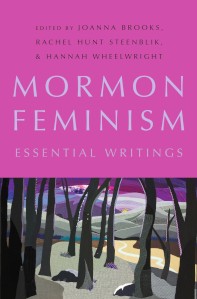

Joanna Brooks, Rachel Hunt Steenblik and Hannah Wheelwright pose together on October 29 in front of the 2012 “Pants Quilt” by Nikki Matthews Hunter. The quilt appears on the cover of their book.

This week marks the publication of an anthology I’ve been waiting for eagerly for over a year now.

Mormon Feminism: Essential Writings gathers up some of the best essays over the last 40 years of Mormon feminism, including the founding of Exponent II and the critical “pink issue” of Dialogue.

The book’s three editors — Joanna Brooks, Rachel Hunt Steenblik and Hannah Wheelwright — say they created this anthology because blogs and podcasts, while valuable, are not enough. “We owe it to ourselves to know our history,” Rachel says.

Here, she and Hannah answer some questions about Mormon feminism: where it’s been and where it’s going. (My marvelous friend Joanna passed the torch to them as the “next generation” for this interview, but this week she did speak to Publishers Weekly about the new book, which you can access here.) — JKR

RNS: It’s an ambitious undertaking to try to sift through more than four decades of Mormon feminist writing. What were your primary goals when you and Joanna made these selections? What qualities were you looking for?

Wheelwright: I spent the summer of 2013 in BYU Special Collections reading all the archives of the Exponent II magazine; it was hard enough to just look at this one publication, let alone the many other sources from which we aggregated the included essentials.

We looked for works that represented the first time an idea or argument had been articulated, that marked a shift in the discourse or scholarship, or that poignantly represented the experiences of many folks who identified it as elemental to their understanding of Mormon feminism and the LDS Church.

RNS: I was particularly glad to see some classic essays get play here: Linda Newell’s 1981 article on Mormon women healing and anointing the sick, and Eloise Bell’s satirical essay “The Meeting.” What were a few of your favorites from the 1970s and 80s?

Hunt Steenblik: I was particularly glad to include them! Linda King Newell’s “A Gift Given, A Gift Taken” is one of my favorites, as well.

I also have deep affinity for Linda Wilcox’s “The Mormon Concept of a Mother in Heaven.” It’s among the first things I read when I was employed by BYU to research Heavenly Mother for what became the BYU Studies article, “A Mother There,” and has stayed with me since. Both seem particularly crucial in light of the recent Gospel Topics essays.

Then there is Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s “Lusterware.” Working on the Mo Fem book was my introduction. I cried and cried when I read Laurel’s suggestion that “If you find any earthly institution that is ten percent divine, embrace it with all your heart!” and again when I read about her standing at the edge of the Mississippi River, experiencing an “infusion of the spirit.”

RNS: What were your favorites from more recent years? (One of mine is 2007’s “The Trouble with Chicken Patriarchy.” Genius.)

Hunt Steenblik: So many. Joanna Brooks’ “Invocation/Benediction,” because “Give me strength to work hours past my daughters’ bedtime” became my prayer while working on the book; Chelsea Shields’ “Dear Mom” for everything; Meghan Raynes’ “Now I Have the Power” because her daughter’s words and actions instill me with hope; and Janan Graham’s “On Black Bodies in White Spaces” for reminding me that the priesthood ban was not only a priesthood ban, but a priesthood and temple ban, which denied exaltation to black women.

I know that two of Joanna’s favorites are Lorie Winder Stromberg’s “Power Hungry” and Lani Wendt Young’s “Rejoice in the Diversity of Our Sisterhood.” One of Hannah’s is Triné Nelson’s “Claim Yourself: Finding Validation and Purpose Without Institutional Approval.”

RNS: There’s been some criticism already about things that have been left out. Stephanie Lauritzen, who founded Wear Pants to Church Day in 2012, wrote that “There is no pain quite like the pain of feeling marginalized within an already marginalized community.” Why did your book not include more about the Wear Pants to Church event? Have you received other criticisms about exclusions?

RNS: There’s been some criticism already about things that have been left out. Stephanie Lauritzen, who founded Wear Pants to Church Day in 2012, wrote that “There is no pain quite like the pain of feeling marginalized within an already marginalized community.” Why did your book not include more about the Wear Pants to Church event? Have you received other criticisms about exclusions?

Wheelwright: While I regret we didn’t include a little more about Wear Pants to Church Day in the beginning of the last section, this work is an anthology, not a history book. The context and historical information we provide are intended to support the writings themselves, not replace them if no articles proved essential.

In our discussions with many members of the community about what pieces represented new thoughts, shifts, and contributions to Mormon feminism, no writings about Wear Pants to Church stood out — I imagine because it was the event itself, the participatory act, that was a turning point for many people.

RNS: What do you think of the Church’s new Gospel Topics essays on women? How have Mormon feminists’ writings through the years helped to prompt the questions being addressed in the essays?

Wheelwright: Church essays are now quoting research by Mormon feminists, whose leadership in this scholarly recovery of Mormon women’s writings has often been ignored.

A church Public Affairs rep attended our first book event in Utah. I had mentioned during the event that while the essays may push some everyday Mormons’ perception of the church, like how the new essay on priesthood speaks of women exercising priesthood authority (!!), it means little if the church doesn’t actively tell members it exists, like how mormonsandgays.org just kind of exists over there without the church actively sharing it as a resource with members on an institutional level. The rep told us afterwards that the church is planning ways to promote the essays more broadly, so I look forward to seeing how they do it, and hope they’ll do the same for mormonsandgays.org.

RNS: What’s next for Mormon feminism? Right now we seem to be characterized by some fissures and disagreements within the movement. Where are things heading?

Wheelwright: I wouldn’t characterize Mormon feminism by fissures/disagreements — I think many folks are very wounded on many levels, from church discipline to disappointment in progressive leaders to trying to heal in their personal life while finding spiritual refuge harder to find at church.

I think more Mormon feminists will speak up about their beliefs on a wide spectrum, and we’ll see more groups and blogs and projects arise as people feel called to focus on specific issues. I hope that together we find more holistic and supportive ways to sustain ourselves as a community in such demanding work.