NAIROBI, Kenya (RNS) – As violence-torn Africa grows weary of solutions that haven’t worked, Nigerian Cardinal John Onaiyekan is proposing a controversial alternative: Negotiate with terrorists.

Onaiyekan, the archbishop of Abuja, has been backing talks with Boko Haram, the violent Islamist militant group operating in the northern parts of the country. Negotiating with terrorists is vehemently opposed by governments in Africa and around the world due to concerns that concessions could inspire more attacks.

Speaking at a recent Nairobi conference of religious leaders from Africa, Europe and Asia, Onaiyekan insisted interfaith dialogue is key to ending the deadly conflicts — even if it means sitting down with ruthless killers.

“My position is no matter how extremist a person is, there must be somebody who can talk to them and others,” Onaiyekan said. “Then eventually talking will start taking place. That will be an easier way of handling grievances than guns.”

Governments in the region have responded militarily to terror threats, but Onaiyekan said it’s time for a new approach.

Sheikh Rashid Omar, left, and Cardinal John Onaiyekan at the religious leaders’ peace and security conference in Nairobi, Kenya, on May 23, 2018. RNS photo by Fredrick Nzwili

“Let us admit that nobody does anything for nothing,” he said, “and there ought to be a forum where people can … explain why.”

He said Muslim leaders in Nigeria can play a pivotal role in bringing Boko Haram to the negotiating table because they share a common faith tradition, albeit one that Boko Haram interprets through an extremist lens.

His proposal was well received among attendees at the conference, which was co-sponsored by a Muslim university and a Roman Catholic one. But it also received pushback in security circles.

“We cannot negotiate with terrorists as long as they continue to use violence to achieve their motives,” said Richard Tutah, a Kenyan homeland security consultant and counterterrorism expert. “They are terrorists because they use violence to terrorize civilians, whether they base it on their religion or otherwise.”

But Tutah conceded negotiations can be permissible in limited circumstances.

“The only time we can negotiate with them as a counter-terror strategy is when they become kidnappers,” Tutah said. “Another instance is when they are willing to put down their arms and convert into a political movement or party. Unless that’s the case, we cannot.”

For nine years, Boko Haram has bombed churches, mosques and government installations in West Africa. The group has carried out assassinations and abductions of women, girls and boys, and justifies the attacks by citing the Quran. In recent years, the group has spread from northern Nigeria to neighboring regions in Chad, Cameroon and Niger.

In its quest to establish strict Islamic law, including a prohibition on girls’ education, Boko Haram has killed thousands. In 2015, President Muhammadu Buhari said 10,000 had already been killed by the group, which has widely employed the use of girl suicide attackers. Roman Catholic Church figures estimate more than 5,000 Catholics have been killed in Nigeria’s predominantly Muslim northern region. More than 900 churches have also been destroyed, according to the Christian Association of Nigeria.

Thus far, Nigeria’s government has been reluctant to negotiate with Boko Haram, but has nonetheless done so on occasion. For instance, the government negotiated some releases after 276 schoolgirls were kidnapped from a government school in April 2014.

Onaiyekan painted the Nigerian government’s response as primarily a military bombardment that has cost millions of dollars, some of which came from foreign assistance funds. More could be accomplished, the cardinal suggested, if those funds were used “to improve relationships and encourage dialogue.”

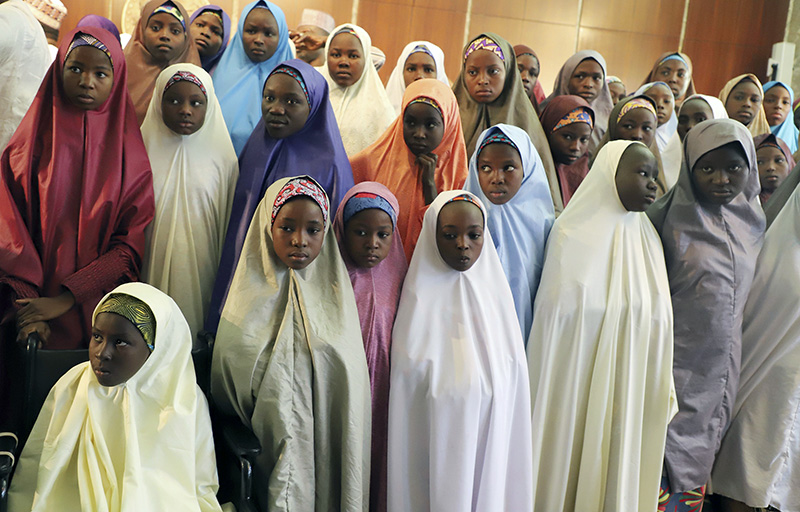

Recently freed school girls from the Government Girls Science and Technical College in Dapchi pose for a photograph after a meeting with Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari at the presidential palace in Abuja, Nigeria, on March 23, 2018. Nigeria’s president welcomed to his official residence more than 100 girls who were released by Boko Haram after being kidnapped a month before. (AP Photo/Azeez Akunleyan)

“The aim is not to kill all Boko Haram, but to arrive at reconciliation so that people can go home to their families,” said Onaiyekan.

Conflicts have been persistent. At least 31 conflicts rooted in Africa’s colonial past remain unresolved, according to the African Union’s Continental Conflict Early Warning System. They range from interethnic wars to Islamist campaigns, border disputes and civil wars.

Religious leaders have been targeted frequently. More than 30 ordained clergypersons have been killed in South Sudan since December 2013 when the latest round of political violence broke out. In the Central African Republic four church leaders have been killed since January. An interfaith group of top Muslim, Catholic and evangelical Protestant leaders has formed in CAR to mobilize faith as a force for peace.

“Unless we confront that past, we shall not resolve these conflicts,” said Francis Kuria Kagema, general secretary of the African Council of Religious Leaders. “Religion is part and parcel of that.”

The two-day conference discussed the role of religion and its contributions to conflict and peacemaking.

To counter religious extremism, faith leaders should study each other’s holy texts, said Sheikh Rashid Omar, Kenya’s deputy chief Kadhi, or high-ranking religious judge in the country’s Islamic courts. By reading each other’s texts, he said, leaders gain a deeper understanding of other groups and aren’t as likely to perpetuate stereotypes that encourage violence. The practice can also help bring extremists back to a practice of true religion, Omar said.

Nigeria wasn’t the only country where conferees see hope for negotiations. They also spoke at length about Somalia where al-Shabab, an Islamist militant group, has used religion to justify attacks in the region. After a decade of efforts from the African Union, Al-Shabab shows signs of being close to defeat, improving chances for dialogue among the Somali people, said Omar.

“They need to talk and agree on some things,” he said, adding that religious entities needed to facilitate the reconciliation.

Omar pointed to Muslim leaders who were ready to rehabilitate Kenyan youth who were returning to their homes after being recruited by al-Shabab. In the past, he said, imams have received former militants in mosques, deradicalized them through Quranic teachings and provided aid before releasing them into the wider community.

Collaboration between African Muslims and Christians is weak, according to Bishop Alfred Rotich, a former Catholic chaplain to the Kenyan military. He urged the leaders of all faiths to unite, consolidate efforts and embark on research on peace and security.

“We must have the voice and prophesy, but first we must work on our inner selves,” Rotich said. “Once we are comfortable, we must strongly speak against violence.”