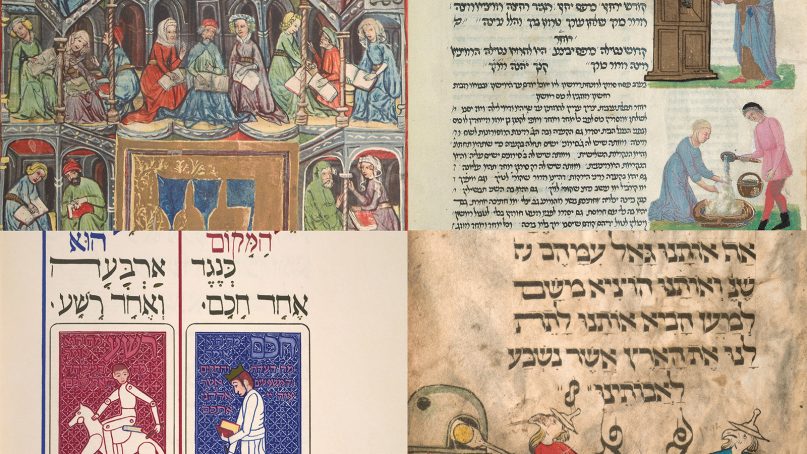

Pages from several rare haggadahs. Photos courtesy of David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University

(RNS) — With Passover and Easter approaching in just a few days, a palpable sense of dread can be felt around the nation. While we love our families dearly, how can we sit at the same table as that obnoxious uncle or unbearable sibling who — fill in the blank — 1) wears a MAGA cap in lieu of a yarmulke, 2) thinks President Trump is the 11th plague, 3) thinks Rep. Ilhan Omar is the devil incarnate or 4) thinks that corruption that is “all about the Benjamins” must be referring to Prime Minister Netanyahu.

Our divisions can sometimes be emphasized at Passover seders, where Jews traditionally tell the story of the Exodus through a simple but profound liturgy called the Haggadah. With over 4,000 versions of the seder narrative available, however, it’s possible to tell the same sacred story from nearly anywhere on the ideological spectrum.

We can choose to look at the Exodus story as a universalist liberation tale, one that would make any newbie socialist proud (“Let all those who are hungry come and eat”). Or it can be a populist revenge tour for all the wrongs brought upon the Jewish people from time immemorial (“Pour out Your wrath upon the nations that did not know You”).

The key is to use the Haggadah as a springboard for civil dialogue. We need to see holidays not as a siege against sense, but one of the few chances that we have to get out from our echo chambers and actually listen to what others are saying.

As we Americans become increasingly exhausted from the constant battling, we become equally desperate for greater unity and clearer moral direction. We seek greater civility, to be sure, but a civility based on principle, not simply an avoidance of controversy. Whether this season you are looking for the promise of an Easter sunrise or the hopefulness of Elijah’s visit that comes as seder is ending, all of us are in need of a boost of optimism.

So how can one be both civil and principled (and presumably chew gum) at the same time?

Women dance during the sisterhood/zhava annual women’s seder at Congregation Beth El of Montgomery County in Bethesda, Md., on March 22, 2015. RNS photo by Sait Serkan Gurbuz

Jews, for ages, have summed up these qualities in one word: mensch.

It is said that Eskimos have 50 words for snow; Yiddish has this one word with more than 50 meanings. Mensch is typically translated into English as “good person.” This is like saying that LeBron James is a “good” basketball player. “Good” only begins to describe it.

A mensch is a human being of any gender, religion or nationality who embodies the following character traits: decency, wisdom, kindness, honesty, trustworthiness, respect, benevolence, compassion and altruism; optimism, curiosity, forgiveness, creativity, gratitude, discipline, enthusiasm, principle, perspective, love of learning, humor, bravery, teamwork, civility, social conscience and perseverance. And then some.

Also, fallibility. You don’t need to be a saint to be a mensch. To be a mensch, in fact, means to be fallible and imperfect, but always striving to do better. To be a mensch means having to say you’re sorry. It means owning failure.

It also means seeking justice but never at the expense of compassion. It means connecting: to family, to one’s people and one’s home; seeking transcendence, seeing the extraordinary in the ordinary, loving unconditionally and living with integrity and humility.

All this from one little cutesy Yiddish word, relegated previously to bar mitzvahs and Jewish funerals.

The term hasn’t yet made it to the level of acceptance of such other Yiddishisms as “chutzpah,” “kvetch,” “schlep,” “bagel” and “oy vey.” Some stylebooks still call for it to be italicized, like other loanwords from other languages. My goal is to bring mensch to full naturalization into the vernacular — for it to become a “thing.”

Because never have we needed it more.

At a family dinner, a mensch is the one who is unconditionally delighted to see everyone at the table, able to see the spark of divinity embedded beneath the crochety surface, and to love that person despite those idiosyncratic – and often incorrect – views. To be a mensch is to approach every conversation from a place of humility.

The seder plate. Photo by Robert Couse-Baker/Creative Commons

No one possesses the entire truth. Yet it is truth that we should be pursuing, and here’s where principle chimes in. We begin with civility and respect, but never yield in matters of fundamental principle, particularly regarding morality and core values.

In the pursuit of truth, the mensch knows to leave the cellphone at the door and resist responding to electronic bait. If you want to allow the dog into the dining room, so be it, but to allow our inner mensch to emerge, crate Alexa for the day, and give Siri some serious R&R.

Without the chance to replenish our Twitter talking points after each course, eventually our social media armor will fall away, and real conversation can begin.

A mensch at this holiday dinner will arrive filled with an attitude of gratitude, simply glad to reach another family celebration. Jews call these “Shehechiyanu moments,” named after the prayer recited to thank God for sustaining our lives, renewing our spirits and enabling us to mark this sacred arrival.

A Shehechiyanu moment is akin to what we used to call a Kodak moment. When we snap a photo, we are trying to freeze an instant of sublime happiness in time, so that we can retrieve it when we need to reconnect to our truest selves. The Shehechiyanu blessing, like a photo, captures those priceless moments, but also connects each moment to the bigger picture. It links all the pictures together in the album, and every album to the eternal web of life.

Once we embrace civility with principle and combine it with mutual respect and a deep appreciation for one more year of simply being together, we can allow other menschlike qualities to emerge, and together we can forge a better world.

So over the upcoming holidays, let’s all pledge to become honorable menschen.

(Rabbi Joshua Hammerman is the spiritual leader of Temple Beth-El in Stamford, Conn., and author of the recently published “Mensch-Marks: Life Lessons of a Human Rabbi.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service.)