CHAPEL HILL, N.C. (RNS) Iranian dissident Mohsen Kadivar and his wife, Zahra “Nikoo” Roodi, have seen it all before.

Late Thursday (Feb. 16), the couple embraced after Kadivar’s hasty return from Berlin, where last month he had begun what he expected would be a semesterlong fellowship.

Instead his plans were cut short by President Trump’s travel ban.

Kadivar, a research professor at Duke University’s Department of Religious Studies, is a permanent resident of the United States. But immigration lawyers and Duke University administrators advised him to leave Berlin and return to the U.S. before the 90-day travel ban affecting seven predominantly Muslim countries, including Iran, expired. Trump vowed Thursday to issue a new immigration executive order next week.

RELATED: Muslim students join lawsuits against Trump

Although federal judges suspended parts of the Jan. 27 ban, Duke lawyers argued Kadivar should take advantage of the legal pause and return home. As an Iranian-born national, it would be safer for him in the United States than risking the possibility he might not be able to return this summer when his fellowship at the Berlin institute was supposed to end, they said.

[ad number=“1”]

Kadivar is no stranger to political turmoil. As an ayatollah, or Shiite Muslim leader, and an outspoken critic of Iran’s hard-line clerical leadership, he spent 18 months in Tehran’s infamous Evin Prison.

“We are not beginners at this,” said Roodi.

But the couple never expected such turbulence in the United States.

“I’m a permanent resident since 2009,” Kadivar said. “I pay taxes. I have a right to be free to return to my home in Chapel Hill and to my office in Durham. This is against American values and the American Constitution.”

Zahra “Nikoo” Roodi and her husband, Mohsen Kadivar, talk in their Chapel Hill, N.C., home on Feb. 16, 2017. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

And so on Monday, Kadivar will return to his office at Duke and try to set aside the monthlong distraction that has prevented him from writing a book — the purpose of his Berlin fellowship.

Duke University joined 16 other private schools earlier this week in filing a friend-of-the-court brief that supports a declaration of the travel ban as “unauthorized by statute and contrary to law.”

[ad number=“2”]

Two weeks earlier, Duke President Richard Brodhead joined 47 other private and public university leaders in signing a letter asking the Trump administration to “rectify or rescind” the controversial executive order.

David Morgan, chairman of Duke’s Department of Religion, said it would be a pity if a new travel order, which Trump said he would announce next week, limits Kadivar’s travel.

“He’s an international figure whose work is recognized around the world,” Morgan said. “It would have a very unfortunate impact on his work.”

A new travel ban would also affect Kadivar’s family. He and his wife have two grown children back in Iran, plus his wife’s 92-year-old mother. While her husband can no longer return to Iran, Roodi was fervently hoping to go herself.

[ad number=“3”]

“It feels like I’m stranded in a large prison,” said Roodi who works at the Emerson Waldorf School in Chapel Hill. “It looks like Mr. Trump is building a wall around the United States before he builds one on the Mexican border.”

Back in 1979, Kadivar was a devotee of the Iranian Revolution that overthrew the Shah and replaced him with an Islamic Republic under the Ayatollah Khomeini.

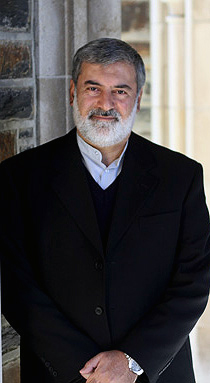

Professor Mohsen Kadivar. Photo courtesy of Kadivar.com

But over time, he became disenchanted with the revolution and worked to reform his country by applying the training he received in Islamic theology, philosophy and ethics.

In 1995, the state began to restrict his actions, first barring him from teaching and later declaring him unqualified to run for a court seat that appoints and monitors Iran’s supreme leader.

After he criticized the murders of Iranian dissidents in a newspaper interview, he was arrested and given an 18-month prison sentence.

In 2007, he accepted a one-year visiting professorship at the University of Virginia. With his bags packed and his goodbyes said, he arrived at Tehran Imam Khomeini Airport only to have his passport confiscated.

The following year, his passport returned, he was asked to leave Iran for good.

Yet despite all the trouble he has faced in Iran, and now in the U.S., Kadivar felt a wave of relief late Thursday as he made it home from the airport, full of compliments for the U.S. judiciary, which was able to stop Trump’s order in its tracks and allow his smooth reentry into the U.S.

“I should thank the federal judges and American civil society,” he said. “Judicial power in the U.S. is one of the best. This is something I will write about — the independence of the judiciary.”

And though he regrets the untimely end of his fellowship — he was just getting to know other scholars at Berlin’s Wissenschaftskolleg institute and was looking forward to learning from and working with them — he remains hopeful.

“In all situations, we as believers, we hope with the faith of God,” he said. “I try to adapt myself to what’s happening.”