BOSTON (RNS) — For the past 35 years, Roberto Miranda has been fighting Boston’s demons.

Miranda, a Phillips Academy grad with a doctorate from Harvard, is the long-time pastor of Congregación León de Judá, Boston’s largest Spanish-speaking Protestant congregation, which draws 1,000 worshipers on a Sunday.

The church runs a host of social programs to assist immigrants, to battle poverty and ignorance and to help individuals overcome “anything that prevents people from becoming what God intended them to be.”

That can include exorcising demons from a couch in the pastor’s office.

Miranda sees all the church’s ministries as spiritual warfare. Yet he manages to do battle in a way that somehow holds together a high-energy, impactful congregation where undocumented immigrants and Trump supporters praise the Lord side by side even in these polarizing times.

The congregation’s ministries were inspired by a dream he had in the 1990s a few years after Miranda, who had planned to become a professor of Romance languages and literature, took a job as pastor of a fledgling Hispanic congregation of about 60 people.

“I saw this swarm of giant tarantulas settle over the entire skyline of Boston,” Miranda, the 63-year-old senior pastor, told RNS in an interview. “I could see their eyes. They were intelligent. They were evil. Their skin was taut, tight with venom. They just stood there over the city. I knew they were exercising demonic influence. A lot of it was over the financial district.”

Then a lion’s face appeared above all the spiders.

- Director of the youth group Jeannette Ortiz, right, and Eileen Mejia, 14, worship at the youth ministry service at Congregación León de Judá on March 22, 2019, in Boston. RNS photo by Christine Hochkeppel

- Candido Leyba, 21, bows his head in prayer during Senior Pastor Roberto Miranda’s sermon at Congregación León de Judá, on March 22, 2019. RNS photo by Christine Hochkeppel

“He wasn’t roaring, wasn’t angry,” Miranda said. “I knew in the dream, as he looked down on that scene, he was exercising authority — ultimate authority — over what was happening down there. I said three times in Spanish, ‘You are the Lord,’ pointing through the tarantulas to the lion.”

Inspired by that vision, he gave his church a new name (Lion of Judah in English) and moved it from Cambridge to a Boston neighborhood blighted by poverty and crime.

Today, Lion of Judah has become one of Boston’s most influential and enigmatic churches.

Known both for helping undocumented immigrants and for conservative moral teachings on sexuality, Lion of Judah doesn’t fit neatly into any political camp. Instead, it reflects the uniqueness of its Harvard-trained pastor, who emphasizes the importance of humility and routinely confesses to feeling fearful in the ministry trenches.

Ministering in one of America’s least religious cities “excites me, intimidates me, intrigues me,” he told RNS.

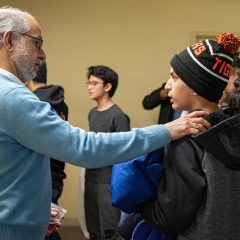

Senior Pastor Roberto Miranda, left, talks with parishioners Jayron Garcia, Maribel Garcia and Javier Garcia, 14, far right, at Congregación León de Judá, on March 22, 2019, in Boston. RNS photo by Christine Hochkeppel

He preached “with huge trepidation” last year, he says, on controversial issues from modern American culture’s sexual fluidity to the need for immigration limits and tight border control.

His “painfully clear” stances made some liberals in the congregation uncomfortable, he said.

“People felt that I had a kind of suicide complex,” he said. “To undertake these issues from the pulpit was kind of dangerous, inflammatory and provoking… But I felt in my heart that I needed for people to know how I thought and how I felt about certain issues.”

But he’s determined not to let his fears stop him, or to keep his congregation from doing great things.

At a Friday night worship event where he exhorted more than 100 teenagers to “never say you’re too young to undertake a great mission in your life, to take yourself seriously or start studying long hours.”

“I’m so honored, blessed and actually a little bit afraid to be here tonight before you,” Miranda said in the introduction to his sermon on Jeremiah’s call. “I know you are a demanding audience. I fear more addressing you than 1,000 adults.”

- Senior Pastor Roberto Miranda, right, holds hands and prays with the youth ministry at Congregación León de Judá, on March 22, 2019. RNS photo by Christine Hochkeppel

- Senior Pastor Roberto Miranda, left, talks with Matthew Acosta, 13, after the youth ministry service at Congregación León de Judá, on March 22, 2019, in Boston. RNS photo by Christine Hochkeppel

- Senior Pastor Roberto Miranda speaks during the youth ministry service at Congregación León de Judá, on March 22, 2019. Photo by Christine Hochkeppel

Children and Family Pastor Jonathan Toledo sings and dances with children during the Awana Club program at Congregación León de Judá, on March 22, 2019, in Boston. RNS photo by Christine Hochkeppel

Miranda describes his church, located in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood, as Pentecostal, evangelical and American Baptist (a mainline Protestant denomination).

The congregation draws people from more than 30 countries and offers ministries in English and Spanish. Each year, professionally staffed outreach programs help more than 1,000 immigrants resolve problems related to legal status and equip more than 500 high schoolers to become successful first-generation college students.

These emphases on immigration and education reflect Miranda’s own background.

Born in the Dominican Republic, he came to the U.S. as a child to join his factory-worker father in New York City. He rode scholarships to Phillips Academy — the same prep school that former President George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush attended — and Princeton University before taking on graduate work at Harvard.

“He is out of the demographic of most Pentecostal pastors,” said Arlene Sanchez-Walsh, an expert on Latino Pentecostalism at Azusa Pacific University in Los Angeles, in an email. “The majority are either self-taught or come from Bible colleges and evangelical seminaries.”

For Miranda, living with complexity is nothing new.

He leads a church that, from the outside, looks nothing like a typical church. It’s a dense, three-building campus resembling a concrete office complex. He leans toward a Republican worldview, he said, yet his church thrives on the edge of Boston’s famously liberal South End. He holds a Ph.D. from a world-renowned university that rejects supernatural explanations, yet he feels called to practice spiritual warfare.

“I have delivered people from demonic powers right where you are sitting,” he tells a reporter seated on a couch in his office. “I have engaged in exorcisms over the years many, many times.

- Senior Pastor Roberto Miranda, left, talks with parishioner Candido Leyba, 21, at Congregación León de Judá, on March 22, 2019. RNS photo by Christine Hochkeppel

- Senior Pastor Roberto Miranda speaks during the youth ministry service at Congregación León de Judá, on March 22, 2019. RNS photo by Christine Hochkeppel

With a slight build and trimmed gray beard, Miranda cuts a grandfatherly figure as he travels elevated walkways connecting CLJ’s buildings. He remembers each person’s preferred language and addresses them accordingly, switching constantly from Spanish to English and back again, using an elbow touch or a reassuring smile to put young and old alike at ease in the leader’s presence.

Miranda’s capacity for straddling Boston’s cultural and political worlds makes the church stand out. The church addresses issues championed by both liberals and conservatives.

Take the hot-button issue of immigration, which hits close to home at CLJ, where about 15 percent of the congregation is undocumented. In June, CLJ will host the first annual, two-day Mygration Christian Conference to reflect on immigration stories in the Bible.

The “My” spelling underscores how “The Bible’s stories are our stories,” according to organizers, including accounts of Biblical migration. Attendees will be led to see immigration through a Biblical lens and discover “God’s heart for the immigrant.”

The church’s ALPHA ministry helps immigrants apply for asylum, prepare for citizenship tests and seek other solutions to immigration problems. ALPHA also mobilizes support for immigrant-friendly legislation, such as a bill that would let non-citizens get Massachusetts driver’s licenses.

Such visible, faith-based advocacy on behalf of immigrants generally comes from mainline Protestant and Jewish congregations, according to Liza Ryan, organizing director of the Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition. She sees CLJ as an outlier, led by Miranda, among Hispanic congregations.

“They’re one of the only (Spanish-speaking churches) that offers to help with people’s immigration paperwork and activate their congregants in the fight for immigrant rights,” Ryan said. “I don’t really know of many other Spanish-speaking or Latino/Hispanic churches that are very active.”

But Miranda also makes sure immigration doesn’t become a partisan rallying cry at CLJ.

A few months ago, he pulled ALPHA staffer Damaris Velasquez aside after she said in worship that being pro-life means “you aren’t going to let children be separated from their parents,” a reference to a Trump administration practice in 2018.

Senior Pastor Roberto Miranda speaks during the youth ministry service at Congregación León de Judá, on March 22, 2019. RNS photo by Christine Hochkeppel

He was concerned with church leaders making partisan statements and offered her some gentle counsel.

“Instead of saying I’m not allowed to give announcements anymore, he said, ‘I’m just concerned about the tone that you were using,’” said Velasquez, an immigrant from Guatemala.

Miranda said Velasquez’s remarks didn’t fit “the diversity of the church.”

He said the political makeup ranges from strongly pro-Trump to anti-Trump, and the church needs to bear witness without stoking unnecessary divisions.

When he was out of the room, another ALPHA staffer explained Miranda’s style, saying that he was kind and encouraging.

“It’s a wise father speaking to his young adult children,” said ALPHA Executive Director Patricia Sobalvarro, who has been part of the congregation since age 11. “We’ve known him for at least 25 or 30 years. He’s never been one to tell us, ‘do this’ or ‘do that.’ His leadership is one of: ‘I’ll watch you from the sidelines as a coach. And if you want my advice, I’ll give you my point of view.’”

Social conservatives also count Miranda as an ally, even though he doesn’t join them in public protests anymore. He chaired the unsuccessful initiative to put legalization of same-sex marriage on the 2008 ballot in Massachusetts. This year, he gave the socially conservative Massachusetts Family Institute a CLJ platform during worship to discuss a youth counseling bill. The MFI warned the bill would curtail parental rights in cases where a child is unsure of his/her sexual identity. Supporters said it would ban so-called conversion therapy.

“When we talk with other pastors about possibly coming to speak at their churches, we’ll send them that video and say: ‘Here we are speaking at Lion of Judah,’” said MFI President Andrew Beckwith. “A lot of pastors get worried that it will be political, (but) this gives us a lot of credibility.”

Miranda’s unusual training helps explain why CLJ has been able to build more infrastructure, staffing and non-profits than other local Hispanic churches with similar passions, according to Rudy Mitchell, senior researcher for the Emmanuel Gospel Center, a ministry support organization in Boston.

“The thing that’s maybe distinctive about Lion of Judah is they’ve developed full-scale social programs,” Mitchell said. “A combination of his spirituality and his education and abilities is attractive, I think, to other people who are well-educated.”

Miranda said he believes God has something else in store for him after CLJ, but he’s still waiting for God to reveal — perhaps in another dream — what the next step is supposed to be.

“I see myself as a soldier, put in a lonely outpost, fulfilling an order and awaiting the next move,” Miranda said. “I’m not sure what it is. But I know it’s out there.”