FILADELFIA, Paraguay (RNS) Violence tore through this close-knit, traditionally pacifist community on the night of March 11, 1944. All the more remarkable, its perpetrators and victims were all Mennonites. And they all belonged to rival Nazi factions.

Since the end of the Second World War, Mennonite-Nazi collaboration has largely been ignored, forgotten or intentionally repressed. In Paraguay, members of Mennonite congregations were forbidden from discussing the matter.

In Paraguay and beyond, the Nazi episode has been taboo for adherents of this Christian denomination that was founded in 16th-century Europe on principles of nonviolence and nonparticipation in politics.

[ad number=“1”]

Not until the 1980s, when an international search for Auschwitz physician Josef Mengele brought unwanted attention to the German-speaking Mennonite colony of Fernheim in Paraguay’s remote Gran Chaco, did that taboo begin to weaken.

Now Mennonites and others are probing that past in a series of conferences, the most recent of which took place last weekend in Filadelfia, administrative center of the colony.

Spiritual healing, reconciliation and multigenerational guilt were prominent themes at the latest conference, titled “The Racialist Movement and National Socialism among the Mennonites in Paraguay.”

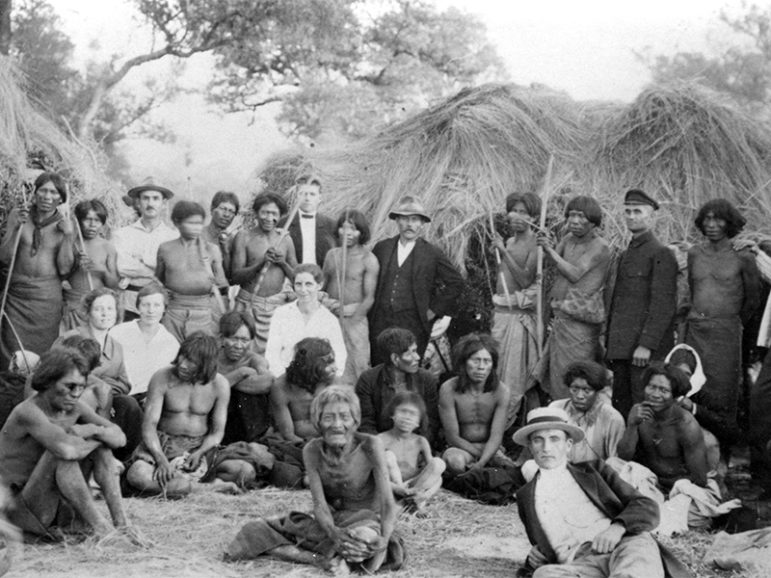

Participants of the Fernheim conference mingle outdoors during a break on March 11, 2017, in Filadelfia, Paraguay. Photo courtesy of Ben Goossen

Some 200 participants gathered near the site of a brawl that had taken place exactly 73 years previously. They sought to bring into the open, contextualize and interpret events that remain painful even after they have mostly passed from living memory.

“Many have asked, why have a conference on this topic, more than 70 years after the events,” said Uwe Friesen, head of the Society for the History and Culture of the Mennonites in Paraguay. In his opening address, Friesen characterized the gathering as offering “the possibility of new understanding.”

[ad number=“2”]

Interest for this dark chapter in Paraguayan Mennonite life comes at a time when the global church is beginning to uncover a larger history of Nazi collaboration.

In 2015, the first academic conference on the topic took place in the German city of Münster, site of the 1534 Münster Rebellion that was crucial to the founding of the Mennonite faith. Historians revealed substantial pro-Nazi movements among communities in Canada, the Netherlands, Paraguay and Brazil. By the height of Hitler’s power, one-fourth of all Mennonites worldwide lived in the Third Reich.

RELATED: Mennonite Church coming apart over sexuality issues

The Münster conference was organized by Germany’s Mennonite Historical Society — itself founded in 1933 in part to support racialist research in the new Nazi state. President Astrid von Schlachta, professor of history at the University of Regensburg, called the event “a truly historical meeting.” The gathering “represented an open and nuanced discussion, in which we judged without condemning the context and experiences of Mennonites in the Nazi period,” she said.

Mennonite settlers in Paraguay’s Fernheim Colony, as refugees from the Soviet Union, were susceptible to Hitler’s platform of nationalism, anti-Bolshevism and anti-Semitism. Here, the Neufeld family celebrates a silver wedding anniversary in 1930. Photo courtesy of Mennonite Library and Archives (North Newton, Kan.)

Given Fernheim’s formerly pro-German stance — along with the arrival of thousands of Mennonite migrants from postwar Europe, including known war criminals — Nazi hunters considered the colony a likely hideout for Mengele. (He was eventually found dead in Brazil.)

Mennonite refugees from the Soviet Union had established Fernheim in 1930, receiving humanitarian assistance from the German government. Three years later, a majority were effusive in their praise for Hitler.

“With great excitement, we German Mennonites of the Paraguayan Chaco too participate in the events of our dear Motherland and experience the national revolution of the German race,” colony leaders wrote in a letter to the Fuehrer.

Nazi officials proposed that they return to Europe, citing Mennonites’ alleged blood purity.

Already, racial anthropologists had tested the Fernheim settlers, finding them more Aryan than the average German. Eighty percent were reportedly prepared to renounce pacifism and join Hitler’s “Home to the Reich” program, an undertaking thwarted by the outbreak of war.

[ad number=“3”]

Cut off from Germany, Fernheim’s residents disagreed about how best to maintain Nazi loyalty. A power struggle ensued that focussed on colony administration, control of the German-language schools and access to return transportation to the Reich. Young men gathered whips and clubs, and they severely beat six competitors. The unrest prompted intervention from U.S. diplomats and the Paraguayan military, ultimately leading to the banishment of several ringleaders.

Three-quarters of a century later, Friesen hopes for healing. “It is important that we consider facts, that we analyze and present events in a way that builds peace, both drawing on and propagating our Anabaptist inheritance,” he said, referring to the pacifist theology once again prominent in Fernheim.

Attendees of the symposium — which featured historians from Paraguay, Germany and the United States — agreed that local tensions should be consigned to history. They also saw the gathering as part of an ongoing conversation.

Discussion will continue at a third conference, on “Mennonites and the Holocaust.” Scheduled for March 2018 at Bethel College in North Newton, Kan., the event is sponsored by Mennonite Church USA, the largest Mennonite denomination in North America.

New evidence has implicated some Mennonites in genocide. Especially in Nazi-occupied Ukraine, large German-speaking colonies drew favor from National Socialists such as Alfred Rosenberg and Heinrich Himmler. Local recruits bolstered death squads, which massacred tens of thousands of Jews in and around the settlements.

Heinrich Himmler (third from right), head of the SS, at a flag-raising ceremony in the Molotschna Mennonite colony in Nazi-occupied Ukraine, 1942. Himmler and other National Socialists praised Mennonites’ allegedly Aryan blood. Photo courtesy of Mennonite Library and Archives (North Newton, Kansas)

“Mennonites have typically seen themselves foremost as victims of violence in the 1930s and ’40s in Europe,” said Mark Jantzen, professor of history at Bethel, “but we hope the conference will document and analyze a much more complex reality that places Mennonites across a whole spectrum of responses, experiences and motivations, along a range of suffering violence to witnessing it and causing it.”

Organizers have called for papers detailing cases of Mennonites aiding Jews and other targeted populations, as well as instances in which members benefited from ethnic cleansing or themselves perpetrated war crimes.

The recent gatherings in Germany and Paraguay have demonstrated a willingness among Mennonites to forgive each other. “Making peace means living out and offering reconciliation,” Friesen said at Fernheim’s symposium.

But the greater and more ecumenical challenge is the church’s responsibility toward non-Mennonite victims of Nazism. The Mennonite World Conference has recently accepted apologies from Lutheran and Catholic bodies regarding persecution of Mennonites during the 16th-century Reformation. Questions of Mennonites’ own collective guilt — during the Nazi period and beyond — remain.

(Ben Goossen is a scholar of global religious history at Harvard University. He is the author of “Chosen Nation: Mennonites and Germany in a Global Era,” to be published in May)