“The First Fifty Years of Relief Society”

March was both the anniversary of the founding of the Relief Society AND women’s history month, but this woman was too crazy-busy to write about it until now.

I did find time to peruse the fabulous new door-stopping tome The First Fifty Years of Relief Society: Key Documents in Latter-day Saint Women’s History, which was released a few weeks ago.

Before reading this book, I actually thought I knew a little something about nineteenth-century Mormon women’s history. Ha! There were actually lots of interesting things I’d not encountered before.

So I interviewed two of the book’s four editors: Kate Holbrook, Specialist in Women’s History, and Matt Grow, Director of Publications of the Church History Department, to learn more. Here’s an excerpt of our conversation. — JKR

RNS: I had several eye-opening moments when I read this and I had to stop and say, “Wait. What?” (For example, I never knew that Relief Society membership wasn’t automatic like it is today; you had to apply and be known for your good works before being accepted.) Was anything surprising to you?

Holbrook: For me, I didn’t realize how much the Relief Society organization oversaw the development of Primary and Young Women. Relief Society was sort of the umbrella organization for all of it. The general president of the Relief Society was called the “president of the women’s organizations”—the key leader of all the women, and the women’s auxiliary organizations, in the church.

Grow: A surprise for me was how deeply the Relief Society was involved in health care. I had some sense that Mormon women had been sent back east for medical training, but not that individual wards would set women apart under the Relief Society to be midwives. And the Relief Society established a hospital, the Deseret Hospital, that functioned in Salt Lake City in the 1880s.

Minutes from the Nauvoo Relief Society, March 1842 to March 1844. © 2016 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

Holbrook: In looking these documents over, I’ve seen how seriously these women took the Relief Society, and how they saw their purpose as helping the poor and saving souls. You see how seriously they took both those things in the Nauvoo minute books (photo at left). They’d say, “so-and-so is sick down by the river, can’t get out of bed, and her kids don’t have anything to eat.” And then the women would just start volunteering whatever they could do to help the family.

RNS: Tell me about “the ones that got away” — Relief Society ventures that were an important part of the past, like grain storage or sericulture, that we no longer engage in.

Holbrook: I think those activities were really important, and they gave Relief Society members a concrete sense of vision and how to spend their time. They were really meaningful activities in that way. On the other hand, the women weren’t trained to do this work. So they are complicated stories.

When the Relief Society ended up, under duress, selling their wheat to the U.S. government during World War I, the wheat they had gathered were all different varieties and they didn’t all ground up well together. People complained that it wasn’t easy to process or use. Earlier the women delivered their wheat to China when there was famine there, but by the time it arrived it was no longer needed.

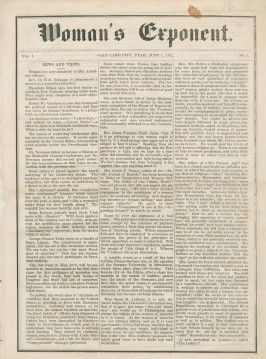

The first issue of the Woman’s Exponent, which ran from 1872 to 1914. © 2016 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

And sericulture was a real challenge. We have a document of diary entries from Jane Blood in Kaysville. She was a Primary president and also in the Relief Society presidency. You can see from the diary how much the sericulture really took over her life. The silkworms always needed more leaves, or you had to do some steps every day to turn it into cloth. It was a huge sacrifice that maybe didn’t pay off in the product, even though it was meaningful for them to be engaged in it and to be working for financial independence in Utah.

RNS: What do the documents have to say about plural marriage in this period?

Holbrook: I saw it more woven into their lives. You see how it impacts their relationships and the way they lead. For example, with the Shipp sisters, one could go to medical school and the other could take care of the children, and then they switched.

Grow: Here’s one thing I found poignant. So often we think about the difficulties of the beginnings, but there were also challenges with the end of plural marriage. Document 4.25 in the book is a stake Relief Society meeting a couple of weeks after the [1890] Manifesto where they are trying to grapple with exactly what that means. Joseph Dean is talking about the reaction in the Tabernacle to the Manifesto:

Many of the saints seemed stunned and confused and hardly knew how to vote, . . . many of the saints refrained from voting either way. . . A great many of the sisters weeped silently, and seemed to feel worse than the brethren. (571).

If you had supported plural marriage and then suddenly that was not going to be happening in the future, that was difficult for families and communities.

RNS: What do the primary sources have to say about the history of women giving blessings and healings?

Holbrook: In the early Nauvoo minutes, you see mention of women having given a healing blessing. And then at the next meeting, Joseph Smith comes and says some people had disparaged this practice of women giving blessings, and he said it was all right. In the April 28, 1842 entry he said, “If the sisters should have faith to heal the sick, let all hold their tongues, and let every thing roll on.”

But over time you see the women start to carefully distinguish between faith healing through prayer and healing blessings given through priesthood authority by the elders. We like to think a lot about healing as a particular spiritual gift. We want to remember that these women were seeking a multitude of spiritual gifts, including healing and charity and speaking in tongues. The gifts were the signs of the followers of Jesus.

RNS: How can women today take strength from or learn from the sisters in the book?

Grow: One of our hopes for the book is that by providing relatively easy access in this document format, and emphasizing that it’s both in print and also online, we’ll see more use of women’s voices and experiences in the cultural life of Latter-day Saints in lessons, talks, manuals, or popular histories. As a culture, we haven’t done a great job in the past of incorporating women’s voices and experiences enough in all sorts of settings, and we hope this is a step in the right direction.

Holbrook: Some qualities that we see -– resilience, flexibility, fortitude — and the examples of the women have been so important to me. The service that I’ve mentioned, just that constant focus outside the household. They cared for the people in their homes and more broadly, they were working to improve life all around the world, for women everywhere. You see women who were nervous about public speaking who then became good speakers.

Sometimes they did things imperfectly, like combining different varieties of wheat. But they used money the US government paid for wheat to improve the quality of maternal and infant care in Utah. So even the imperfect efforts could become important and make a difference.