DURHAM, N.C. (RNS) The first time Rinah Rachel Galper attended a service led by a group called the Hebrew Priestess Institute, she felt bewildered.

Unlike in traditional services, the group sat in a circle. One woman began beating a drum, her rhythms gradually building in intensity. Others got up to dance. In the center of the room stood an altar adorned with a copper bowl and photos of women’s ancestors. God was referred to in the feminine. During one part of the service, women wandered outdoors. Some even kneeled and touched the ground as they prayed.

Rinah Rachel Galper, an ordained Jewish priestess, stands outside her home in Durham, N.C. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

“I had no idea what this was,” said Galper, a Montessori schoolteacher who lives in Durham. “It did not match the Jewish experience I had. Part of me wanted to call it heresy. But part of me knew there was something real and true about it.”

Since that first experience, Galper, 54, has gone to become an ordained Kohenet or Jewish priestess. She leads a weekly Shabbat service in her home for a group of non-Zionist Jews and next month will start an online training program for women seeking to be ordained as Jewish storytellers and spiritual guides.

While male priests called Kohanim performed the temple rituals in ancient Israel, there is no formal role in Jewish tradition for a priestess. In fact, the word does not appear in the Hebrew Bible. But a new movement is attempting to reimagine the role of a holy woman, an intermediary between the human and the divine who is part prophet, liturgist, shaman.

[ad number=”1″]

For inspiration, this Jewish priestess movement looks to biblical women such as Miriam, Moses’ sister, who drums and sings, and Deborah, the judge who held court beneath a palm tree.

It also embraces those ancient Israelite women who worshipped fertility goddesses condemned by the prophets, as well as modern teachings from various Earth-based religions with their healers and ritualists.

This Yom Kippur, as Jews crowd synagogues for the Day of Atonement, some women will gather in a circle for a mix of prayers, chants, songs and meditations — all of which incorporate references to the divine feminine – sometimes known in the Jewish mystical tradition as the Shekhinah.

The 10-year-old Hebrew Priestess Institute has so far ordained 40 women with 50 more in training, many of them Jews who have felt alienated from traditional Judaism — with its masculine depictions of God as king, father, master, lord.

“It’s an antidote to some of the dryness people are experiencing in the Jewish tradition,” said Rabbi Jill Hammer, co-founder of the Kohenet Hebrew Priestess Institute. “Modern Judaism is in deep need of new spiritual resources to inspire people.”

[ad number=”2″]

Hammer has built a program to train Jewish women who want to stake out a leadership path apart from that of a rabbi, an office historically shaped by men (though in Reform, Conservative and Reconstructionist branches of Judaism it now includes lots of women).

The program consists of seven weeklong retreats over the course of three years at either the Isabella Freedman Jewish Retreat Center in Falls Village, Conn., or the Ananda Meditation Retreat in Nevada City, Calif.

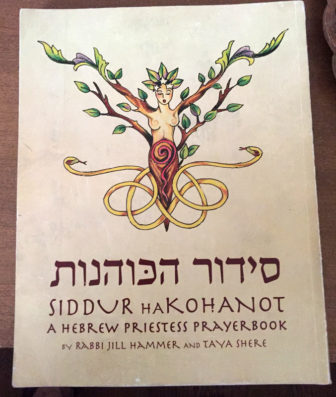

Students are introduced to 13 women’s archetypes or models of female spiritual leadership, including prophetess, weaver, midwife, mother, witch and fool. A prayerbook especially written for the program includes prayers to the divine feminine, which some in the program call the Goddess and others Shekhinah. Rituals encourage participants to move around and use their senses.

Priestess Rinah Rachel Galper uses the Hebrew Priestess Prayerbook during Shabbat services she conducts at her home. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

Graduates are ordained as priestesses, but must find their own creative ways to live out their calling as Jewish spiritual leaders.

Ali Schechter, a 30-year-old dance therapist from Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y., who is in her third year of training to be a priestess, hopes to integrate Jewish spirituality into her dance and movement practice and perhaps conduct life cycle ceremonies, such as bat mitzvahs.

Andrea Jacobson, 71, a psychiatrist who lives in Boulder, Colo., said the training has empowered her to assist her rabbi in creating more meaningful rituals at her synagogue.

Sarah Shamirah Chandler, 37, a New York-based priestess who manages a nonprofit aimed at ending factory farming, loves the program’s emphasis on Judaism’s agricultural past: its feasts and festivals tied to the planting and harvesting seasons.

“The most radical thing about Kohenet is how rooted in tradition it is,” said Chandler.

[ad number=”3″]

Many of the women who have undergone priestess training say they’ve been able to reclaim their Judaism after years spent dabbling in other spiritual practices such as Buddhism, or various Earth-based religions.

Taya Shere, who co-founded the institute with Hammer, had studied religious folklore in South America after college and found meaning in other traditions that elevated the sacred feminine.

“I was so heartened to eventually find that all I needed in terms of spirit — concepts of the sacred feminine as the Goddess and ways of connecting with the Earth and the body — are entirely within Judaism and Jewish practice and possibility,” Shere said.

Shere, who was leading Yom Kippur services for a group of men and women in Berkeley, Calif., on Tuesday and Wednesday (Oct. 11-12), planned to set up various altar stations around the room to allow participants to step away from group prayer for private, meditative space for reflection and the work of repentance. Some of those altars might feature sacred texts such as the Torah, but also stones and divination cards to help people access the spirit.

A group of women dressed in white for an ordination ceremony form a circle on the porch of the Isabella Freedman Retreat Center in Falls Village, Conn. Photo courtesy the Kohenet Hebrew Priestess Institute

For co-founders Hammer and Shere, Israelite and Near Eastern texts are rife with examples of women serving as priestess, whether formally, in non-Israelite societies, or informally in proto-Jewish circles.

But whether goddess worship existed in ancient Israelite society is hard to know, said Jodi Magness, an archaeologist and professor of early Judaism at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

While the Hebrew Bible makes references to devotees of Asherath, which some scholars believe was a female consort to the God of Israel, it does not seem likely a female priesthood conducted that cult, since men would have worshipped her, too.

“Could it be that there existed some worship of female deities and women had a greater roles in ancient societies than we have evidence for?” asked Magness.

“It’s possible,” she said. “But this idea of female-driven society with female goddess and female priestesses serving them, I don’t know of anybody who thinks that’s the case.”

Indeed, women’s leadership roles within Judaism were never significant, neither in early Israelite society, nor later with the development of what is known as modern Judaism.

And that’s a problem for many women.

Galper, who grew up in a Conservative home in Queens, N.Y., announced to her mother in the third grade that she was done with Hebrew school. While she still participated in family celebrations of the Jewish holidays, the male-centric conception of God did not speak to her.

Years later as an adult, an acquaintance accused her of being an anti-Semite during a political discussion about Israel. The accusation shook her sense of identity. She began attending a Jewish meditation class and later took interest in Jewish mysticism and studied with a Hasidic storyteller in New York.

Galper was browsing the Isabella Freedman Jewish Retreat Center website one day six years ago, when she found a reference to the Hebrew Priestess Institute.

“My heart just stopped,” she said. “I knew that was the next leg of my journey.”

Galper was ordained a priestess in 2013.

“I don’t think I could re-engage Judaism without an open door that said I was just as holy as males,” she said. “My doorway to Judaism is understanding that God is as much male and female and neither.”

That ability to cast a wide net and find a range of attributes to describe God, including in feminine terms, is a good thing, said Rabbi Raachel Jurovics, the leader of Yavneh, a Jewish Renewal congregation in Raleigh, N.C.

“We have such a long tradition of text-wrestling and looking at alternative spiritual possibilities that I’m willing to trust people who are respectful of the text and draw new possibilities from it,” Jurovics said.

Galper now feels called to reach out to women and men who have felt similarly estranged from Judaism and help them find a spiritual home.

“It’s taken me years to come into my own skin,” she said. “Kohenet has turned my world upside down, pushed me to new limits, broke me apart and put me back together again and made me what I am.”