Pope Francis adjusts his glasses in front of his chair, which has an image of the Shroud of Turin woven into the red fabric, as he leads a Mass during a two-day pastoral visit in Turin, Italy, on June 21, 2015. Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Giorgio Perottino

(RNS) Pope Francis is one of the most popular leaders on the planet, and one of the most outspoken, so his visit to the White House next week, followed by a speech before a joint meeting of Congress — the first by a Roman pontiff — has prompted a tsunami of speculation about what he will say, and which party could benefit most from the historic event.

Democrats and liberals, for example, argue that his focus on economic justice and climate change and immigration will boost their agenda, while Republicans and conservatives say his opposition to abortion and gay marriage and support for religious freedom will make them look good.

Still others say it’ll be a wash because neither party’s platform fits neatly into a Catholic framework. Besides, they say, Francis is a pastor, not a politician, and his remarks to the House and Senate on Thursday (Sept. 24) will avoid specifics and will instead focus on high-minded principles that everyone can get behind without exposing them to political risk.

It’s basically a photo-op, a chance to bask in the reflected glow of “the people’s pope,” and then it’s back to blocking the other party’s bills from becoming law.

But none of those calculations take into account what may be the pope’s real challenge to America’s elected leaders: namely, that they should cut the sanctimony and start compromising in order to pass legislation, even if it’s not perfect.

“In the world it’s difficult to do good in a society without getting your hands or your heart a little dirty,” Francis said in April in an off-the-cuff chat with young Italians about the importance of Catholics going into politics. “But that is why you go ask for forgiveness, you ask for pardon and continue to do it. Don’t allow this to discourage you.”

READ: Francis’ visit to East Coast bypasses Catholic growth centers

Francis quoted one of his predecessors, Pope Paul VI, who called politics “the highest and most effective form of charity.” He warned believers against disengaging from political activity or forming single-minded interest groups that refuse to compromise for the greater good.

Politics, Pope Francis said, “is a daily martyrdom: seeking the common good without letting yourself be corrupted.” But, he continued, “Seek the common good by thinking of the most fitting ways for this, the most fitting means. Seek the common good by working for the little things. … It gives little return, but one does it. Politics is important: small politics and big politics.”

That may sound like commonsense political wisdom. But the pope’s remarks — which he has repeated elsewhere — are notable in the context of his U.S. trip for two reasons.

READ: Pope Francis will test his diplomacy on US tour

The first is that Francis’ approach goes against the gridlock mentality that prevails in an American political atmosphere that is often based on appeals to stand firm on principle, or to the baser instincts of self-interest and partisanship.

Whatever the motivation, the end result has been the same: regular “high noon” showdowns that have left all sorts of bills that the Catholic Church supports dead on the floor of Congress.

Indeed, Republicans who control both the House and Senate are currently scrambling to avert another shutdown of the federal government, this time over a vote on defunding Planned Parenthood — a moment of truth that will arrive just a week after Francis leaves.

READ: In choosing the name ‘Francis,’ new pope sent a clear message

The pope is, of course, very principled. But he is no partisan. He is, instead, deeply political in the sense that he believes Christians must work for redemption even as they live in a fallen world. As he has written, “(r)ealities are more important than ideas,” and therefore Catholics must not be ideologues but should reject “angelic forms of purity … empty rhetoric, objectives more ideal than real, brands of ahistorical fundamentalism.”

That kind of language points to the other reason that Francis’ approach is so timely: His views run counter to a popular view of religion as inherently detrimental to American politics — a shrill, uncompromising voice that prefers to say “no” to everything rather than “yes” to some things.

In recent decades, under the influence of the more conservative views of Saint Pope John Paul II and Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, many American Catholics also succumbed to that hard-line mentality, which actually runs counter to the traditional Catholic approach to the public square.

READ: 13 best reads for understanding Pope Francis

As church historian Massimo Faggioli noted, the Vatican’s insistence that Catholic public policy must instead pivot on a couple of “non-negotiable” items — principally opposition to abortion and, increasingly, gay rights — “contributed to keeping Catholics distant from politics rather than influencing the quality of their political engagement.”

For Rome in recent years, wrote Faggioli, a professor at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, “politics had become the most dangerous of human activities” and could only be engaged with an all-or-nothing approach. Francis, on the other hand, is a “centrist” who “mistrusts both political and religious extremism.”

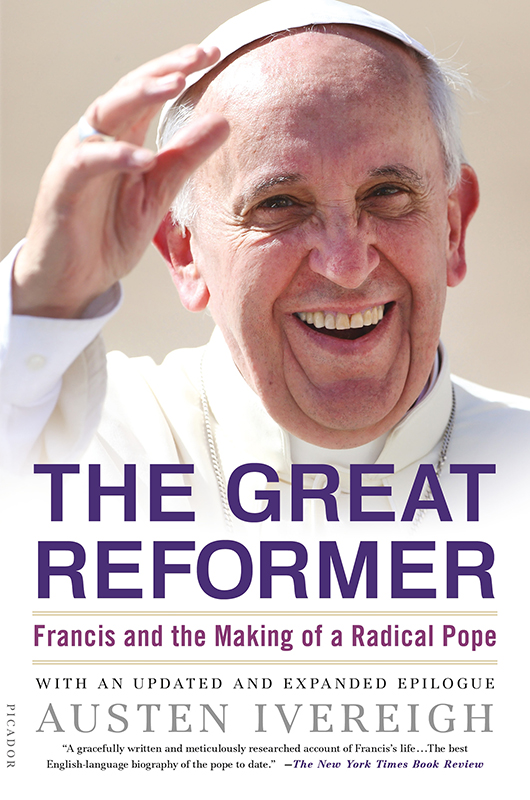

“The Great Reformer: Francis and the Making of a Radical Pope,” by Austen Ivereigh. Photo courtesy of Picador Publicity

He is also himself “a deeply political animal,” as Austen Ivereigh, author of an acclaimed Francis biography, “The Great Reformer,” put it in a recent lecture in Chicago. This pope wants change, and he wants “a healthy politics” that can push that change forward by holding opposites in tension until they can produce unity, not division.

Moreover, Francis has set an example for politicians in how he is running the Catholic Church.

He has put the Vatican back in center stage in international relations, playing a role, for example, in the Havana-Washington diplomatic breakthrough that he is celebrating by traveling to Cuba before coming to the U.S. His groundbreaking encyclical on the environment was intentionally aimed at affecting the next round of global climate change talks in Paris in December, and that document, Laudato Si’, is almost a treatise on effective political engagement.

In fact, Francis and his aides have made a point of working with allies from across the spectrum to advance common causes, such as fighting global warming. That strategy has prompted sharp criticism from some conservative Catholics, who say the church should hew to the earlier line and not consort with people or groups who hold different views on, for example, abortion and contraception.

READ: How Catholic are US Catholics? It’s all in how you measure

Yet Francis seems not to care about such criticisms; he is using the same approach in working for reforms inside the church, appointing many traditionalists to top posts along with more progressive-minded churchmen.

“Francis wants to include all shades of the political spectrum. This is in contrast to previous popes, who largely promoted men in their own conservative image,” wrote Paul Vallely, author of another Francis biography, “Pope Francis: The Struggle for the Soul of Catholicism.”

In his approach, Francis has been variously compared to the Mona Lisa, whose enigmatic smile hides her real intentions, and to Abraham Lincoln, who sought to reconcile two sides after the Civil War. Some call him a chess master who is always thinking several moves ahead of his opponents. A former press secretary, referring to the complicated HBO fantasy drama about warring clans, has said the pope’s “head is like a ‘Game of Thrones,’ in a good way.”

READ: Look for a ‘Francis effect’ at the voting booth, not in the pews

Ivereigh called him “the greatest Argentine politician since (Juan) Peron,” the country’s late, iconic leader and said Francis’ fellow Jesuit priests “refer to him as an unusual mixture of a desert saint and Machiavelli.”

Not surprisingly, those descriptions are not always intended as compliments, and Francis faces enormous political challenges in uniting his own ranks. So it’s not yet clear if his own pontificate could be a model, or a warning, to the Beltway crowd.

But Ivereigh, for one, believes that if Francis chooses to put his vision of a “healthy politics” before a polarized Congress, it could “invite those poles into a fruitful tension” that “could well reshape American political and social discourse.”

Then again, if that happens, you may want to chalk it up to divine intervention as much as political savvy.

LM/AMB END GIBSON