(RNS) — Quick question: Over the last half-century, how many Jewish books were game changers?

I can think of three.

The first is the greatest American Jewish best-seller in history — “When Bad Things Happen to Good People,” by Harold Kushner. Translated into many foreign languages, Kushner’s book emerged out of the tragic death of his teenage son. It gently called on Jews and others to rethink their assumptions about God. That book was one of American Judaism’s eternal contributions to wisdom literature.

The second is “Standing Again at Sinai: Judaism From a Feminist Perspective,” by Judith Plaskow. Professor Plaskow articulated a Jewish feminist theology and its potential with such power that the book inspired, and even gave birth to, a whole generation of Jewish feminist thinkers.

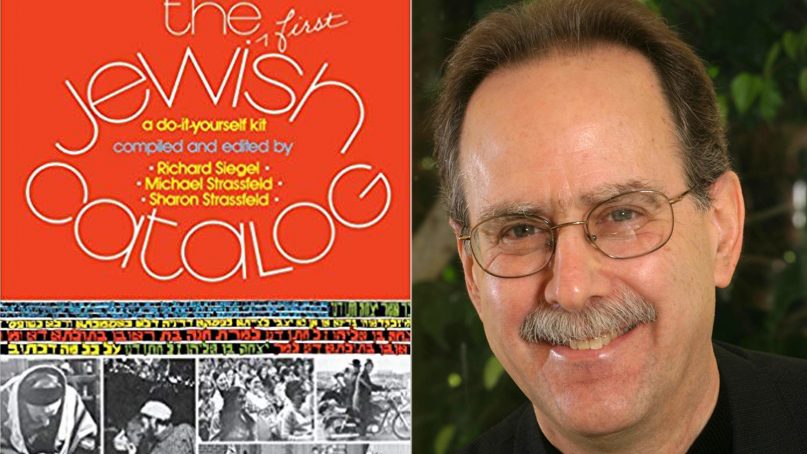

But, in many ways, the book that should really top that list was “The First Jewish Catalog: A Do-It-Yourself Kit,” published by the Jewish Publication Society in 1973 and edited by Richard Siegel and Michael and Sharon Strassfeld.

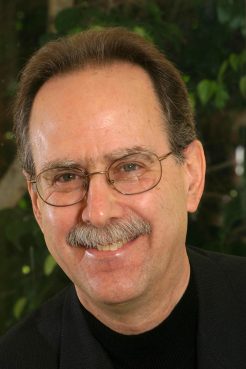

On Sunday (July 15), we said goodbye to Richie Siegel, who died of cancer at the age of 70.

I am bereft — and I know that this is not the first time that I have used such words or such sentiments in this column.

Richie was a Jewish educator, activist and director emeritus of the Zelikow School of Jewish Nonprofit Management at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Los Angeles. He also directed the National Foundation for Jewish Culture (renamed the Foundation for Jewish Culture); created the Jewish Endowment for the Arts and Humanities and married my colleague, Laura Geller, senior rabbi emeritus of Temple Emanuel in Beverly Hills. He was a father, friend, teacher and role model.

And, a visionary. And, a mensch.

Why do I list “The Jewish Catalog” (there would be two more editions) as one of the most important Jewish books of the past half-century?

It’s quite simple. It was not a work of theology. It was, in large measure, the ultimate work of Jewish sociology evolving into practice. It harked back to an earlier era in American Jewry — an era perhaps we are already imitating in our own way.

It was the late 1960s, a time of great social and cultural transformation — the benefits (and failures) of which still touch us today.

Among young Jews, there was the growing sense that synagogues and religious schools had failed to sustain and enrich Jewish life in America. Many of those young activists went to Jewish summer camps. Others became active in college Hillels. Some of them took their Jewish values and put them to work fighting the war in Vietnam. Some of them demanded increased money and recognition from the organized Jewish community.

Out of that Jewish countercultural impulse, the chavurah, or small group fellowship movement, was born. Out of the chavurah movement, the “Jewish Catalog” was born.

Its model was Stewart Brand’s “Whole Earth Catalog.” Its intent was quite simple: For far too long, Judaism and its rituals were in the hands of professionals. But Judaism must belong to everyone. The editors were going to show you how to do it.

That is precisely what they did. The Jewish world was forever changed.

Richard Siegel. Photo courtesy of HUC

Siegel was one of the editors. That was how I first “knew” him and his work. I was in college at the time. The “Jewish Catalog” became my dog-eared, oft-underlined road map of how I was going to create a Jewish life for myself, and for my peers.

But, there was another part of my relationship with Siegel, and it is the part that continues to fuel my imagination. Sometime in the late 1980s, a bunch of us — rabbis, Jewish professionals, one eminent Jewish sociologist (the late, lamented Egon Mayer) gathered one Shabbat afternoon a month at our various homes on Long Island. We were all of the same general ilk, but we were a diverse group — locating ourselves along various places along the spectrum of Jewish thinking and politics.

The agenda was clear: eating, drinking, enjoying each other and discussing and debating the great Jewish issues of the day. The state of Israel and its various challenges were not often on our lips. Instead, our major focus was that which still challenges and emboldens us: How do we make this great tradition sustainable in our time?

You will not be surprised to learn the answer to that question fell into two categories. “It’s all over” and “No, it’s not.” Depending on my mood and the way the bar or bat mitzvah child had done that morning, I vacillated between those two poles.

As for the first option, Siegel would have none of it. He was already waist-deep in his project of supporting and creating a new American Jewish culture. He knew the possibilities. He could see the horizon.

“All over?!?” he said one afternoon, over a glass of merlot and a plate of crackers and brie.

“No way!” he retorted.

“American Judaism is just beginning.”

Those words have always challenged me, inspired me, sometimes haunted me. But what stays with me as I mourn my friend was the absolute determination of his tone. He had no patience with pessimism.

He was far too busy creating the Jewish future.

Right about now, he, Mayer, Alan Mintz and other founders of the Jewish counterculture are having merlot (or better) and brie in the world to come.

They are asking God: “So, is it over?”

God is answering them: “Ask your students and inheritors. Only they will be able to answer that question.”