A liberal Jewish woman in a kippah (yarmulke) listens to Dan Shapiro, a former U.S. ambassador to Israel, call for Jewish unity during an American Jewish Committee event in an archaeological garden near the southern end of the Western Wall on June 13, 2018. RNS photo by Michele Chabin

JERUSALEM (RNS) – In January 2016, Mollie Shichman, a liberal Jew from Fairfax, Va., celebrated the Israeli government’s decision to create the first-ever government-funded pluralistic prayer space at the southern end of the Western Wall.

“To me, being egalitarian is extremely important,” Shichman, a college student, said of the proposed mixed-gender prayer space.

But excitement turned to disappointment when, in June 2017, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu backtracked on the plan due to pressure from ultra-Orthodox lawmakers.

Mollie Shichman. RNS photo by Michele Chabin

In Israel this week (June 10-13) to attend the American Jewish Committee’s Global Forum, Shichman, who wears a kippah (yarmulke), a head covering traditionally worn by Jewish men, recalled being “accosted” by an Orthodox woman at the Western Wall for what the woman considered Shichman’s “immodest” clothing at the Western Wall plaza, a plaza behind the men’s and women’s prayer sections that isn’t used for prayer.

“I was at the far end of the plaza and took off my skirt” after visiting the Western Wall. “I had my shorts on underneath, but she called me a ‘goy,'” Shichman said of the Hebrew word for non-Jew, which the woman hurled as an insult.

“It was very hurtful to me. I’m just as much of a Jew as she is,” Shichman said.

While most Israeli Jews recognize the Jewishness of their American counterparts, the majority do not share the Americans’ dreams to make Israel a more religiously pluralistic country.

Lack of full equality for non-Orthodox Jews in Israel “over time may weaken American Jewish support for Israel,” said Harriet Schleifer, chair of AJC’s Board of Governors.

Two parallel AJC surveys released Sunday revealed “sharp differences of opinion” between Jews in Israel and the U.S., and between religious and liberal Jews in both countries.

“Significantly, for both communities, the main factor predicting how people will respond is how they identify religiously,” said AJC CEO David Harris in a statement.

“The more religiously observant they are on the denominational spectrum, their Jewish identity and attachment to Israel is stronger; skepticism about prospects for peace with the Palestinians higher; and support for religious pluralism in Israel weaker.”

Religious pluralism is a cornerstone for Jews in the U.S., where some 85 percent of the Jewish population defines itself as non-Orthodox or religiously unaffiliated, according to a 2016 survey by the Pew Research Center.

In Israel, where there is no separation between religion and state and where Orthodox Judaism is the only official, government-funded religious authority, 30 percent of Israeli Jews said that non-Orthodox Judaism “strengthens Jewish life in the diaspora but is irrelevant in Israel,” according to the AJC surveys.

A mere 26 percent of Israeli Jews thought the growth of the non-Orthodox streams in Israel can improve the country’s quality of life, compared with 43 percent of American Jews.

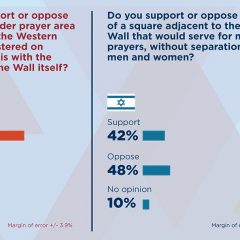

- Graphic courtesy of AJC

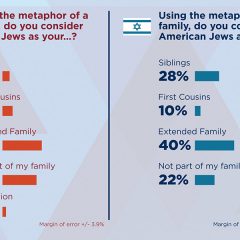

- Graphic courtesy of AJC

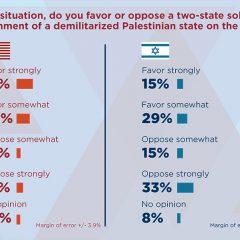

- Graphic courtesy of AJC

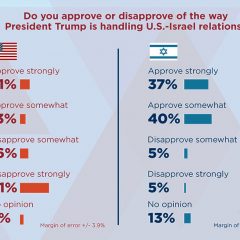

- Graphic courtesy of AJC

In another noteworthy gap, a strong majority of American Jews (73 percent) favored providing a space near the Western Wall for mixed-gender prayer, while 42 percent of Israeli Jews favored it and 48 percent opposed it.

A whopping 80 percent of American Jews vs. 49 percent of Israeli Jews want to end the ultra-Orthodox chief rabbinate’s monopoly on weddings, divorces and conversions.

Steven M. Cohen, a sociologist whose work focuses on the American Jewish community, attributes the “widening gaps” between the world’s two largest Jewish communities to both ethnic and cultural differences.

“They come from very different cultures,” Cohen said. Whereas most American Jews are descended from Jews from Eastern Europe, at least half of Israeli Jews trace their roots directly to the Middle East and North Africa, among other places. They tend to be more religiously conservative.

Cohen said Israelis are highly innovative and pluralistic when it comes to politics, but not religion.

Israeli society has more than a dozen political parties that compete for parliamentary seats, but it continues to allow only the Orthodox establishment to decide on religious matters.

In the U.S., where religion and state are separate, the Reform, Conservative and Orthodox streams are on equal footing.

American Jews “place a much greater premium on universalism and softening group boundaries,” Cohen said. That’s one of the reasons many Jews feel comfortable marrying someone of a different faith.

The high rate of American Jewish intermarriage is a concern to many Orthodox Jews both in the U.S. and Israel.

In his speech before the AJC this week, Naftali Bennett, Israel’s minister of diaspora affairs, said the assimilation and potential “loss of millions” of American Jews into mainstream American society fill him with fear because eventually they might not consider themselves part of the Jewish people.

“If there’s one thing that keeps me up at night, it’s not Iran but the future of the Jews in America, and we have to fix this together,” said Bennett, the Orthodox son of American immigrants to Israel.

Jewish continuity and unity were central themes of the AJC’s closing ceremony, which took place in an archaeological park at the southern end of the Western Wall.

Standing next to an Israeli flag and an American flag, Dan Shapiro, an Orthodox Jew and former U.S. ambassador to Israel, cited Korach, the Torah portion Jews will read this Sabbath morning.

Recalling how Korach tried to wrest control of the Israelites from Moses as they made their way from Sinai to Canaan, Shapiro said the biblical villain tried to divide the people.

“Disunity can lead to tragedy,” Shapiro said, referring to the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E., an event the Jewish sages attributed to hatred within the Jewish community.

“Let us reinvigorate our relationship,” he said. “Let us embrace our diversity. Let us express our unconditional love for all our people.”