WOODSTOCK, Ill. (RNS) — “You cannot understand our history as a country until you understand the history of the church.”

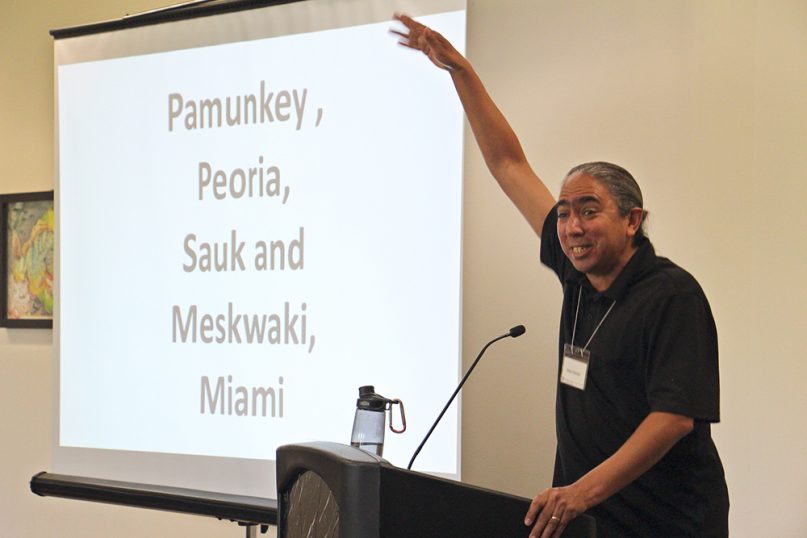

That’s how Mark Charles — a Navajo pastor, speaker and author — began his presentation to a room full of missionaries in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, gathered this summer for their annual meeting.

He was laying out the origins of the Doctrine of Discovery, the idea first expressed in a series of 15th-century papal edicts and, later, royal charters and court rulings, that justifies the discovery and domination by European Christians of lands already inhabited by indigenous peoples.

In recent years, a number of mainline Protestant Christian denominations have passed resolutions repudiating the Doctrine of Discovery. Now they’re considering how to act on those denunciations.

Some are creating educational resources on racism dealing with the doctrine and related themes. Others are calling for “full disclosure” on their denomination’s involvement in land grabs and massacres of Native Americans. Some have even suggested returning church land to the indigenous people who originally lived there.

Like the push to come to terms with racism, the toppling of Confederate monuments and the rise of Christian nationalism, these efforts represent ways the mainline is wrestling with the nation’s original sins.

“I’m encouraged that more and more Christian people seem on board to at least raise awareness,” said Steven T. Newcomb, the Shawnee/Lenape author of “Pagans in the Promised Land: Decoding the Doctrine of Christian Discovery” and co-founder and co-director of the Indigenous Law Institute.

“I think we’re exploring this together in terms of where it can go and the kinds of healing activities that can take place, and the reset of an honor and a respect for the original nations and peoples.”

Doctrine of Discovery

The way Newcomb describes the Doctrine of Discovery these days is “a claim of a right of Christian domination.”

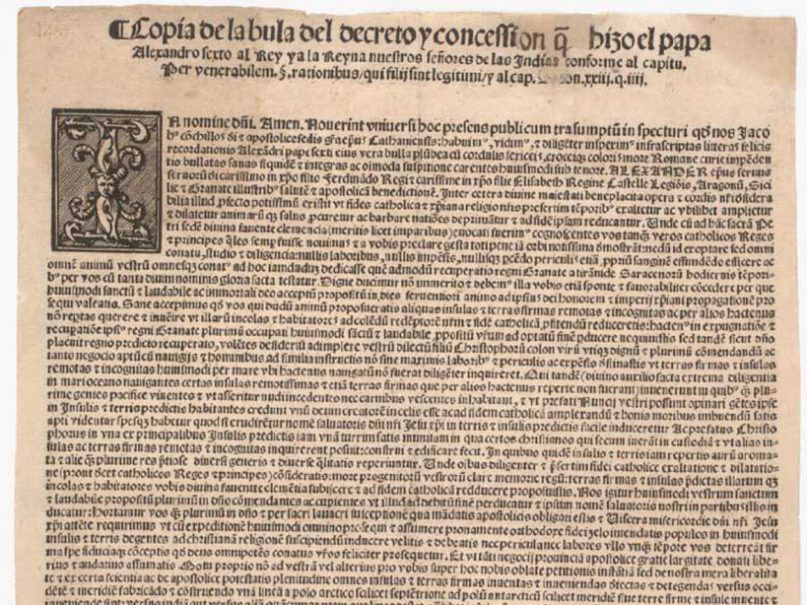

It was first expressed by Pope Nicholas V in the 1452 papal bull “Dum Diversas,” which — along with subsequent bulls “Romanus Pontifex” and “Inter Caetera” — created a theological justification for Christian rulers seizing the property and possessions of non-Christians.

Steven T. Newcomb. Screenshot from video

That doctrine became enshrined in a number of other documents, including the “Requerimiento” read to indigenous peoples in what is now the United States, explaining their land had been donated to Spain and demanding they accept the authority of the pope and of the king and queen.

Protestants didn’t immediately embrace the doctrine, according to Charles. But he hears its echoes in Puritan John Winthrop’s famous “city on a hill” speech. Newcomb recognized it in the 1823 Supreme Court decision Johnson v. M’Intosh, which established that the U.S. government, not Native American nations, determined ownership of property.

It was referenced as recently as 2005 in the Supreme Court ruling Sherrill v. Oneida, in which justices held that the repurchase of traditional tribal lands did not restore tribal sovereignty to that land.

The doctrine, said Newcomb, led to policies like those that took Native American children from their homes to attend boarding schools operated under the motto “kill the Indian, save the man,” causing intergenerational trauma still felt today.

Newcomb has written about presenting Pope Francis with a copy of his book in St. Peter’s Square and meeting with a Vatican official at the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, part of two decades of efforts to get the pope to formally renounce those 15th-century edicts.

Led by the Episcopal Church, Protestant groups slowly have begun to wrestle with the doctrine and are awakening to the need to address its ugly legacy.

Denouncing the doctrine

John Dieffenbacher-Krall, now chair of the Episcopal Diocese of Maine’s Committee on Indian Relations, can’t remember when he first heard about the Doctrine of Discovery. He’s worked for public policy and advocacy groups most of his adult life and volunteered with the Maine Coalition for Tribal Sovereignty since 2002.

But it’s still shocking to him.

On the Sunday after Columbus Day 2006, he asked the rector of his church, St. James’ Episcopal Church in Old Town, Maine, for permission to preach about it, calling on the church, the diocese, the denomination and the entire Anglican Communion to renounce the doctrine.

“As we reconcile ourselves with the indigenous people of the Western Hemisphere, we also do our part in helping to reconcile this broken world with God,” Dieffenbacher-Krall preached that day.

The next year, the Episcopal Diocese of Maine’s convention passed a resolution repudiating the Doctrine of Discovery, and the Episcopal Church adopted a similar resolution denominationwide at its 2009 General Convention.

Pope Alexander VI’s papal bull “Inter Caetera” from 1493. This papal bull gave Spanish explorers the freedom to colonize the Americas and to convert Native peoples to Catholicism. Image courtesy of Library of Congress

A number of mainline Protestant denominations since have approved similar repudiations, including the United Methodist Church, the Unitarian Universalist Association, the United Church of Christ, the Community of Christ, Presbyterian Church (USA), the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and a number of Religious Society of Friends (Quaker) meetings.

The executive committee of the World Council of Churches — which includes 350 churches, denominations and fellowships around the world — also issued a statement repudiating the doctrine and calling on member churches to learn about the history and issues facing indigenous peoples in their areas.

“It’s not that denominations have thought of it, it’s that they’ve been called on by indigenous peoples to live out their faith,” said June L. Lorenzo, who is Laguna Pueblo/Dine and a ruling elder at Laguna United Presbyterian Church, part of the PCUSA.

Lorenzo, was part of the team that wrote a report to the PCUSA following up on its repudiation, detailing how the Presbyterian church played a role in creating and implementing government policies affecting Native Americans; how, because those policies largely were linked to land, the church’s work among Native Americans was, too; and how some Presbyterians throughout history have supported Native Americans’ sovereignty and can model this for the church today.

That report and another resolution expanding the PCUSA’s response to the doctrine both passed this summer. Among the actions they suggest: Each General Assembly meeting should begin with an acknowledgment of the indigenous people on whose land it takes place; the church also will encourage its seminaries to “give voice” to Native American theologies and direct the Presbyterian Mission Agency to create educational resources on racism dealing with the doctrine and related themes.

What’s next?

After a two-hour presentation tracing the impact of the Doctrine of Discovery through U.S. history, Charles asked this summer’s gathering of ELCA missionaries how they felt.

“Convicted,” said one. “Enraged,” “deceived,” “ashamed” and “complicit,” chimed in the others.

“It’s important to acknowledge how this history makes us feel,” said Charles, who is writing a book about the Doctrine of Discovery with North Park University professor Soong-Chan Rah.

Mark Charles — a Navajo pastor, speaker and author — discusses the Doctrine of Discovery with a room of missionaries in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, gathered July 26, 2018, for their annual meeting at the Loyola University Retreat and Ecology Campus in Woodstock, Ill. RNS photo by Emily McFarlan Miller

“There’s a reason we don’t talk about these things. There’s a reason we have a mythology and not a history book. We literally don’t know what to do with this. It drives us crazy.”

A gathering of about 100 religious and indigenous people hosted by the Skä·noñh—Great Law of Peace Center, recently asked that question in Liverpool, N.Y.

“Obviously, a lot of this is merely symbolic,” said Philip P. Arnold, founding director of the center and associate professor and chair of the religion department at Syracuse University.

But, Arnold added: “What would it look like for each of the Christians who attended the New York gathering to return to their home churches and work alongside the indigenous people in their communities?”

More than words

Newcomb said he hasn’t heard many churches seriously discuss returning land to the indigenous peoples to whom it once belonged. But he does remember times non-Native Christians have asked him what they could do to be “allies” to Native Americans.

He told them to go home and have their churches draw up documents acknowledging they are on the territory of the nation originally from that place.

For one Pacific Northwestern church, he remembered, that proved to be a challenge. Members of the congregation had to deal with their fears about what would happen, what it would mean if they acknowledged they were on someone else’s land.

“There was a lot of discussion and dialogue that occurred,” he said. “People had to come to terms with their own psychology and their fears.”

Alongside its repudiation in 2012, the United Methodist Church called for a study providing “full disclosure” of the involvement of prominent Methodists and the denomination as an institution in the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre.

At their next denominational meeting in 2016, United Methodists held a ceremony honoring the descendants of the victims of that massacre. The denomination also released a 173-page report detailing how U.S. troops led by Col. John Milton Chivington, a pastor in the Methodist Episcopal Church, killed 230 Arapaho and Cheyenne people who were peacefully camped along Sand Creek in what was then the Colorado Territory.

This summer, St. John United Methodist Church in Bridgeton, N.J., incorporated elements of Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape and other Native American cultures into its vacation Bible school curriculum, and the denomination’s Oregon-Idaho Conference returned 1.5 acres in Oregon to the Nez Perce nation.

The ELCA’s first test after its denunciation in 2016 came about a month later: There were clashes within the denomination over action to stop the Dakota Access pipeline on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota. Presiding Bishop Elizabeth Eaton later released a statement supporting the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe after visiting the camps where hundreds of Native Americans and supporters had gathered on the reservation.

Now — as the denomination builds its Native American Ministry Fund and plans to observe its repudiation at next year’s Churchwide Assembly — Prairie Rose Seminole, a member of the Three Affiliated Tribes of North Dakota and program director for the ELCA’s American Indian Alaska Native Ministries, said she is seeing hope.

“I’m seeing people willing to put themselves in a space where they’re going to learn other narratives about who we are as a church, and that’s really promising to me because I feel that’s who we are as Lutherans,” Seminole said. “You are living your faith in action when you are questioning the truth around you and finding out what’s missing.”