(RNS) — Two tiny clay seals attributed to King Hezekiah of Judah and an Isaiah who could be the biblical prophet have drawn global notice this year — and raised the visibility of a tiny American church involved in their discovery.

Called bullae, the seals were discovered in a 2009 archaeological dig in Jerusalem under the direction of Eilat Mazar of Hebrew University. The items were found in the same layer of earth within a few yards of each other, suggesting they came from the same time period. It’s also known from biblical accounts that Hezekiah frequently consulted the prophet.

However, it’s not certain the Isaiah seal is that of the prophet: The small clay piece is inscribed “Isaiah nvi,” omitting the Hebrew vowel aleph that would form the word navi, or prophet, according to a report Mazar published in a special issue of Biblical Archaeology Review magazine earlier this year.

Among the assistants processing the area where the seals were found were two students from Herbert W. Armstrong College in Edmond, Okla., operated by the Philadelphia Church of God. The group, which says it has around 5,000 baptized members meeting in congregations around the world, is one of the larger offshoots of the Worldwide Church of God, which was founded by Armstrong but underwent massive schisms after his death in 1986.

Through Jan. 27, the seals are on exhibit at the Philadelphia Church’s headquarters in Edmond, a city of about 95,000 just north of Oklahoma City. The display at the group’s Armstrong Auditorium, the first public exhibition of the seals, has drawn more than 5,000 visitors so far, officials said.

Sherry Beezley, right center, guides visitors during a tour of the Hezekiah and Isaiah seals exhibit at Armstrong Auditorium in Edmond, Okla., on Aug. 9, 2018. Photo by Reese Zoellner

“Both the Hezekiah and the Isaiah bullae are credible, provenanced discoveries,” said Robert R. Cargill, an assistant professor of classics and religious studies at the University of Iowa who also edits Biblical Archaeology Review.

How the items were discovered, and how that discovery was documented, establishes the provenance of the seals. That’s important in archaeology because tracking the discovery of an item helps establish authenticity, explained Brad Macdonald, a Philadelphia Church of God minister who helped arrange the exhibit.

“If an artifact or a bulla isn’t found in controlled archaeological excavations, no one has any idea where that came from,” Macdonald said. “So then they can’t really tell — is it a forgery?”

Cargill said the discovery of the seals ranks about “a 5” in significance on a scale of 1 to 10. While few dispute the existence of either King Hezekiah or the biblical Isaiah, having the seals is a nice touch.

“I Iiken it to having Tom Brady’s autograph,” Cargill said. “Everybody knows Tom Brady exists, but it’s cool to have his autograph.”

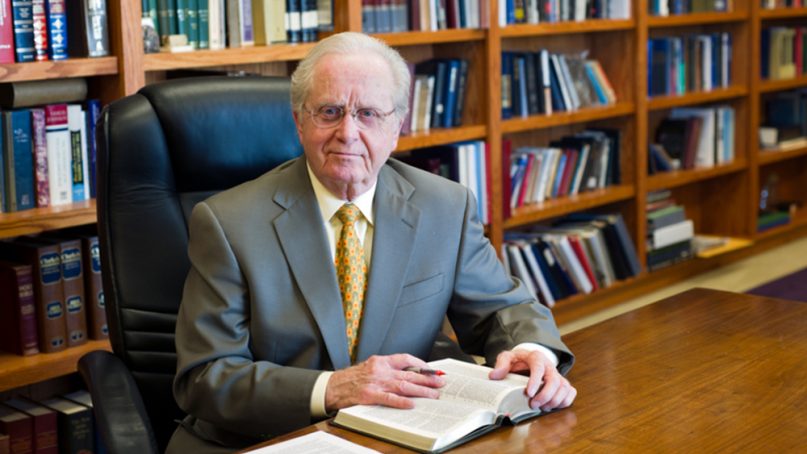

Herbert W. Armstrong died in 1986. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

The seals’ first public display in Oklahoma is drawing attention to both the artifacts and the Philadelphia Church of God, even if the group says such attention was not intentional.

“We’re not saying, ‘Hey look at us,’” Shane Granger, marketing and public relations director for the church’s Armstrong International Cultural Foundation, told Religion News Service.

The attention is a side benefit, he said. “Even the press of Israel asked, ‘What is a world-class exhibit doing in Oklahoma?’ It’s brought Oklahoma and our little work to light. That’s a benefit, not the reason we’re doing it.”

The Philadelphia Church patterns itself after the model established by Herbert W. Armstrong, an advertising man whose business collapsed after a “flash” depression in 1920. Drawing on his marketing and publishing experience, Armstrong built the Worldwide Church into a major player in media evangelism during the 1960s and 1970s. By the time Armstrong died in 1986, membership stood at 100,000 and the group was said to have an annual income surpassing the combined revenues of Oral Roberts’ and Billy Graham’s ministries at the time.

Gerald Flurry, a Worldwide Church minister for 16 years, didn’t support the doctrinal shifts the group initiated after Armstrong’s death and struck out on his own in 1989 after the Worldwide group fired him.

Flurry hews to the doctrines Armstrong promoted: a seventh-day Sabbath, observance of Old Testament dietary laws and feast days, tithing and an approach to prophecy that eschews a “secret rapture” of believers before Christ’s visible return. Instead, Flurry and his followers expect to survive prophesied years of tribulation before the Second Coming.

The group is also unusual for not seeking converts. It actively broadcasts on television, cable networks and the internet, but Granger said the “focus is more on getting the message out, not so much as getting the people in. It’s God’s job to bring people to the church.”

Gerald Flurry, in 2010, leads the Philadelphia Church of God. Photo courtesy of Philadelphia Church of God

Services are not open to the public, he said, so as not to “offend” casual visitors. Instead, those interested must first study the group’s beliefs so they “are fully aware of what they’re getting involved with, what’s expected of them,” Granger noted.

According to David V. Barrett, whose doctoral thesis at the London School of Economics centered on the breakups in the Worldwide Church of God after Armstrong’s death, the Philadelphia group “started more impressively, but they’ve gone downhill ever since.” He estimated initial membership at 7,500 and claimed the group today has perhaps 2,000 committed adherents.

Barrett, whose 2013 book “The Fragmentation of a Sect” expanded on that thesis, says the next issue for the Philadelphia Church will be who succeeds Flurry, who’s 83 years old. “I have no idea what’s going to happen — either his son Stephen or son-in-law Wayne Turgeon will take over.” Both the younger Flurry and Turgeon are PCG ministers.

Granger said the group has no numeric goal for membership growth: “The commission of the church is to proclaim the good news of the coming kingdom of the world and deliver a warning to the world. We’re all trying to prepare for the return of Christ,” he said.