KOCHI, India (RNS) — Two thousand years ago, the first Jewish residents in this city could feel the Arabian Sea breeze as they left one of Kochi’s two synagogues in the Mattancherry district, or as the 18th-century British coined it, “Jew Town.”

The neighborhood, where today warehouse workers can be seen bending over mounds of black pepper, ranks alongside Jerusalem as a community with a long history of Jewish life.

But where a community once built schools and homes, kosher restaurants and shops, most of the streets are lined now with Muslim or Hindu souvenir vendors and eateries. One synagogue is now rubble, covered only by a curtain. The other is hidden inside an aquarium store.

A newer synagogue, not yet 500 years old, is the only one that regularly holds services. The Paradesi Synagogue serves as a major Jewish tourist attraction.

- The Paradesi Synagogue serves 24 local Jews in Kochi, India. Photo by Aaron Schrank

- A sign marks the entrance to historical Jew Town, within the wider Mattancherry district, in Kochi, India. Photo by Aaron Schrank

The Jews in this region of Kerala go by different names: Paradesi, Malabari, Baghdadi, Cochin, Indian. But time is quietly claiming this ancient community. Even centuries of disputes between the Jews who arrived in the first century and Spanish and Portuguese Jews who arrived in the 1500s didn’t cause the population to dip. Now, interfaith marriage and migration to Israel may soon end it.

These days, the community attracts mostly tourists from around the world, people eager to shake the hands, walk in the footsteps and pray in the synagogue of the city’s 24 remaining Jews.

Sarah Cohen, 96, sits in her home, which doubles as her embroidery shop, with the Torah in her lap. She mostly dozes, her bespectacled eyes just grazing over the Hebrew words.

Thaha Ibrahim, left, speaks with tourists meeting Sarah Cohen, the oldest Jew living in Kochi, India. Cohen, 96, is often a stop for Jewish tourists visiting the area. Photo courtesy of Aaron Schrank

“Sarah aunty,” said Thaha Ibrahim, a longtime family friend who cares for Cohen and has become something of an expert on the Jewish community. It’s unclear how aware Cohen is of her surroundings, or if she understood why Ibrahim and a dozen excited Israeli tourists roused her to say hello.

Cohen’s home and embroidery shop have become popular stops for Jewish tourists. They’re eager to meet the last of a generation of Cohens who immigrated to Kochi with other Paradesi Jews in the 1500s.

But the Paradesi — or “foreign” — Jews weren’t the first to move to India. In the first century of the common era, Jews landed on the Malabar Coast of Kerala and settled near the port of Kodungallur. They became the Malabari Jews, and after a flood ruined the port in the 1300s, they moved to Kochi.

Kochi, red, is located in southwestern India. Map courtesy of Google Maps

Historians believe that the Malabari Jews were well received due to India’s pluralistic religious culture. So, when Spain and Portugal expelled Jews in the 15th century, some settled in Kochi because they knew they would be welcome.

The two communities practiced their religion differently. So despite the two Malabari synagogues in Mattancherry, and another five in surrounding Kerala, the newcomers wanted their own. By the mid-1600s, they had built the Paradesi Synagogue and did not allow the Malabari to participate in services.

Today, the Paradesi Synagogue theoretically serves both communities — the three remaining Paradesi Jews, and the 21 Malabari. The only synagogue in the city with a rabbi struggles to assemble a minyan, or the minimum of 10 men needed for a complete Sabbath service. So the synagogue relies on Jewish tourists from around the world for its weekly worship.

- A curtain covers the entrance to a former synagogue in Kochi, India. The sign above the doorway is from Tehillim, Psalms, Chapter 118, verse 20: “This is the Lord’s gate; the righteous will enter therein.” Photo by Aaron Schrank

- Sarah Cohen, seen here in the early 1960s, has sewn and embroidered kippahs, challah covers and table linens since her youth. Courtesy photo

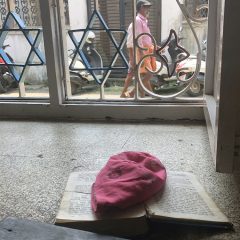

- Sarah Cohen’s Torah sits in her window in Kochi, India, which is now home to only 24 local Jews. Photo courtesy of Aaron Schrank

At one service, an Israeli family of eight walked in, leaving their shoes at the door, per Indian custom. The women settled in at the back of the synagogue — in keeping with Orthodox Jewish tradition, in which men and women sit in separate quarters divided by a screen. (Years ago, the women sat in the balcony, but these days the elderly Jews can no longer make it up the stairs.) A few more tourists trickled in, but still, not enough for a service. The rabbi explained the situation to the congregants, led an altered prayer service and invited everyone for lunch.

Outside, Talia Cohen smiled.

“It’s funny because the rabbi said it’s sad that the synagogue is empty. But for us we’re happy, because it means the Jews are home. It’s Shabbat, and they’re in Israel,” she said, referring to the Indian Jews who have made aliyah, or immigration to Israel.

Sarah Cohen, 96, watches a tourist group outside her window. Photo courtesy of Aaron Schrank

The last Paradesi Jew of childbearing age left with her mother in recent months.

Sarah Cohen is staying put. India has always been her home, and Ibrahim said the elderly woman does not want to leave the place where her husband and brother are buried and where her home is only a few yards from the synagogue.

Some residents hope tourism will provide an incentive to preserve the landmarks of Kochi’s Jewish community, like the Paradesi Synagogue and the Kadavumbagam Synagogue in the aquarium store — even if some Jews can’t make it to the synagogue.