(RNS) — American scholars who study faith are grieving the passing of Wade Clark Roof, 80, a sociologist of religion who leaves a towering legacy as an academic, helping Americans grasp the spiritual lives of the Baby Boomer generation. He is also known for investing in the careers of those he mentored.

“Nobody’s perfect, but boy, he was remarkable,” said Diana Butler Bass, a historian of religion who knew Roof.

News of his death over the weekend sparked an outpouring of warm remembrances among a small social media community of religious scholars on Twitter, using the hashtag #WadeClarkRoof to recall Roof’s influence.

“Mourning the passing of my mentor, dissertation chair, and friend, sociologist Wade Clark Roof,” wrote sociologist, professor, and author Tricia Bruce. “Celebrating a life well-lived.”

Roof’s friends recounted the life of a man who grew up in the Sandhills region of South Carolina, the same state where he attended Wofford College for his undergraduate studies. Roof eventually enrolled at Yale Divinity School to earn his master’s degree, which he later described as an experience that exposed him to “liberal influence.”

That influence did not sit well with everyone back home. Roof told The New York Times in 1993 that when he returned to his home state after divinity school to become a Methodist minister in Spartanburg, South Carolina, he was “stigmatized” as being “more liberal than I was.”

Wade Clark Roof. Photo by Tony Mastres/UCSB

But in practice, Roof still leaned left compared to his congregants, according to Julie Ingersoll, another renowned scholar of religion who describes Roof as a friend. “He wanted to integrate the church, and the elders just wouldn’t have it,” Ingersoll recalled Roof explaining. “He was invited to leave, so he decided to go to grad school,” after only two years in ministry.

He went on to attend the University of North Carolina from 1966 to 1970, studying religion and race relations before ultimately receiving his Ph.D. from the school in 1971. By then Roof had already taken a job as an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, where he would remain for 19 years, teaching sociology courses on religion, race and American society.

In 1989, he moved with his wife Terry to California, after being appointed to the religious studies faculty at the University of California Santa Barbara, where Roof created the Walter H. Capps Center for the Study of Ethics, Religion and Public Life.

“That was an extraordinary labor on his part,” recalled Shawn Landres, a former student of Roof’s who went on to cofound the nonprofit Jumpstart Labs and serve as a municipal commissioner in Santa Monica. “Public understanding of religion was a relatively new idea.”

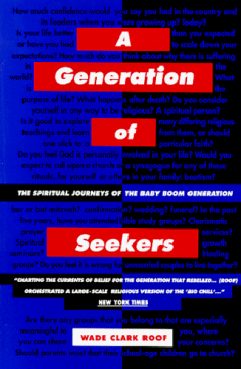

But Roof is perhaps best known for what he created when he got there: his 1993 book “A Generation of Seekers: The Spiritual Journeys of the Baby Boom Generation.”

“Religion in the United States is like a brilliantly colored kaleidoscope ever taking on new configurations of blended hues,” Roof would later write in an updated version of the book.

According to Bass, the book, which drilled-down on the religious lives of the Baby Boomer generation, was pioneering for its unapologetic inclusion of ethnographic work alongside more traditional, data-focused sociological study.

“He was part of an argument to move away from seeing sociology of religion as purely about numbers, and instead understand (it) as the lived experience of people in community,” Bass said. “While (his book) was very important in terms of quantitative sociology, it was also a lively example of a new ethnographic turn in the sociology of religion.”

A Generation of Seekers: The Spiritual Journeys of the Baby Boom Generation” by Wade Clark Roof. Image courtesy of Harper San Francisco

The book is widely understood to have made a mark not just on academia but also on religious communities themselves. Bass said it became popular in seminaries and other faith communities, with religious leaders poring over Roof’s thoughts in order to better understand a generation that was returning to church as it grew older.

“It was an incredibly significant work,” Bass explained. “It made an impact on both the church and the larger academy. It was also picked up by Baby Boomers themselves, who said, ‘Oh my gosh, this is my experience!’”

Both Ingersoll and Bass remember Roof as a warm mentor figure who regularly welcomed students and friends into his home for conversation with him and his wife. His collegiality, they said, was an important part of his impact on his field.

“Because he had that ability to really connect with people one on one, he had deep influence in all kinds of different venues,” said Ingersoll.

Landres agreed.

“I think I learned more from him outside the classroom than inside,” said Landres, who noted that Roof once wrote an article about religion and barbecue. “For him, part of being in the academy was to have a complete, human relationship with your students.”

Bass noted that Roof regularly attended Trinity Episcopal Church, a struggling congregation that grew from less than 100 attendees to more than 400 — in part, she said, because the church’s leaders incorporated lessons from Roof’s research on spirituality into their work.

Ingersoll, who lived in a cottage in Roof’s back yard while studying in California, recalled her professor’s meticulously cultivated garden, the pruning of which he referred to as his “therapy.” He was also an avid dog lover and learned to fly fish.

To be sure, Roof went on to publish a number of books and remained a giant in the field of sociology of religion up until his death. He was slated to receive the Martin E. Marty Award for the Public Understanding of Religion from this year’s American Academy of Religion conference.

But if you ask his former students and acquaintances, Roof’s most lasting presence will likely be felt not in libraries but in those he mentored. For them, one of his most powerful contributions was his ability to look beyond the numbers he so often parsed to see the humans they represent.

“I think that his biggest continuing impact is going to be through the lives of the students that he trained, dozens and dozens of them now are professors themselves at universities across the United States and even a few across the globe,” Bass said.

Roof, whose wife passed away in 2018 after a lengthy battle with breast cancer, was the father to two daughters and six grandchildren.