(RNS) — In early June, Sikhs around the world gather to commemorate one of the more painful moments of their recent history. On June 1, 1984, the Indian army launched a military assault on Darbar Sahib (Golden Temple) in Amritsar, in northern India, the most historically significant gurdwara, as Sikhs call their places of worship, and the epicenter of the Sikh psyche.

The timing of the attack coincided with the days when Sikhs around the globe commemorate the execution and martyrdom of their fifth guru, Guru Arjan Sahib, the architect of the historic Darbar Sahib. For centuries Sikhs have flocked to this site in Amritsar every June to honor his memory and contributions.

In 1984, Sikhs inside the complex were paying their respects when Indian military forces arrived and placed them under siege. A deliberate and calculated massacre ensued over the next eight days, perpetrated by a government against its own citizens. By its end, thousands of innocent Sikhs would be dead — devotees who had come to honor their guru who would now never return home.

At the time, many saw the military attack, which the Indian army referred to as Operation Bluestar, as the climax of tensions that had been building for decades. Since the establishment of the Indian nation in 1947, Punjabis had felt aggrieved by what they considered unequal treatment from the federal government, and their protests increased significantly in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

In the words of scholar Cynthia Keppley Mahmood, “The only possible reason for this appalling level of state force against its own citizens must be that the attempt was not merely to ‘flush out,’ as they say, a handful of militants, but to destroy the fulcrum of a possible mass resistance against the state.”

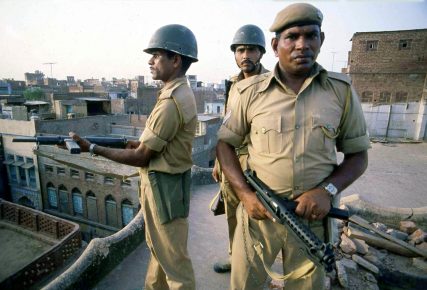

Indian troops take up positions on rooftops around the Golden Temple, in Amritsar, on June 6, 1984, after soldiers started to move into the complex. (AP Photo/Sondeep Shanker)

Government officials and state-run media justified the attacks as counterterrorism, but several factors suggest that the military assault of 1984 was more akin to ethnic cleansing: its execution during a pilgrimage week, the tens of thousands of innocent civilians killed by the police, the long and careful planning that went into the operation, the volume of extrajudicial mass killings of Sikhs that were to come later in 1984 and throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. When the assault is placed in historical context, it is hard to view it as anything less than a crime against humanity.

Anthropologist Joyce Pettigrew explains the purpose of the invasion: “The Army went into Darbar Sahib not to eliminate a political figure or a political movement but to suppress the culture of a people, to attack their heart, to strike a blow at their spirit and self-confidence.”

As we remember the anti-Sikh violence of 1984 decades later, it’s troubling to see how much resonance it has in our world today. Refugees fleeing genocidal violence in Myanmar. White supremacist hate raging violently across North America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand. Millions of Uighur Muslims in concentration camps across China.

We are witnessing a sobering and unprecedented rise of ethno-nationalism all around the world. Ethno-nationalism, in a nutshell, is an exclusivist vision for creating a society, usually based on a perception of shared traits, such as race, language or religion.

In this Aug. 23, 2018, photo, Bangladesh military personnel check vehicles for Rohingya refugees on the road that connects refugee camps to the nearby tourist town of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. More than 700,000 Rohingya Muslims fled waves of attacks by Myanmar security forces and crossed the border into Bangladesh nearly a year ago. Despite months of discussions among Myanmar, Bangladesh, the United Nations and a string of aid agences, there are few signs that the Rohingya can go home anytime soon. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

It is generally perceived as a regressive way of constructing and inhabiting a nation, yet its popularity is surging in the skyrocketing Hindu nationalism in India, or the rise of white nationalism in the United States.

Ethno-nationalism stands opposed to a form known as civic nationalism or liberal nationalism, which is espoused by modern democratic models such as the United States or Canada. Civic nationalism is not so concerned with how we look or where we come from, but instead, constructs identity on the basis of shared values, such as equality, human rights, freedom and inclusion.

My sense is that most of us would agree that this civic nationalism offers a more progressive way of forming a society, one that better reflects the type of world we want for ourselves and our children.

Yet, here we are. The global trend toward ethno-nationalism is leading to increased marginalization and alienation, leading to surges in hate groups and hate violence, and leading to a rise in genocidal violence all over the world, from the United States and Saudi Arabia to Poland, Brazil and Christchurch, New Zealand.

As a historian and activist, I’m concerned. As someone whose family has been on the direct receiving end of bigotry and hate, I’m concerned. As someone who feels the pain of the anti-Sikh violence of 1984, I’m concerned.

So what can we do?

One thing I have learned from the trauma of 1984 is the importance of acknowledgment in the face of persecution. Sometimes, the most powerful thing you can do for someone who is enduring suffering is to affirm them. Let them know you see them. Let them know you care.

One of the more painful aspects for me as a Sikh has been the constant erasure and denial of the state’s complicity in the attacks of 1984. Rather than owning it and apologizing, or even simply acknowledging that it was wrong, the Indian state has continuously doubled down on its actions — as if anything could justify playing a role in massacres of genocidal proportions.

Because the Indian government has not held itself accountable — and, instead, used the divisive narratives to further discord in modern Indian politics — I along with many of my Sikh friends have found it harder to find closure and to move on. As the saying goes, no justice, no peace.

With this experience in my own heart, one important takeaway for me comes in the power of witness. Sometimes, simply being present with someone can be a form of allyship. In a moment when someone feels most dehumanized and, therefore, most isolated and most vulnerable, a simple acknowledgment can show them that their humanity is still valued.

I try to apply this in my own life by showing up for other people and communities in their moments of need. And I have found that it actually helps with my own healing as well. When we begin showing up for others, they tend to reciprocate, wanting to do the same for us.

Sometimes, it’s just a matter of someone taking the first step. Why shouldn’t that be you?