“The Fall and Expulsion from Garden of Eden” depiction of Adam and Eve in the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

(RNS) — Julia Scheeres always knew she was a sinner.

Raised in Indiana by fundamentalist evangelical parents, Scheeres grew under a moral code defined by obligation and fear.

“God,” she wrote recently, “was a megaphone bleating in my head: ‘You’re bad, you’re bad, you’re bad!’”

When she had kids of her own, Scheeres decided to raise them without the concept of sin, an approach she described recently in a New York Times essay.

After losing her faith, Scheeres says her “notion of sin has evolved.”

She does not fear arbitrary punishment by an invisible God, but rather the ramifications of “real-world concerns”: racism, economic inequality, injustice.

“To me,” she concludes, “the greatest sin of all is failing to be an engaged citizen of the world.”

While Scheeres’ criticism of the Christian concept of sin is fairly simplistic — there are plenty of mainstream contemporary Christian traditions whose paradigms of sin look pretty similar to the one Scheeres has now chosen — she raises a vital question.

Writer Julia Scheeres in 2005. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

What does it mean to be a “sinner” in secular America?

For the 24 percent of Americans who identify as religiously unaffiliated, the deontological approach Scheeres grew up with — a litany of divinely mandated thou-shalt-nots designed to stymie any form of human pleasure — is culturally as well as theologically alien.

What has persisted — as much in the form of our modern conception of the “Protestant work ethic” as in Christian theology proper — is a sense that virtue, and vice, are inextricably linked to self-control.

One of the biggest repositories of sin-related language in secular America, after all, is in the diet and food industries: We talk about sinful desserts, spicy sauces that are hellfire hot.

When it comes to food, clearly, eating for pleasure, for sensation, rather than efficiency qualifies as sin. When food becomes more than fuel — and “virtuous,” organic, sustainable fuel at that — it is the devil’s work.

Even today, contemporary “wellness” culture often makes use of the same dichotomy — albeit cloaked in the pseudo-scientific language of health.

There might not be “good” foods and “bad” foods — linked exclusively to calorie count — but there are still “clean” foods and “dirty ones.” Admitting to dieting may no longer be socially acceptable, but we’re expected nevertheless to crow about our “unprocessed,” “toxin-free” meals and the “cleansed” (and, yes, thinner) bodies that house them.

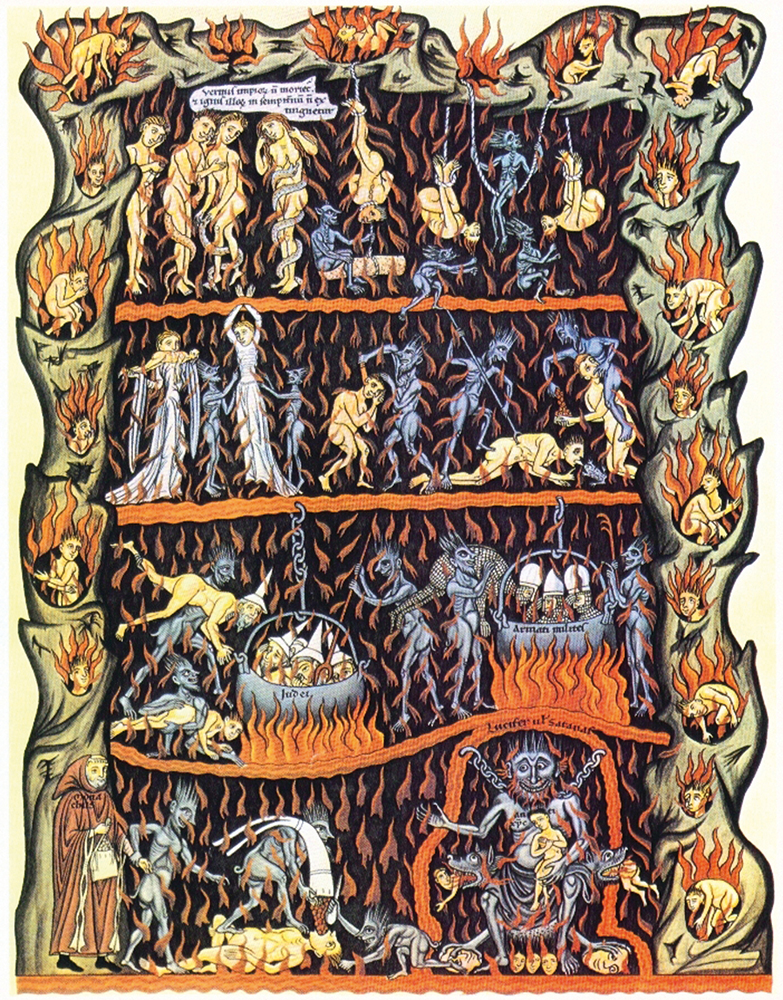

Hell, as illustrated in “Hortus deliciarum.” Image by artist Herrad of Landsberg circa 1180. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

The rhetoric of shame, guilt and filth is still there, but it has been stripped of its spiritual meaning.

All this gives temptation a discomfitingly capitalist, individualistic turn.

Avoiding sin means eating right, exercising and meditating. These are not spiritually enhancing, however; they allow us to be more productive.

Meditation apps don’t promise enlightenment; they offer that “Happier and healthier employees have been shown to be more productive, resilient and creative.” Self-care doubles as maintenance of human capital.

Forgoing chocolate cake for salad becomes not a virtue but simply choosing one feeling — purity — over pleasure.

But our Protestant-infused cultural conception of sin as a lack of individual willpower is starting to change. Both theistic and “secular” American conceptions of sin are becoming more community-focused.

Just look at Scheeres. Her view of sinfulness trades personal piety for social betterment. Her view of sin isn’t just about the individual, but about the individual’s role in the world.

Though her daughter does know what the word “sin” means, Scheeres says her daughter’s moral code is one she “follows not from obligation, but from her own desire to make the world a better place.”

This isn’t an entirely new idea.

St. Augustine’s conception of original sin was not so different from the current secularist idea of a broken world as a challenge, an opportunity to cast off oppression.

If today’s generation has inherited sins like racism and misogyny from the society around us, we still have the chance to change it.

In the words of the Orthodox priest Father Zosima in Dostoevsky’s great theological novel “The Brothers Karamazov,” “we are all responsible to one another for everything”: a responsibility of both hideous weight and of staggering potential.

The early Christians had a term for this sense of responsibility: the creation of the kingdom of heaven on earth.

Ironically, secular ideas about making the world a better place may have more to do with the words of Jesus himself than the conceptions of sin that Scheeres grew up with. Jesus called his disciples to be the “light of the world.”

Now, more and more of us — whatever our faith — are feeling called to do so.