(The Conversation) — In recent weeks, Democratic presidential hopeful Pete Buttigieg has captured wide media attention.

One reason is that Buttigieg is the first openly gay presidential candidate. Another is that he has been unguarded in speaking about his religious beliefs, arguing that his faith shapes his politics.

In a recent interview, Buttigieg said that “Christian faith” can lead one “in a progressive direction.” He has also argued that Christianity teaches “skepticism of the wealthy and the powerful and the established” while elsewhere expressing concern that in the U.S. “concentrated wealth has begun to turn into concentrated power.”

These arguments are all the more striking since Buttigieg is from Indiana. According to a 2014 Pew survey, twice as many of the state’s voters identify as conservative than as liberal. Moreover, self-identified conservatives significantly outnumber liberals among Indiana Christians. It might seem that Buttigieg’s convictions are at odds with the beliefs of many people in his state.

A century ago, however, views such as Buttigieg’s flourished in the Midwest.

A progressive religious movement

As a historian of U.S. religion, I have studied the vibrant period for religious liberalism in the early 1900s. Indiana and nearby Midwestern states were at the center of a movement – the Social Gospel movement – that linked Christianity with progressive politics.

The movement gained wide popularity in American Protestantism at the beginning of the 20th century. Its proponents proclaimed the need to improve the world rather than focusing on being saved in the next life, which was the common message espoused in most U.S. churches.

One exemplar of the Midwestern roots of the Social Gospel was the Methodist clergyman Francis J. McConnell, who became known as an advocate for progressive policies.

McConnell grew up in a small-town in Ohio before attending Ohio Wesleyan University. From 1909 to 1912, he served as president of DePauw University in central Indiana.

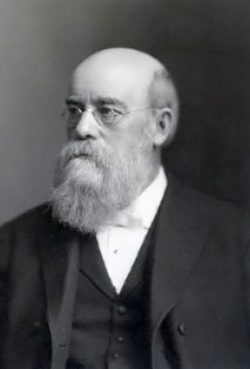

Washington Gladden. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

While there, he published a book that made arguments similar to Buttigieg’s belief that faith should inspire social action. McConnell insisted, “The moral impulse calls for the betterment of all the conditions of human living.”

There were other prominent Social Gospel proponents who lived and worked across the Midwest at the time. From his Columbus, Ohio, church, Washington Gladden became famous for urging greater protection for workers and the poor. Further west, in Kansas, the minister Charles Sheldon published the book, “In His Steps,” in 1896. It urged Christians to improve the lives of those around them.Historian Susan Curtis writes that McConnell “participated in the promotion of an evolving welfare state.”

A religious challenge to big business

It wasn’t just the presence of these leaders in the region – more important was the resonance of the message of the Social Gospel there. Small cities and towns in the Midwest were the heartland of the Social Gospel.

The Social Gospel’s critique of big business resonated in communities throughout the Midwest.

The movement emerged in response to the development of massive national corporations in the late 19th century. These companies consolidated wealth and power in large cities, often quite distant from Midwestern communities.

Demands for a social safety net for workers were rising in places like Columbus and Indianapolis as much as in larger metropolises like New York or Philadelphia.

These leaders urged the creation of a social safety net to provide a “living wage” for all workers. They also advocated increased government oversight of corporations, which they believed had grown too large. At a time when many churches supported big business, this was a counter-cultural position.

Lecturing back in his home state of Ohio in 1912, McConnell likened modern “corporate kings” to the absolute monarchs of previous centuries. Similar to rulers of earlier times, corporate titans exerted great power at a distance and could inflict harm.

McConnell believed organized Christianity could inspire people to challenge big business. “Corporations thrive best morally when they enjoy the full light of publicity,” he wrote.

Like Buttigieg, who argues that his Christian belief makes him skeptical of the effects of concentrated wealth, these Midwesterners saw Christianity as the antidote to distant corporate power.

New life for an old message

South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg laughs before he speaks to a crowd about his presidential run during the Democratic monthly breakfast at the Circle of Friends Community Center in Greenville, S.C. on March 23, 2019. Buttigieg was the longest of long shots when he announced a presidential exploratory committee in January. But now the underdog bid is gaining momentum, and Buttigieg can feel it. (AP Photo/Richard Shiro)

Over the last few years, observers have noted the resurgence of a religious left inspired by the ideals of the Social Gospel.

With Pete Buttigieg, the religious left has its most prominent political leader to date – and from the part of the country that was historically important for its emergence.![]()

(David Mislin is assistant professor of intellectual heritage at Temple University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service.)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.