(RNS) — The four saddest words in the English language are “what might have been.…”

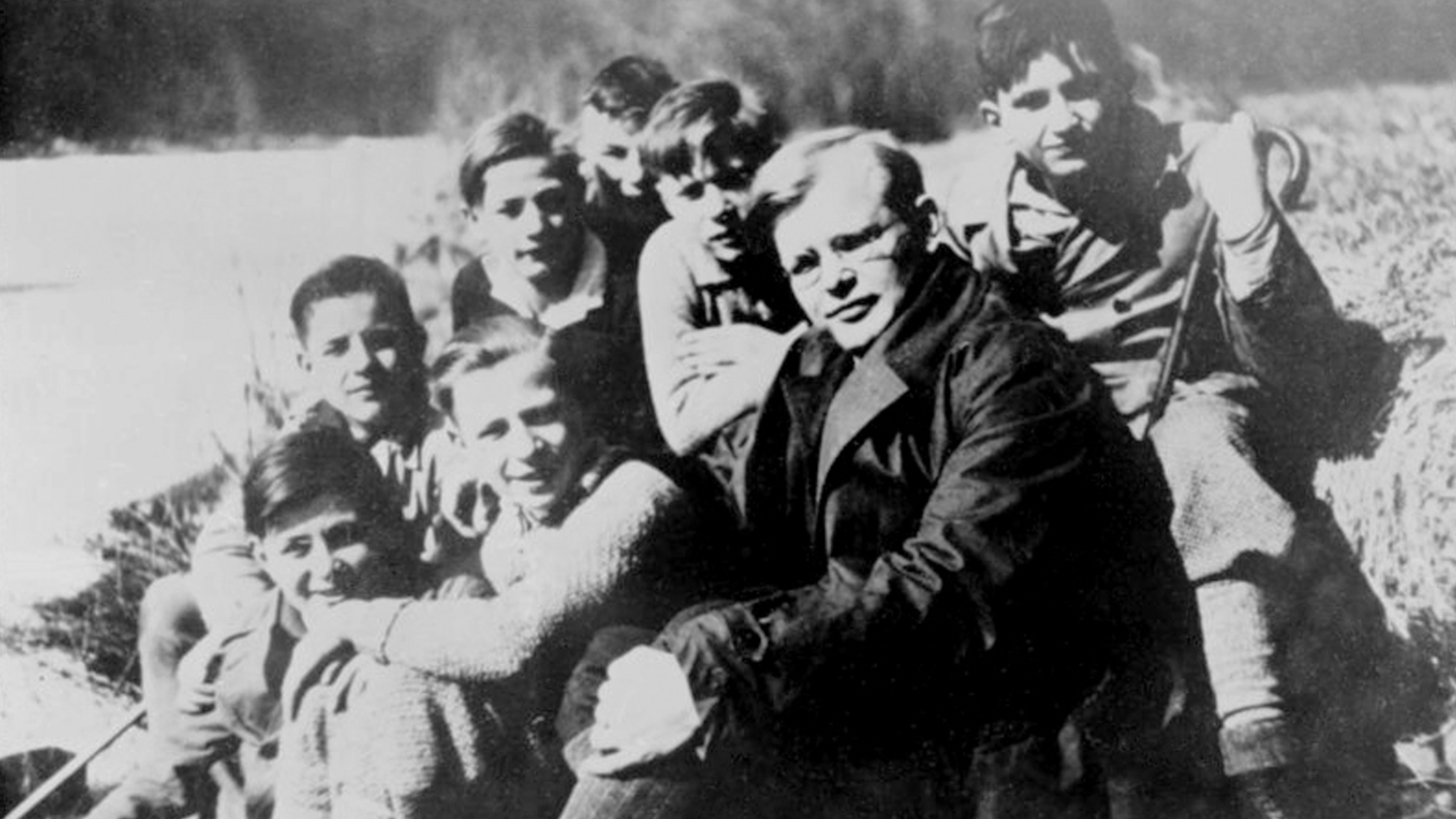

Eighty years ago, as war clouds gathered over Europe, the 33-year-old Christian theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, then a faculty member at Union Theological Seminary in Manhattan, returned to his native Germany after a short stay in the United States.

At the time, Bonhoeffer believed his church’s response to Hitler and Nazism was marked by weakness and cowardice. He saw his country consumed by a monstrous cancer that had devoured nations and had already murdered many hundreds of people on its way to murdering millions.

Frustrated and angered, Bonhoeffer went home to join the political underground movement in Germany. He wrote: “Not in the flight of ideas, but only in action is freedom. Make up your mind and come out into the tempest of living.”

It was a fateful and ultimately lethal decision. Six years later, on April 9, 1945, a month before the end of World War II in Europe, the Nazis executed Bonhoeffer for his opposition to the regime.

Before coming to New York, Bonhoeffer had already been banned by the Gestapo, and in the six years after his final return to Germany, he became the dominant figure of the Protestant resistance. Although more than seven decades have passed since he was hanged for his anti-Nazi “crimes,” there are today numerous articles, books, dramas, poems, operas, songs and films about the young Lutheran pastor who has been called a Protestant saint.

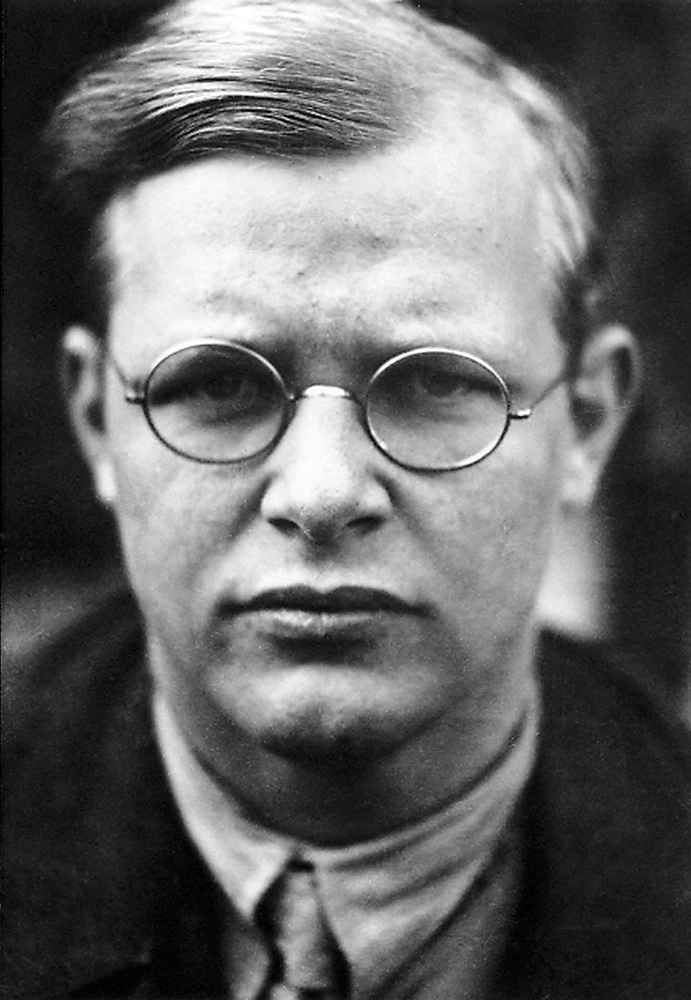

Dietrich Bonhoeffer lived from 1906 to 1945. Photo courtesy Joshua Zajdman/Random House

Earlier, Bonhoeffer had battled the infamous “Deutsche Christen” or “German Christian” movement, which critics derisively called the “Brown Church,” because many of its leaders dressed in brown storm troopers’ uniforms. Its bishops proudly wore swastikas on their ecclesiastical robes and publicly offered the infamous stiff-armed Nazi salute.

The anti-Semitic “Brown Church” completely capitulated to Hitler’s authoritarianism and, as part of its twisted ideology, demanded the elimination of all “Jewish influences” from teaching, liturgy and preaching. Above all, the “Deutsche Christen” movement believed in an Aryan, non-Jewish Jesus.

Bonhoeffer considered the movement a heresy because it abandoned the deep Jewish historical taproots of Christianity and totally surrendered its independence to the anti-Semitic Nazi belief system.

Following the brutal November 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom in Germany and Austria, he made his famous statement: “Only the person who cries out for the Jews may sing Gregorian chants.” Not surprisingly, in the same year, Bonhoeffer told Lutheran seminarians that “Secular freedom, too, is worth dying for.”

As a secret agent and spy of the anti-Nazi underground, Bonhoeffer placed himself in great danger. And as early as 1933, he provided firsthand knowledge of the violent anti-Semitism of the Nazis to Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, then America’s foremost Jewish leader.

After the Gestapo arrested Bonhoeffer in 1943 and until his execution two years later, Bonhoeffer wrote letters from prison that reveal an emerging sense of “Christian realism,” an emphasis on “this world,” an increased appreciation of the Hebrew Scriptures and an original, intriguing concept of “religionless Christianity.”

Bonhoeffer’s letters reveal significant spiritual and personal growth. We can only speculate where his brilliant mind would have led him if his life had not ended so early.

He did what very few of his fellow German clergy did: abandon purely spiritual resistance to Nazism from within the church (sermons, declarations, articles and lectures). Instead, he courageously moved into direct political actions against Hitler and his criminal regime.

But (and it is a very large “but”) there is another side to the Bonhoeffer legacy that needs to be examined: his attitude toward Jews and Judaism.

City University of New York Professor Ruth Zerner, a Roman Catholic, has described that “other” side of Bonhoeffer’s belief system:

“Bonhoeffer’s … observations about Jews and Jewish experiences do include problematic passages, ambiguities, and contradictions. [They] may be only explained by the practical cautions and pernicious exigencies of life in Nazi Germany. I do not intend to suggest that Bonhoeffer was an anti-Semite.

“Rather, like all of us, he was to some extent a victim of his background … Bonhoeffer’s … diagnosis … and prognosis of Jewish historical development are … most disturbing … typical of pre-Holocaust, pre-Vatican II Christian thinking.”

Dietrich Bonhoeffer in an undated image. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Zerner is correct. Bonhoeffer was filled with many “ambiguities” about Jews. He believed they were both a “people loved and punished by God.” Only through baptism could Jews gain salvation, he believed, and he strongly defended the status of converted Jews in the church, even though the baptismal rite meant nothing to Nazis who murdered both faithful Jews and those who had converted to Christianity.

During the early years of Hitler’s rule, Bonhoeffer was more concerned about Nazi efforts to destroy the theological underpinnings and legitimacy of German Protestantism than the vicious physical attacks on Jews that ultimately led to mass murder.

But he did understand that, in his words, “An expulsion of the Jews from the West must necessarily bring with it the expulsion of Christ. For Jesus Christ was a Jew.”

During the 1930s, Bonhoeffer’s theological views on Jews and Judaism evolved as he sought the most effective way to combat Nazism. At a church conference a month before Kristallnacht, he declared, “…instead of talking of the same old questions again and again, we can finally speak of that which truly is pressing on us: what … to say to the question of church and synagogue?”

With that query Bonhoeffer linked Judaism and Christianity as equal partners in relationship with God. Jews are “brothers of Christians” and “children of the covenant.” This was a radical position at a time when so many German Christian leaders attempted to destroy all links between Christianity and Judaism. By 1942 he accurately perceived “a Christendom enmeshed in guilt beyond all measure.”

Victoria Barnett, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s director of Ethics, Religion and the Holocaust and an acknowledged expert on Bonhoeffer, reminds us that in 1939, while still teaching at Union in New York City, he wrote American Protestant leader Reinhold Niebuhr: “I have come to the conclusion that I made a mistake in coming to America … I shall have no right to take part in the restoration of Christian life in Germany after the war unless I share the trials of this time with my people.”

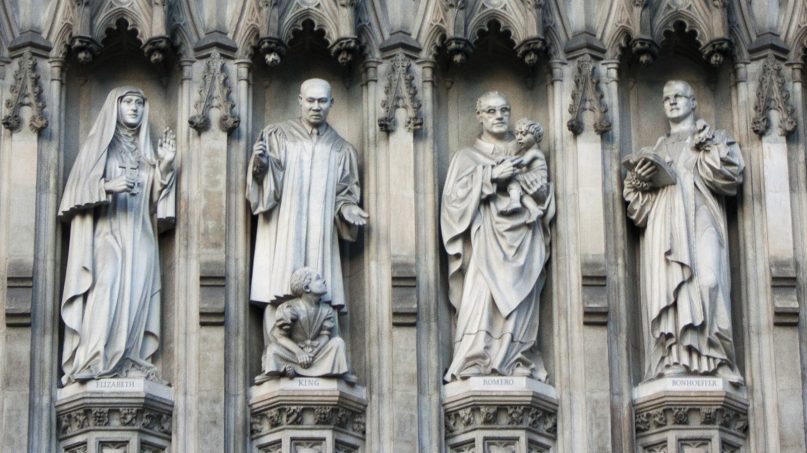

The Gallery of 20th-Century Martyrs at Westminster Abbey includes Mother Elizabeth of Russia, from left, Martin Luther King Jr., Óscar Romero and Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Photo by Zyllan/Creative Commons

I view Dietrich Bonhoeffer as an interreligious pilgrim, a transitional figure.

He expressed many of the negative views of Jews and Judaism that existed in Germany in general and within his church in particular. But as a prisoner of the Nazis and nearing the end of his brief life, Bonhoeffer appeared to transcend many of those hostile teachings and recognize that God wanted him to extend his understanding and compassion toward the Jewish people far beyond the narrow, traditional teachings of his German Protestant Church. However, Bonhoeffer did not live long enough to fully develop his new positive understanding of Jews and Judaism.

As he faced his death on the gallows, less than two weeks after Easter and Passover, he clearly understood that his church had witnessed the mass murders of Jews “…without raising her voice on behalf of the victims and without having found means of hastening to their aid.”

Had he lived, I believe a spiritually transformed Dietrich Bonhoeffer would have become an extraordinary global leader in fostering mutual respect, understanding and knowledge between Christians and Jews.

Ah, “what might have been.…”

(Rabbi A. James Rudin is the American Jewish Committee’s senior interreligious adviser and the author of “Pillar of Fire: A Biography of Rabbi Stephen S. Wise,” published by Texas Tech University Press. He can be reached at jamesrudin.com. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)