(RNS) — Ever since 9/11, Americans have been treated to a host of conflicting, often ill-informed, views about Islam and its deity, Allah.

Some insist Allah is a vengeful being who commands his followers to kill nonbelievers. Others plead that Islam is a religion of peace and its God not different in kind from the one worshipped by Jews and Christians.

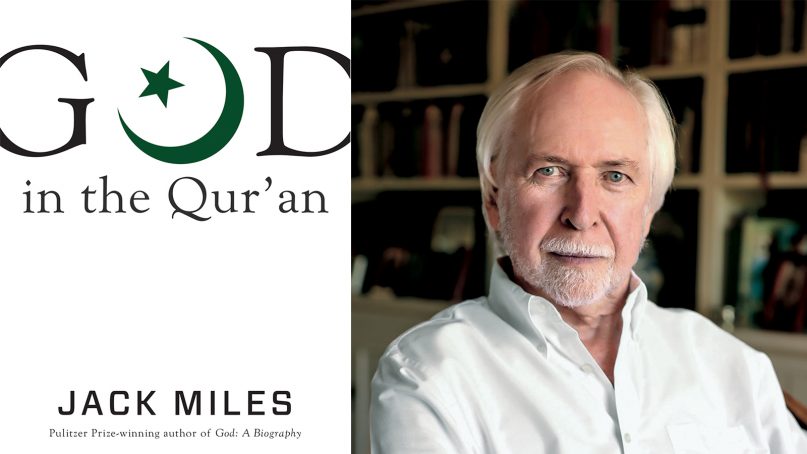

Jack Miles, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning “God: A Biography” and a retired professor of religion at the University of California Irvine, now offers an erudite and highly readable close reading of Allah’s real nature.

In “God in the Qur’an,” he compares the God of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament with God as he is portrayed in the Quran.

Along the way he also compares the stories of Adam and Eve, Noah, Abraham, Joseph, Moses and Jesus, all of whom appear in both the Bible and the Quran.

Miles has long been fascinated with the nature of God in Scripture. Though he himself is Christian and claims limited knowledge of Arabic (he earned his doctorate in Near Eastern languages from Harvard), he is also a trained literary critic and draws on a deep well of biblical and theological knowledge.

Miles, a onetime Jesuit seminarian and a 2002 MacArthur “genius” fellow, now serves as the Corcoran Visiting Chair in Christian-Jewish Relations at Boston College.

The following interview was edited for length and clarity.

What led you to try to tackle the Quran?

I was hesitant at first. I have not made a study of Islam. But finally, I could see a way to do it with my own limitations and that was by studying how the Quran treats signal characters and episodes in the Bible.

The Quran is not narrative. It doesn’t tell all the biblical stories again. It’s not a revised edition of the Bible. It alludes rather than repeats. There’s a distinctly different emphasis. That’s how I found my way into doing this.

Were you interested in correcting the record?

I offer examples of great violence from Jewish and Christian Scriptures and note that we don’t deduce from that that all Jews and Christians are terrorists in waiting. If we don’t do that for ourselves, we shouldn’t do it for Muslims. But that’s a secondary motive, I would say. Once you get that out of the way, you’re free to look at the text, look at the characters and the episodes. That’s a pleasure. It’s a fascination.

What you found is that Allah is more merciful, consistently so, than in the Bible. Is that accurate?

“God in the Qur’an” by Jack Miles. Image courtesy of Penguin Random House

Yes, it is. A friend asked me, what was the biggest surprise you discovered in writing the book? I said, Allah is more merciful than Yahweh. Understand, we’re talking about the same being, but the presentation (in the Quran) stresses not just Allah’s mercy, but also the themes of repentance and forgiveness. I should say, these episodes that involve biblical material probably are no more than a quarter or a fifth of the overall material in the Quran. So, my comment that Allah is more merciful than Yahweh is confined to that portion of the Quran.

I’ll give two examples. Adam and Eve in the Quranic version immediately repent of their sin and throw themselves on the mercy of Allah and Allah forgives them on the spot. They do have to leave paradise, but if they live a good life then at the Last Judgment they will ascend to the heavenly garden. Adam and Eve in the Bible never do repent.

Similarly, the Israelites, just after crossing the Red Sea, create the Golden Calf and God decides to exterminate them as punishment. Moses dissuades him from that, but still there’s horrendous violence imposed on them, a mass slaughter of the lead offenders. In the Quran, the Israelites immediately repent and Allah forgives them. The tablets of the law are not broken. In something approaching efficiency, the Israelites get over it, Allah gets over it and everyone moves on to the Promised Land.

You point out in your book that the biblical idea of humankind created in God’s image doesn’t really exist in the Quran. A lot of interfaith leaders might be surprised to hear that.

Yes, that’s right. Jews pray to “Avinu Malkeinu,” “our Father, our King,” and “Our Father, who art in heaven,” is the beginning of the Lord’s Prayer in Christianity. But there isn’t a similar kind of rhetoric or emphasis in Islam.

Allah is at pains to say that Jesus is not his son, and actually there’s a scene in which Allah and Jesus are speaking and Jesus explicitly repudiates any notion that during his life on earth he ever claimed such as a blasphemous thing. No, he is not the son of God. God had no son, or spouse, and no one really closely associated with him.

This has the effect of making Allah a more awe-inspiring, more august being. Christian theology itself sometimes uses the phrase that God is the “wholly other.” That phrase, “wholly other,” is a pretty apt description of Allah in the Quran.

It appears the theology of the Quran is fairly straightforward in comparison with the Bible. Would you agree?

Yes. I make the point that the Hebrew Bible came into being over a thousand years. The Quran came into being as 20 years of revelation to the Prophet Muhammad from the year 610 to the year 632. So, there is much greater consistency in the portrayal of the character of Allah. He is more moral in a way. He’s more exacting, but always in a predictable manner. Of course, the complexity that Christianity has by having the deity be both divine and human at the same time is also completely absent. So, by being “wholly other” Allah can be wholly simple. That provides a kind of appeal, a kind of fascination, but it isn’t a fascination of complication and conflict.

How would you describe the Quran as a literary work?

In its broadest sense, it’s oratory, and narrowing it a little further, it is preaching. Although a preacher may include an anecdote or allusion to a particular event, the point is always, “How are hearers going to change their lives or go forward in a moral way?” People want that inspiration and correction and direction. Sermons can be great literature. Oratory is a branch of literature and almost a foundational branch. The greatness of the Quran as literature is an oratorical kind of eloquence with music and rhyme built into it.