(RNS) — In the early 2000s, Jeff Sharlet was invited to live at Ivanwald, an Arlington, Va., house run by the Fellowship Foundation, the nonprofit group behind the National Prayer Breakfast.

He thought the experience would fit in a book he was writing about religion in America. Instead, he stumbled into the story of a lifetime, about a secretive Christian group whose membership, largely elected officials and wealthy businessmen, has helped shaped our politics for more than 50 years.

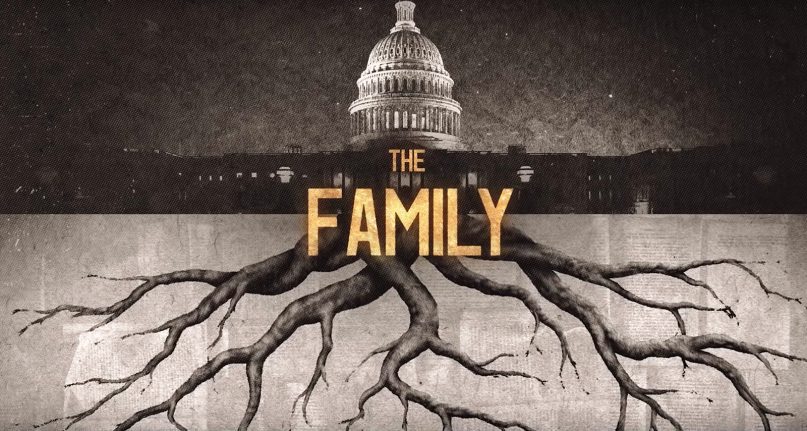

They call themselves the Family. They work behind the scenes through relationships forged at Bible studies, prayer breakfasts and private meetings with leaders from around the globe.

Family members have befriended dictators such as Ferdinand Marcos, Moammar Gadhafi, Suharto – offering friendship in the name of Jesus to promote political ends. Members often did so in secret at the behest of their longtime leader, the late Doug Coe, who often told his followers, according to Sharlet, that Jesus did not come to reach the poor or the outcast, but to help the powerful.

Sharlet’s books on the Fellowship, “The Family” and “C Street,” are the basis for a new five-part Netflix documentary series that traces the Fellowship’s history from its founding in 1935 by Abraham Vereide, a Methodist minister, to the 2018 National Prayer Breakfast.

Religion News Service Editor-in-Chief Bob Smietana spoke by telephone recently with Sharlet and with Jesse Moss, the series’ director. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Director Jesse Moss, left, and Jeff Sharlet chat during a production break. Courtesy photo

What’s been the response to the series on Netflix?

Sharlet: It’s been pretty tremendous. The two things I was afraid of were, one, right-wing anger. But even conservatives are saying, “Oh, this is a problem.”

The other thing I was afraid of is that people would not get it. When someone like a Jerry Falwell pounds the pulpit and starts talking about “the gays” and all this kind of thing, that’s easy to understand. The Family is much smoother.

So that is the good news. The bad news is that so many people are saying, ‘I didn’t realize this.’ We all need to be a little bit more literate if we’re going to hold on to this democracy.

The members of the Family who appear in the series are very earnest about what they are doing. You’re not simply saying, “Look at how bad these people are.” They have a chance to explain what they are doing and why they do it.

Moss: They have a point of view, and it was important to represent that point of view. Getting their cooperation was time-consuming. We only ended up with Zach Wamp and Larry Ross at the end of a long dialogue. But finding people who were still willing to talk to us and who were deeply inspired by Doug Coe and in some way, this movement — those were essential conversations for me.

Doug Coe, left, meets with the Reagans in the Netflix series “The Family.” Photo courtesy of Netflix

Sharlet: I just had an exchange this afternoon that I thought was revealing. A member of the Family had been writing to me, very upset. She was very close to Doug Coe and she loves him and says, “How can you say these things about him.” My response is we don’t actually say too much about him. We’ll let him do the talking and we let the record of his actions speak for themselves.

And I said, look, you know, this is not an anti-Christian message. I’m not a Christian, but I’m incredibly compelled by the Christ who cares for the least of these.

Her response — and this is coming from a place of deep earnestness and even hurt on her part — was that Doug served, you know, a Christ who cared for the powerful. She said that “it seems like you have some sort of problem with people in power.”

Yes, I do, as a journalist whose job is to speak truth to power, as a citizen of a democracy whose job is to question power. And as someone who has been very interested in faith for a long time and been compelled by the whole history of Christian witness. Christian witness is not about cozying up to power.

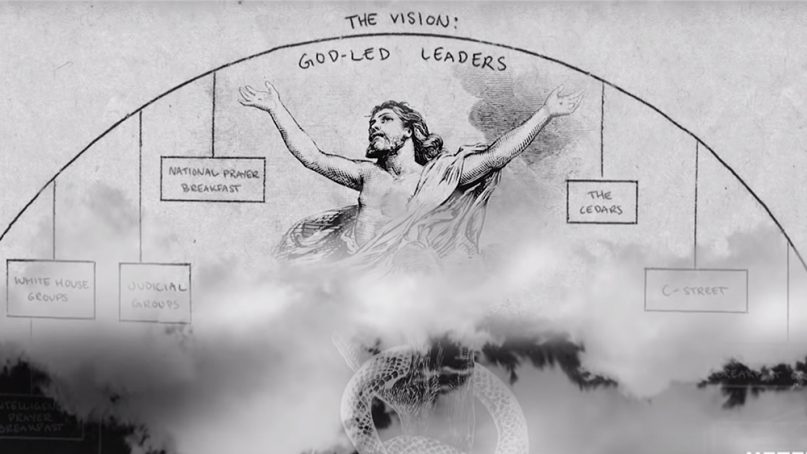

Do you think members of the Fellowship are after power for power’s sake? They seem to have a post-millennial motivation — we’re going to make God’s kingdom. And the way we are going to build it isn’t by democracy.

Sharlet: I think you’re right about post-millennialism and that is something I have argued for a long time. That’s part of what historically has made it difficult for the press to understand their work. Secular folks, when they think of politicized Christianity, they think about rapture theology. And even now people say, those guys can’t wait till the end of the world.

Russians Mariia Butina and Alexander Torshin at the 2017 National Prayer Breakfast. President Trump later spoke from the podium in the background. Photo via Facebook

That’s not these guys, that’s not the project. They’re in it for the long game.

I think we have to decide if that is right. Do you think preaching a gospel of American power, and anti-LGBTQ values in Romania and putting American power behind that is the right side? Do you think covering up the affairs of the powerful so that they can stay powerful is being on the right side?

Moss: This tension is clearly embodied in the third episode, about the National Prayer Breakfast and in the story of Mariia Butina. Was she pure of heart and spirit when she came to the prayer breakfast? Or was she exploiting this transactional event with a network of powerful people?

Is this naiveté or cynicism? The answer is the Fellowship manages to be both.

Let’s talk about naiveté. Some of these politicians have to know that when they show up at a foreign leader’s office, they are not just a brother in Christ. They are representatives of the U.S. government. But they seem to want to set that aside and say, I just love you in the name of Jesus.

Moss: That contradiction is embodied in Mark Siljander, who tells his own story about trying to pray with Gadhafi. What could be wrong with that? You know, just a prayer for peace. On the other hand, Siljander was using the Fellowship to launder money and went to prison for it.

Sharlet: In their own documents, Coe, and certainly many of the political leaders, were fully aware that they were using American power to pry doors open on behalf of this particular religious project. They would be explicit about this in their correspondence. And that to me is a deeply cynical exercise.

When Coe says from now on, we’re going to submerge the institution. We’re not going to use our own letterhead (to invite people to the prayer breakfast.) Use congressional letterhead so it looks like it’s coming from Congress. That’s deception. That’s just deception.

“The Family” premiered recently on Netflix. Photo courtesy of Netflix

I wonder if you could talk about Doug Coe’s parable of the wolf king.

Sharlet: Going back way back to my days at Ivanwald, they were always sort of talking about the sheep and wolves. I remember hearing them asking, what if Christ came not for the sheep but for the wolves? This becomes more articulated in this parable of the wolf king. The idea is that the leader of the pack is the most powerful figure. And you can go to the most powerful figure and you can pry open that door and say, let’s come alongside you.

The movement sought out wolf kings around the world — in Indonesia and Somalia, Guatemala and El Salvador — and lent American support to those regimes.

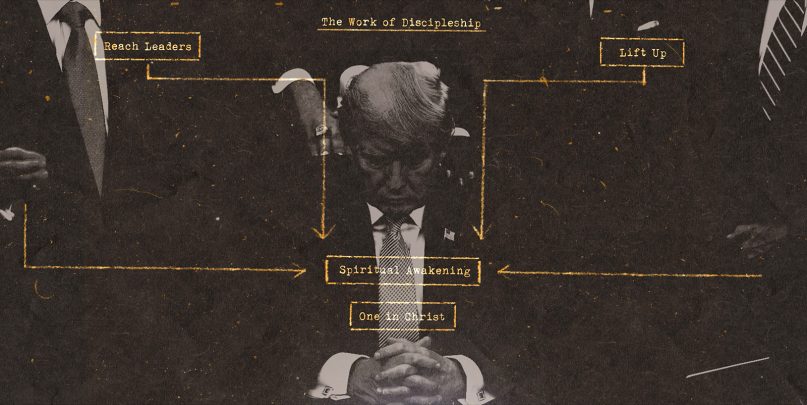

But within the United States, they still had to work within this shape of democracy. Now at last Trump, the wolf king, has arrived at home. And it doesn’t matter that he’s a believer. The wolf king likes strength and you’re going to put your strength alongside his. That’s the transitional moment we see in the film that we’re in. The Family’s practices that were once mainly just overseas are now coming home.

President Trump speaks during the National Prayer Breakfast on Feb. 2, 2017, in Washington. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

For those of us who report on religion in America, it’s no secret that there have been elite religious leaders for a long time who were willing to make deals with leaders they knew to be “imperfect vessels,” as the Fellowship calls them.

And yet public religion always depended on, at the very least, the veneer of piety. Liberals tended to see that as hypocritical, but I think they missed that it functioned as a form of accountability. Even if they adhered to values that secular folks would find offensive or hateful, there’s still a form of accountability.

Now we see white conservative evangelicalism engaging in this transactional religion with the politics of Trump in which accountability doesn’t matter. In which the ends do justify any means.

I think that’s an evolution.

A still featuring President Trump from the Netflix docuseries “The Family.” Image courtesy of Netflix

The Family seems to reflect the influence that business leaders have in evangelical religion. Most of the leaders are Christian businessmen or politicians, rather than clergy. And they seem to have a disdain for religion.

Sharlet: That’s the ethos of “Jesus plus nothing.” And the appeal. “Oh, you haven’t read the Bible, that’s fine. Religion is too complicated.” Christ without Christianity absolves you of any responsibility for misinterpretation and allows you to do whatever you want and say it’s in Jesus’ name.

It shows the way good intentions can go disastrously awry.

Moss: Good people make catastrophic and terrible decisions. And bad people may even have some goodness in their hearts somewhere.

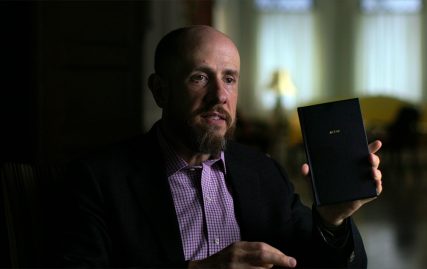

Can you talk more about the Fellowship’s idea that some people are chosen by God as leaders?

Author Jeff Sharlet in “The Family” on Netflix. Photo courtesy of Netflix

Sharlet: I mean, wouldn’t that be amazing if you got a message from God that you are chosen? Not the person next to you. You are special. You are on a special mission. And as evidence of this, you’re on a private jet and you’re meeting with a president of a foreign country and there are powerful people all around you.

Everybody is crying and everybody is gentle and you say, you know what? We’re going to cut through all the crap and finally do good. Who could say no to that? Not many.

Moss: When I read Jeff’s book, I love how he encountered this group kind of innocently, then his perspective shifted. I thought, how can we give the audience that experience, to see the attraction that comes from being in the small and intensely devoted group of people? It’s not hard for me to see the appeal of being in a brotherhood.

For me personally, it was not till I went to visit a group in Oregon and sat with those men and they said, well, you have to be in this group if you are filming it. I’ve never participated in any kind of small group therapeutic conversation and I loved how they challenged me.

They said, look at your crew. It’s all white. What’s wrong with you? And I, you know, fumbled for a response. It’s so unusual to encounter a space where people are talking honestly, in this case about race. There’s something, something here that I can relate to and I wanted to show that to the audience.

Doug Coe in 2016. Coe died on Feb. 21, 2017. Photo courtesy of A. Larry Ross

You show Doug Coe talking about the need for secrecy and about Nazis and you think, who is this guy? Then you see him talking one-on-one with people and he’s so gentle. How can we reconcile these two sides?

Sharlet: To me, that’s not a contradiction at all. This is the naiveté of American political life. We see a man who is kind and we are willing to look away from a well-documented record of a person who, given the choice between power and a witness to the faith, chose power every single time.

(Editor’s note: RNS reporter Jack Jenkins appears in the Netflix series.)