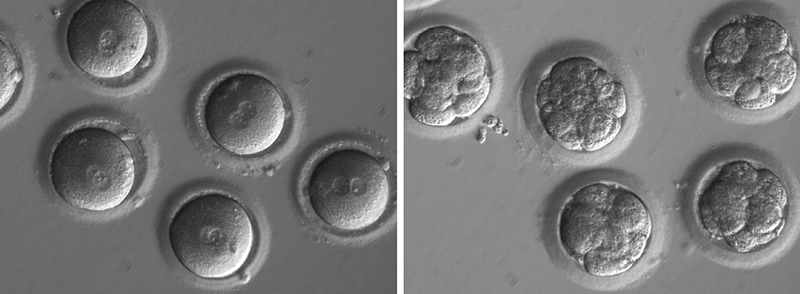

Newly fertilized eggs before gene editing, left, and embryos after gene editing and a few rounds of cell division. Image courtesy of Shoukhrat Mitalipov

(RNS) — News that scientists for the first time successfully edited genes in human embryos created a stir this week.

In the experiment, outlined in a paper in the journal Nature published Wednesday (Aug. 2), scientists essentially snipped a mutant gene known to cause a heart condition that can lead to sudden death.

The work is controversial because it showed that scientists could manipulate life in its earliest stages and that those changes would then be inherited by future generations, if the embryo were allowed to grow into a baby. (The embryo in question was destroyed.)

It also raised the tantalizing promise that the baby would be disease-free and would not transmit the disease to his or her descendants.

[ad number=“1”]

The work, a collaboration by the Salk Institute, Oregon Health and Science University and Korea’s Institute for Basic Science, was performed using private money since the United States forbids the use of federal funds for embryo research.

But it raises a host of ethical questions with religious ramifications. Should these edited embryos be allowed to develop into babies? Could scientists edit out undesirable traits to create customizable “designer babies”? Could it increase inequality in society between those with access to such technology and those without?

Arthur Caplan. Photo by Mike Lovett

Arthur Caplan, the founding head of the Division of Bioethics at New York University, answered some of those questions. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

The gene editing findings are a breakthrough, do you agree?

It’s a breakthrough, but a baby step. It’s a demonstration of proof of principle, meaning you made a correction and didn’t kill the embryo, and as far as you know, it developed normally for a little bit. It still didn’t demonstrate that there weren’t some errors made in other parts of the embryo. That might appear later in development. But it’s certainly an exciting step.

People are now worried about the possibility of creating designer babies. Should they be?

I’m filled with amusement about that worry. The paper that was published was kind of like a demonstration that it’s possible to put a satellite in orbit. The designer baby question is sort of, ‘Can we travel to other galaxies?’ We aren’t very close. It’s not something anybody has to worry about right now. It’s certainly a consideration for our grandchildren, but not for us.

The questions today are: Who’d be watching this technique enough to decide how much safety and evidence there needs to be to try to make a baby using this technique? Who owns the technology and what will they charge people for it? Since most of the prior work on gene editing was funded by taxpayer money, it might be interesting to know if there’s going to be any effort to guarantee access at reasonable prices. The mapping of the human genome and everything that led up to this was publicly funded.

[ad number=“2”]

But this study was done with private money and that raises the possibility that further research can be done privately and maybe even abroad, right?

I will guarantee this technique will move forward. There are other governments in other countries that want to do it: China, Britain, Singapore, Taiwan, Korea. There are plenty of places around the world that would not see much to object to in continuing this work. What the United States does will not be the last word.

The idea that humanity would knowingly move back from the opportunity to prevent diseases from being passed on to future generations is ludicrous. The arguments about perfect babies, mutant humans or eugenics are not going to stop attempts to prevent disease or repair disease.

This genetic engineering concept shows a hand replacing part of a DNA molecule in this 3D rendered illustration. Image via Shutterstock

That’s worrying, isn’t it?

I still think you can try to regulate the technology. It would be nice if we had an international group; set out some rules. It would be great if the scientific community — with religious and ethics and legal leaders — would set up some rules of how to operate. It would be nice if journal editors would say, ‘We’re not publishing anything unless these rules are followed.’ That is important to do.

What are some of the concrete questions such an international group should address?

Where you get your embryos and gametes from; what kind of informed consent would you use to do research? How long can you develop an embryo in a dish? How far can you take it? How much animal work should be done before we attempt to make a baby? What diseases ought to be the top priority to study and work on and why? What are the competencies a team should have to do this? Should we create a registry, so that every experiment with embryos is filed and registered and we know all the outcomes, good and bad? Who pays if a child is born with grave disabilities? Those are the issues. Superbabies? That fear can wait awhile.

[ad number=“3”]

What practical steps can religious groups take?

First, get a scientist in to talk to you — someone who understands this and can tell you where we’re at in engineering embryos in humans and animals.

Second, what is the obligation to pay for this on the part of the government if it’s really oriented toward diseases and their prevention and treatment? Speak up for fair access.

Lastly, religious groups can demand that the scientific community form the kind of oversight body and rules I’m talking about.

It wouldn’t hurt to do one other thing: Try to understand historically — what was Nazi eugenics, what made it so evil? How did it come to pass? It wasn’t because of new technology; it was because of racism and bigotry. If you want to worry about abuse of today’s technology, it’s just as important to be careful about anti-disability views, racism, prejudice. That’s what leads people to misuse technology, not the technology itself.