(RNS) — Indonesia’s President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, a moderate Muslim who enjoys widespread support from the country’s minority religious communities, is resurrecting the country’s founding secular ideology, known as “Pancasila,” as he aims to counter the growing forces of Islamism in the world’s most populous Muslim-majority nation.

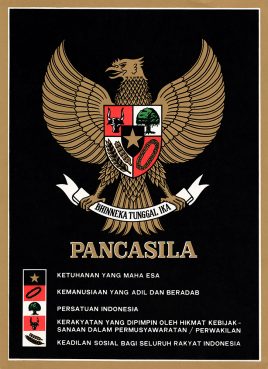

Pancasila, a term from old Javanese that roughly translates as “five precepts,” is a set of principles including “belief in the the One and Only God” and has historically been thought to demand respect for the country’s formally recognized religions – Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Buddhism, Hinduism and Confucianism. Promising a unified Indonesia and social justice for all citizens, it has been considered a key to Indonesia’s relative stability since it gained independence from the Netherlands 73 years ago.

It’s also why, many say, Indonesia has never had an expressly Islamic government.

President Sukarno circa 1949. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Indonesia’s founding president, Sukarno, was Muslim, but his Balinese mother was Hindu, and he led one of the most geographically and ethnically diverse countries in the world. Even before declaring independence, he established the ideology of Pancasila and later integrated its principles into the country’s constitution.

“Sukarno introduced the concept during the debates about the form of the soon-to-be-born Indonesian state,” Robert Elson, a historian of Indonesia, told Religion News Service. “His concern was that Indonesia should not be fractured by divisions over things like ideology, religion or ethnicity.”

Pancasila was also used as a propaganda tool during the three-decades-long reign of Sukarno’s successor, General Suharto. With the advent of democracy in 1999, it fell into disuse, largely due to its association with Suharto’s dictatorial regime.

That changed in April of last year, when Basuki Tjahaja “Ahok” Purnama, the ethnic Chinese governor of Jakarta and a Christian, was defeated in his bid for re-election in a campaign in which Islamic identity played a key role. After his opponent took power, Ahok, a former deputy to Jokowi, was jailed on charges of blaspheming the Quran.

Concerned, the president began to revive Pancasila to counter the threat of Islamic identity politics. June 1, the day Sukarno first stated the principles in 1945, was declared a national holiday. A Pancasila Promotion Group, with members drawn from Indonesia’s Islamic, Buddhist, Hindu and Christian communities, was inaugurated. There was even talk of teaching Pancasila in schools.

A map of the ethnic groups in Indonesia shows the wide diversity the island nation contains. Map courtesy of Creative Commons

In his first Pancasila Day speech, Jokowi encouraged “ulamas, clerics, priests, pastors, Hindu and Buddhist monks, educators, art workers, media professionals, the military and police, and all other elements of society to come together to safeguard Pancasila and our way of life.”

The country’s largest Islamic organization, Nahdlatul Ulama, has also embraced Pancasila, hoping to deter Indonesian Muslims from turning to groups that promote more extreme Islamic ideologies such as the Front Pemuda Islam.

A poster of the Garuda Pancasila, the national emblem of Indonesia, shows the five precepts and the symbol associated with each. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

Pancasila is more than just a rhetorical tool, however. Last July, Jokowi issued a perppu, a government regulation in lieu of law, instructing the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights to disband groups that are anti-Pancasila. So far, it’s been used only to go after far-right Islamic groups, most notably Hizb ut-Tahrir, which was officially banned last year, and was used to justify sentencing the radical cleric Aman Abdurrahman to death in June.

Some worry, however, that defining what is anti-Pancasila is subjective and the concept could be used as it was under the Suharto regime – as a tool to suppress dissent.

Before Suharto’s 1998 fall, said Novan Dwi Andhika with the Global Peace Foundation, “people felt Pancasila was only a political tool for government.”

For now, followers of Indonesia’s minority religions – Christianity, Hinduism and Buddhism – mostly support Jokowi’s efforts to increase awareness of Pancasila. At Buddhist temples in Bandung, Indonesia’s third-largest city, banners were draped calling on all Indonesians to respect the rights of minorities to worship because it was a principle of Pancasila.

Pancasila also allows Jokowi to play both sides ahead of his critically important 2019 presidential race. While he has empowered the national police and government ministries to tackle Islamic extremists, aided by a new anti-terror law, he also made the surprising choice of the head of the Indonesian Muslim Ulama Council, Ma’ruf Amin, as his vice president.

But most Indonesians seem to be willing to believe that elevating Pancasila will help Indonesia negotiate its commitment to be a religious nation with a secular identity.

Attendees stand at the inauguration of President-elect Joko Widodo in Jakarta, Indonesia, on Oct. 20, 2014, under a large Garuda Pancasila statue in the Indonesian Parliament. Photo by Glen Johnson/U.S. State Department/Creative Commons