(RNS) – When Yadira Thabatah converted to Islam 13 years ago from Catholicism, she was eager to learn everything she could about her new religion.

The only thing slowing Yadira down was that the 34-year-old mother of four living in Fort Worth, Tex., was born blind. When she and her husband, 33-year-old Nadir Thabatah, who is legally blind but has partial vision, looked for high-quality, English-language resources that she could read, they found nothing.

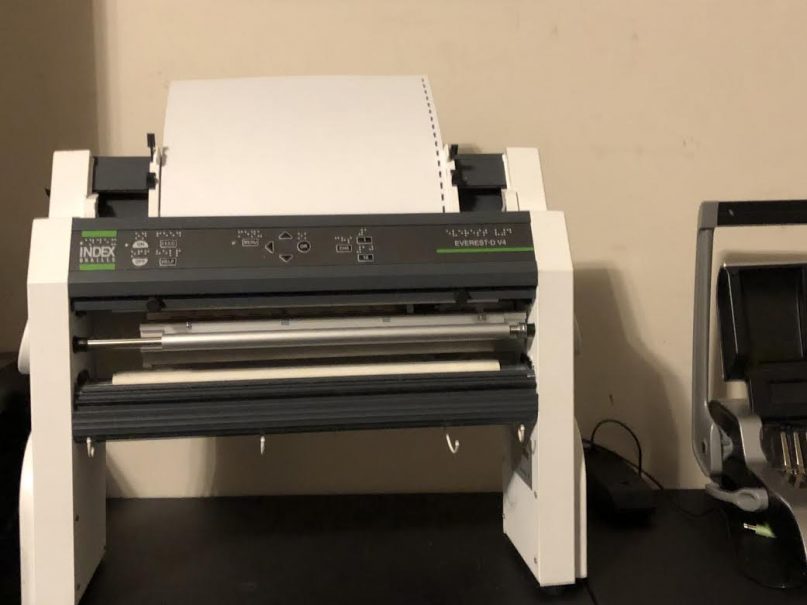

So in 2017, she and Nadir decided it was time for some DIY action. They spent eight months converting a popular English-language translation of Islam’s holy book into braille characters, then used a crowdfunding site to raise money to buy a braille embosser and began producing Quran translations right in their garage.

Yadira Thabatah. Courtesy Islam By Touch

In the past three years, under the auspices of their nonprofit, Islam By Touch, the couple has sent more than 150 braille Qurans to U.S. mosques for distribution to visually impaired Muslims as well as to individuals directly. They have also launched an app to help visually impaired Muslims learn about their faith.

The first time Yadira was able to read the Quran for herself was when she was proofreading her own braille rendering of an English translation.

“I actually cried,” Yadira told Religion News Service. “I’m a reader by nature. Going from being Muslim for about a decade and never having read the Quran, the word of Allah, to actually giving this amazing opportunity to other blind people. I can’t put it into words.”

Other Muslims had recommended audio tapes of Islamic literature over the years, and Yadira did listen to plenty, as well as CDs with translations of the Quran. They got the job done, she said, but she still longed to read the Quran with her own hands.

“How do you expect blind Muslims to have a certain level of faith if they can’t even read their own book?” Nadir asked.

Mahdia Lynn, a disability rights advocate and executive director of inclusive Chicago mosque Masjid Al Rabia, said that many religious organizations consider accessibility to scripture as an afterthought, not considering that it is a matter of “life or death.”

Courtesy Islam By Touch

“We’re talking about entryway into the hereafter, and about having a more fulfilling life here on earth,” Lynn said. “So if as a community leader you fail to make your space accessible to anyone who wants to come in the door, that’s a moral and ethical failing.”

Invented almost 200 years ago in France, braille is a tactile writing system that allows blind and visually impaired people to read and write. Patterns of dots — typically raised on embossed paper, so that they can be read by touch with the fingers — represent letters and symbols in any language.

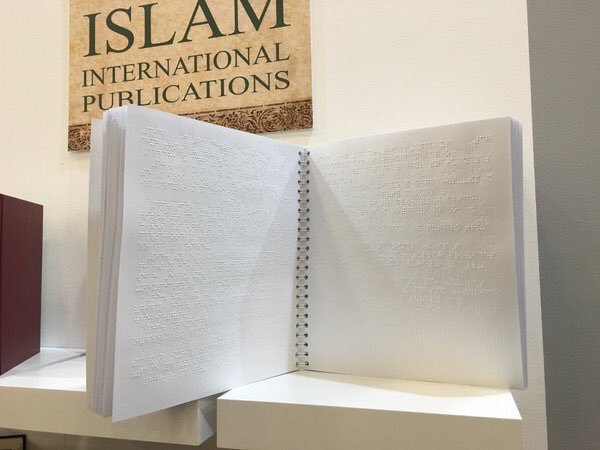

The Quran itself has been available in braille in Arabic since at least the 1980s, when a braille Quran was first published in Turkey. Braille Qurans are now fairly available to Muslims around the world, in part because of the efforts of a blind Turkish man named Selahattin Aydin, who founded the International Union of Braille Quran Services in Istanbul in 2013. Aydin’s group has since helped improve access to braille Qurans around the world.

But braille versions in other languages are harder to come by.

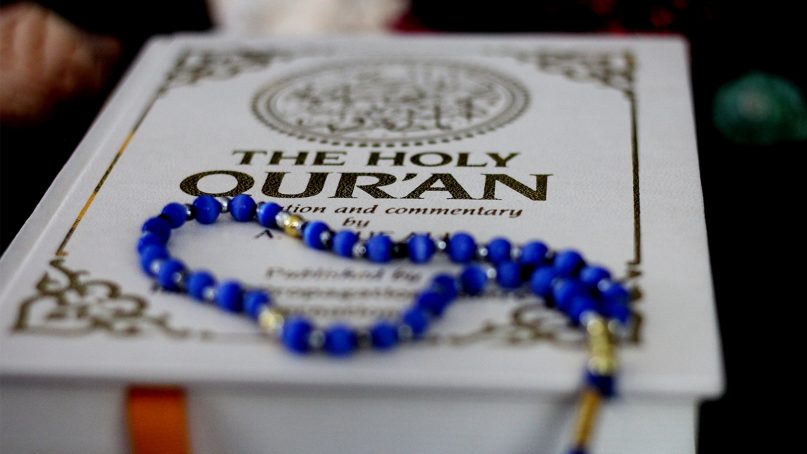

Abdullah Yusuf Ali’s popular English translation is available in a braille version at the Library of Congress. In 2004, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community’s publishing division printed a 12-volume braille rendering of the popular English translation by Maulavi Sher Ali, available for about $100. The Centre for Peace and Spirituality International in New Delhi, India, has also produced a two-volume braille version of Maulana Wahiduddin Khan’s English translation.

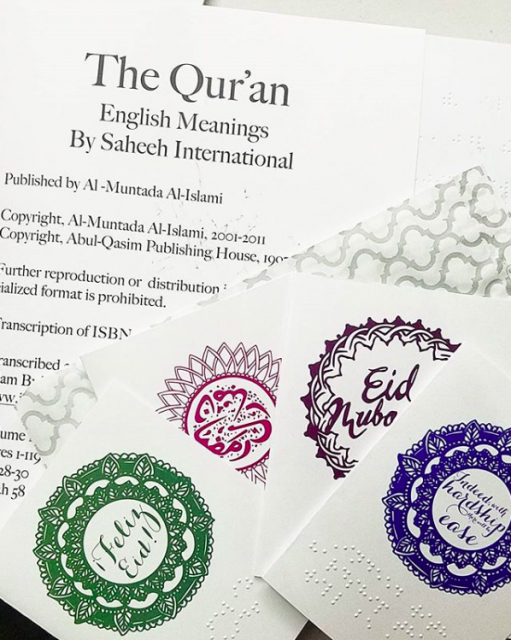

But Islam By Touch claims that existing braille Qurans in English offer inaccurate translations. The Thabatahs chose to transcribe the Sahih International translation — a “reliable” translation, Nadir said — and make copies available to the public for free.

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community’s 12-volume braille rendering of the popular English translation of the Quran by Maulavi Sher Ali. Courtesy Islam International Publication

“I know for a fact there are errors in braille Qurans left and right,” Nadir said, “because the quality control when you send these projects overseas is terrible. So it was important for us to do it ourselves.”

The couple says their version is a major step forward for blind Muslims, who can often be shut out of Islamic communities due to inaccessibility, which feeds insensitivity about their disability.

“This is about removing stigma toward people who are blind,” Yadira said. “This is about equality and justice. Blind Muslims have just as much autonomy and ability to thrive. We are not charity cases, we are not ‘brave’ for simply existing.”

Yadira said she felt traumatized by her experiences in traditional mosques soon after she converted, partially because of patronizing attitudes of other congregants as well as misunderstandings about her guide dog. She has avoided integrating into Muslim spaces since then. When her early search for Islamic literature in braille was frustrated over a decade ago, she initially moved on.

But as their children got older, Yadira decided to homeschool them to teach them about their faith and began looking for resources in braille. In 2016, Nadir had just lost his longtime job in sales. (According to Nadir, his company failed to accommodate his visual impairment when it updated its software, and his sales numbers dropped.)

“So I approached her and said, why don’t we take this step in making Islam a more accessible thing to the blind community?” Nadir said.

The braille embosser used by Nadir and Yadira Thabatah. Courtesy Islam By Touch

Their single 10-volume translation takes about six or seven hours to print and costs around $250 to produce. (To make it transportable, they had to break the book down into several volumes.)

They try to print about two or three Qurans per week, between visiting mosques to deliver talks and sermons, working with advocacy organizations focused on visually impaired people, and preparing braille renderings of other Islamic literature.

Blind Muslims can now access braille Qurans at more than 20 mosques around the country, including at the Bayyinah Institute, a Texas school that offers popular intensive courses on Quranic studies.

The Thabatahs consider that just a start for Islam By Touch. They hope to create accessible spaces for visually impaired Muslims to feel connected both to God and to the rest of the Muslim ummah, or community. According to the 2016 National Health Interview Survey, 25.5 million American adults reported experiencing vision loss, but there are no numbers on that breakdown among faith groups.

“Our low, low estimate is that there are probably about 50,000 blind Muslims in America,” Nadir said. “We want to create a connection between people, so people know that they’re not the only blind Muslim in their community, that there are other people who understand.”