This story is part of a Religion News Service series on slavery and religion published as Americans commemorate the 400th anniversary of the forced arrival of enslaved Africans in Virginia. The rest of the series can be found here.

MONTGOMERY, Ala. (RNS) — Connections between Christianity, Confederacy and civil rights — and the history of slavery — are in plain sight here in Alabama’s capital.

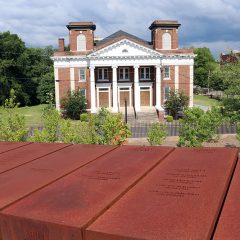

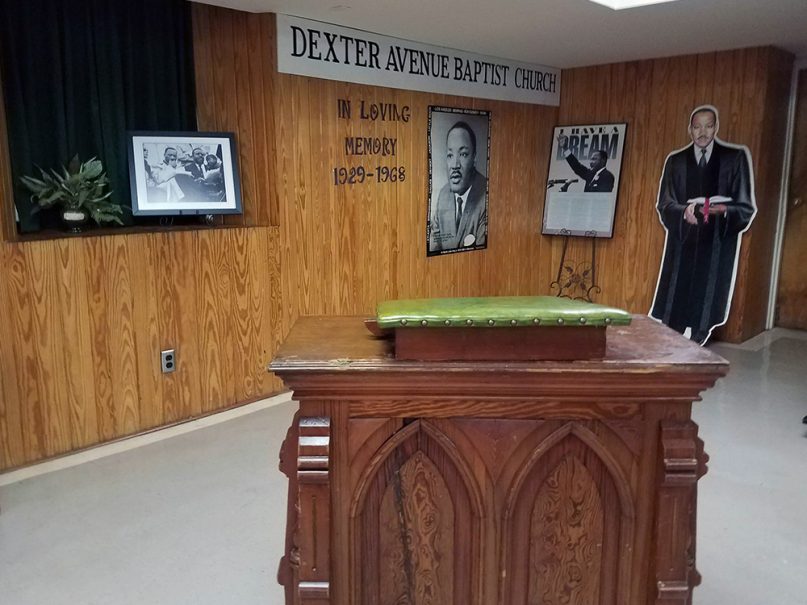

Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church is known for its most famous pastor, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., but one of its early locations was once a slave pen.

St. John’s Episcopal Church, where Confederacy President Jefferson Davis worshipped, is across the street from the building where Rosa Parks was tried after she refused to give up her bus seat to a white man.

- Old Ship African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church across from the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

- St. John’s Episcopal Church, where Confederacy President Jefferson Davis worshipped, in Montgomery, Ala. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

And just beyond downtown, Old Ship African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, a congregation that dates to before the end of slavery, sits across the street from the memorial that opened in 2018 to remember more than 4,400 lynching victims.

As the nation marks the 400th anniversary of the forced arrival of Africans in Virginia — and Alabama has its bicentennial — a walk through Montgomery’s streets reveals the legacy of slavery in America.

Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church is where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. preached in Montgomery, Ala. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

“It is the cradle of the Confederacy and the birthplace of the modern civil rights movement,” said Kathy Dunn Jackson, volunteer historian of Old Ship AME Zion Church.

Religion sometimes played a role in the violence that followed slavery, as seen at the Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

Amid the 800 6-foot orangey-brown steel columns memorializing those lynched from 1877 to 1950 — often by white Southerners angered by the end of slavery — is an example of a religious ceremony being cited as a reason to kill.

Columns memorializing lynching victims are suspended above visitors at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

“Arthur St. Clair, a minister, was lynched in Hernando County, Florida, in 1877 for performing the wedding of a black man and white woman,” reads a sign.

The memorial, on a 6-acre site, is described by its creators as “a sacred space for truth-telling and reflection about racial terrorism and its legacy.”

RELATED: Angela, a First African, tells her story in Jamestown, but her faith is a mystery

About a mile away, the EJI’s Legacy Museum, which traces history “from enslavement to mass incarceration,” features holograms of black men, women and children, held in pens singing spirituals like “Lord, How Come Me Here?” and speaking of missed loved ones from whom they have just been taken.

Soil from lynching sites fills jars at the Equal Justice Initiative’s Peace and Justice Memorial Center in Montgomery, Ala. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

Like Dexter Avenue’s early location, the site of the museum was once a slave pen: “You are standing on a site where enslaved people were warehoused,” read words on a wall at its entrance.

Another sign points out that in 1860 Montgomery, there were more places for trading slaves than hotels and churches.

The current site of the Montgomery church where King pastored was purchased for $270 in

1879, and that spot also has ties to slavery — specifically the heart of the Confederacy in 1861.

The Alabama Capitol is blocks away from several famous churches in Montgomery. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

“It’s one block from the state Capitol,” said Montgomery historian Richard Bailey. “Jefferson Davis was inaugurated within sights of what became that church.”

At the time of Davis’ inauguration, slaves made up almost half (45%) of the state’s population, or 435,080 people, according to the Encyclopedia of Alabama.

Steve Murray, director of the Alabama Department of Archives & History, said the Capitol steps and that nearby church continued to be at the vanguard of major events a century after the start of the Civil War.

- Visitors tour the Dexter Parsonage Museum, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. lived between 1954 and 1960, on June 8, 2019, in Montgomery, Ala. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

- Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church, right, is just a block from the Alabama Capitol, left, in Montgomery, Ala. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

“At the bottom of those steps is where the Selma to Montgomery march culminated,” he said. “You pack an awful lot of really significant American history into a few square blocks.”

A half a century later, tour director Wanda Howard Battle pointed out the lectern in the red brick church’s basement that was placed on a tractor-trailer flatbed for King’s speech when then-Gov. George Wallace would not allow the civil rights leader to speak on the Capitol steps.

RELATED: From New York to Alabama, blacks worshipped in own spaces before slavery’s end

Over the last 200 years, there has been a transformation on the street that changed from Market Street to Dexter Avenue and from slave markets to other kinds of commercial business.

The first pastor of the church that has been on one corner for most of that timespan was born a slave. The middle-class blacks who created the Second Colored Baptist Church changed its name twice, first to the street’s new name and then to honor King. Two blocks west, in an area where slaves were once confined, a fountain flows and signs recognize “outstanding Alabamans,” including King.

This lectern, in the basement of Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church, was used by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. when he spoke at the conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery March at the nearby Alabama Capitol in Montgomery, Ala. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

Curtis Evans, a historian of American religions at University of Chicago Divinity School, said the city’s changes are particularly striking because slave owners may have originally hoped to use Christianity as a “form of social control” but a century later many black clergy became active in the civil rights movement.

“What happened, ironically, is that many enslaved people adapted Christianity to their own circumstances and used it as a very different form of imagining justice in the United States,” he said, “compared to, for example, white evangelical Protestants who have such different views about the role of government and political issues.”

While historians call the overall change pivotal, Battle, a member of an AME Zion church, prefers to consider it providential.

“I just see it as God moving everybody into place,” she said.