DURHAM, N.C. (RNS) — Amy Julia Becker always looked forward to the nightly reading routine she shares with her children, especially some of the classic books she loved as a girl — books such as “The Little Princess,” “The Secret Garden,” “Anne of Green Gables,” “Little Women.”

But one day scanning her children’s bookshelf she realized that nearly all the characters in those books were white, like herself, her husband and her three children.

That was the beginning of an awakening for Becker, a Christian writer based in Washington, Conn., who has written a series of books, most prominently “A Good and Perfect Gift: Faith, Expectations, and a Little Girl Named Penny” about her daughter who has Down syndrome.

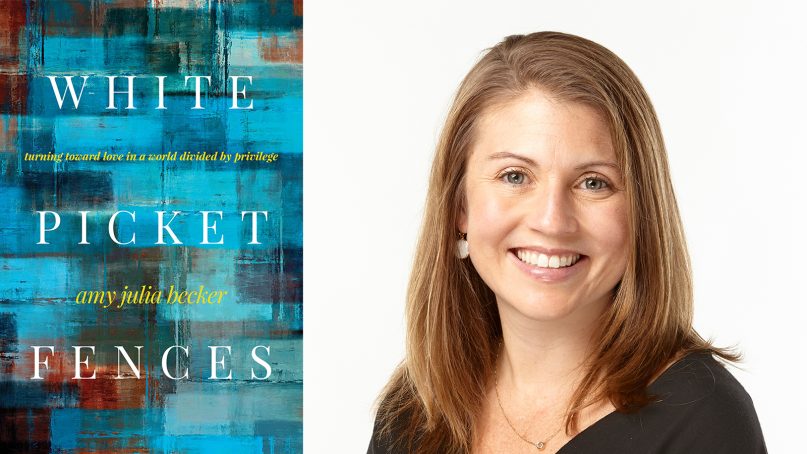

Becker’s latest book, “White Picket Fences” (published by NavPress, in alliance with Tyndale), delves into the hot topic of white privilege and how Becker set about reconsidering her own background as an Anglo-Saxon Protestant, an Ivy-League-educated wife and mother with a growing awareness of poverty, oppression, racial strife and police brutality.

Becker grew up in Edenton, a small town in North Carolina’s Inner Banks region, “within walking distance of the local plantation,” as she writes. In the book she explores what she calls “the lies” she was told about its past. The aim of her book is not to indict, she said, but to give Christians a gentle introduction to the issues.

RNS sat down with Becker during a book tour that brought her to Durham before heading off to Chicago, Richmond, Va., Lexington and Louisville, Ky.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

There have been a bunch of other books written about white privilege. Why did you want to write about it and for whom?

“White Picket Fences” by Amy Julia Becker. Image courtesy of DeChant-Hughes

The books I’ve read by white people talking about privilege have felt like, “I am telling you what you need to learn,” rather than, “I’m telling you what I have learned.” They had a tone of teaching you a lesson rather than telling you a story. I felt many people I knew felt defensive or shamed about the concept of white privilege. I could understand why, but I also thought we really need to be talking about this; is there a way to get over the shame, that actually leads to conversation, and ultimately to transformation, to action and to healing? Feeling you’ve been lectured to … can pretty easily make people retreat, ignore and hide instead of move forward. So that’s the hope — that’s it’s a gentle invitation to a hard conversation, but pointing toward hope at the end.

In the book, you say you awakened to the idea of white privilege while reading books to your children and realizing all the characters were white.

I didn’t set out to read books that only had white characters to my kids. I set out to read books that were classics. The realization was, “Oh, if I have that criteria, it means that I also have this criteria.” It led to thinking more critically about my childhood. That white bookshelf was the lens into seeing things in a more nuanced, complicated way that involved grief.

You grew up in the South. Was it a shock to go through your fourth-grade social studies curriculum and find so few references to African-Americans and to slavery?

I remember loving fourth-grade social studies. I called the school, found out who published the books we used, called the publisher. I was honestly thinking, “I’m pretty sure we didn’t learn any of this. But maybe we just skipped it. Or maybe I didn’t pay attention to it.” So yes, I was shocked. It felt like a caricature of what I thought I might find. I got this textbook. It’s 350 pages. I think there were three veiled references to slavery that were not accurate in some ways and certainly not comprehensive at all. There’s one African-American man featured and he’s giving thanks for his family being transported to North Carolina. So there’s a sense of a white perspective and, really, a dishonest perspective. I felt I was lied to as a child and had not reckoned with something that was really bad.

Now you live in Connecticut in a white, exclusive community. How do you prevent your children from having the same experience?

Author Amy Julia Becker. Photo courtesy of DeChant-Hughes

That’s one of the questions that prompted me to wrestle and ultimately write the book. I could see the ways in which I was perpetuating the same experience. I do think there are opportunities for learning. I found myself shielding my kids from the news, thinking I was protecting their innocence, and was challenged by one of my African-American friends to not do that. That’s been really positive. If I can tell my kids their grandfather died, I can tell them other people are dying, even if it’s for different reasons and for more horrible reasons. So we don’t watch the news but we talk about what’s going on more actively than before.

We have done more in terms of travel — going to the Martin Luther King memorial in Washington, D.C. My husband runs a school and he’s working to have more people of color, not just on campus but also in leadership. We have a guest who’s a person of color stay at our house regularly and he knows our kids and they are getting to know him. We’re not crumbling the edifice of white privilege in any of these things. They are little attempts to name and participate in change. But I think they’re meaningful. Through our church we’re connected to people of a different socioeconomic range, which is pretty broad in our town. All that said, we could move to a city and make some intentional moves that would change our kids’ experiences, but that has not been the choice we’ve made up to this point.

You haven’t made racial reconciliation your mission in life. Does that show others they can take small steps without uprooting their lives?

There are people who have made really dramatic changes and I am grateful for those people and to know them and have their stories in our culture, but for the people who are not going to move or change jobs, what would it mean to take one more step, to look at, “Where do I have influence, right here and right now? Can I push that influence a little bit, so that there are people of color on the board, or my kids are learning something different than if I hadn’t been thinking of this at all?” That’s more where we are. And I think that’s where people are.

You write about the idea of confusing privilege with blessing. Is that a hard lesson for Christians to hear?

It’s very unsettling for many people of faith to think that providence and privilege can be confused. People think, “I’ve worked hard to get what I have,” as opposed to assuming that most people are working hard or want to work hard. Your hard work and someone else’s hard work could land you in a big house in the suburbs and them in poverty. There’s a sense that if you work hard God will reward you. It ignores Job, or God’s scriptural concern for people on the margin, who are never or very infrequently blamed for their position. It’s almost always people in the center who are responsible for that marginalization of orphans and widows and aliens and foreigners.

Did you write the book for the church?

I wrote the book for people who are skeptical of the concept of privilege. As I wrote it, (I encountered) two diametrically opposed audiences: Christians skeptical of the concept of privilege and, on the other hand, a writing group I was in with two women who are secular and Jewish. They were really wrestling with privilege personally and were not so sure about the God stuff. I’d say the primary audience is earnest, thoughtful Christian people who are confused about the concept of privilege. And a secondary audience is people who really care about the concept of privilege but also see hopelessness and despair. They might be interested that there might be some hope, and some love, and some healing.