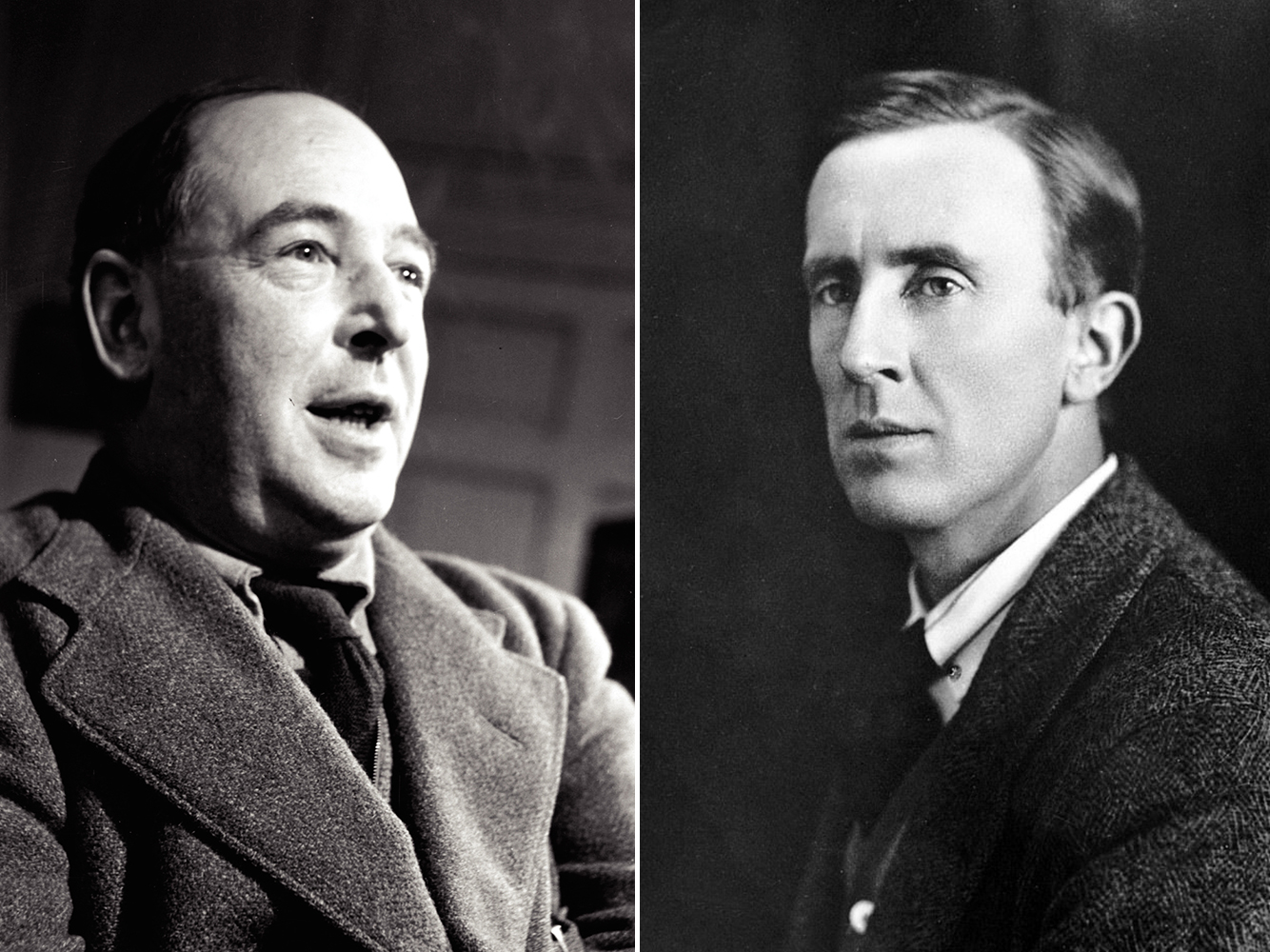

It’s not the artistic treatment of faith that discourages me. J.R.R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis were profound storytellers whose narrative, and their power to narrate, was enhanced by their faith. But neither is commonly called a “Christian writer,” nor are their books limited to the Christian shelves of bookstores. To do so would be to diminish their reach.

Art worth seeing or reading, in short, needs no qualifier. It stands and falls on excellence alone. Their faith places them squarely within one of the greatest narrative and literary traditions in history — that line of artists for whom the Bible is at the center of their education. But they never limited themselves to Christian texts: They immersed themselves in ancient languages, art, myths, parables and plays. Tolkien went so far as to create his own languages and creation narrative in his “The Silmarillion.” Lewis created a world called Narnia that is so compelling to us — despite being crafted primarily for children — that we can’t seem to help returning to it.

They were profoundly accomplished readers, writers and thinkers with a broad and abiding popularity, but an undeniably biblical imagination underpins their respective works.

Tolkien drew deeply from the Bible in “The Lord of the Rings.” Frodo’s burden of the One Ring and its power to overcome him symbolizes the darkness of sin. Gandalf’s battle with the Balrog and return echoes Christ’s death and resurrection, as found in the Gospel of John. And Galadriel’s light given to Frodo echoes John 1:5: “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.” Aragorn as the “returning king” recalls the New Testament’s Book of Revelation, which portrays Christ as King of Kings, and Sam’s hope in darkness reflects the Apostle Paul’s Letter to the Romans, in which he discusses enduring present sufferings for future glory. Many other examples abound.

In similar fashion, C.S. Lewis wove biblical themes throughout his “Chronicles of Narnia.” Aslan has often been seen as an image of Christ, willing to sacrifice himself in the haunting story of the first Narnia novel, “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.” Aslan mirrors Christ’s atonement— “the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world” — in the words of John’s gospel. When he appears again to certain children of the Pevensie family, it is a haunting allusion to the resurrection described in the Gospel of Matthew.

These are all books of children, but no less profound for that. They reflect the childlike faith that Jesus calls for in Matthew’s gospel: “Unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.”

Though Tolkien and Lewis were bound by friendship and faith, their creative and theological visions often diverged. Tolkien, a devout Catholic, distrusted allegory and preferred sub-creation — worlds that hinted at divine truth without direct symbolism. Lewis, an Anglican apologist, embraced allegory. Making Aslan a Christ figure whose actions overtly retold the Gospel is a perfect example.

Philosophically, Tolkien emphasized providence and myth as veiled truth, while Lewis emphasized clarity and accessibility of doctrine. Their tensions reveal a deeper harmony: God’s truth can shine through both mythic subtlety and allegorical boldness, reminding us that divine beauty is not confined to a single style of expression.

That tension, and its harmony, is part of the enduring appeal of their relationship for those who take faith and art seriously. It’s why we’ve returned to their letters, their works and even speculated about their friendship for so long.

At Museum of the Bible in Washington, an exhibition, “Lewis & Tolkien,” explores, among other things, their shared grounding in the beauty and solidity of Scripture — despite sometimes great suffering and personal difference.

At the museum, we realized that too often Christians allow art works’ overt religious messaging to diminish their artistry. That is beginning to change. Streaming series such as “The Chosen” and “House of David” are receiving widespread acclaim because of their production quality and masterful storytelling. We know — because we have seen — that the Bible and deep religious faith can be the basis for great artistic work. Lewis and Tolkien stand as powerful contemporary examples of its enduring relevance.

What remains is one of the few things in which I have an unshakable hope: The enduring power of the Bible and its capacity to shape lives and inspire profound art in those who love it.

(Carlos Campo is the CEO at Museum of the Bible. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)