ELKINS PARK, Pa. (RNS) — Sixty years ago this week, just before the Jewish High Holy Days, members of a Conservative synagogue processed into their new sanctuary, marking a new era in their congregational life and in modern religious architecture.

The only synagogue designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, Beth Sholom Synagogue still stands six decades later in this suburb north of Philadelphia as both a house of prayer and an unusual, functioning piece of art.

Recalling in its design the place where Scriptures say the Ten Commandments were given to Moses, Beth Sholom is lesser known than the Guggenheim Museum in New York, Fallingwater or his other landmark creations. It nevertheless attracts those who are aware of its connections to the famous architect, and Wright himself saw it in cosmic terms.

“The design for Beth Sholom has taken the supreme moment of Jewish history and experience,” said Wright at the time, “the revelation of God to Israel through Moses on Mount Sinai, and translated that moment with all its significance into a design of beauty and reverence.

“In a word, the building is Mount Sinai, where Israel first encountered God.”

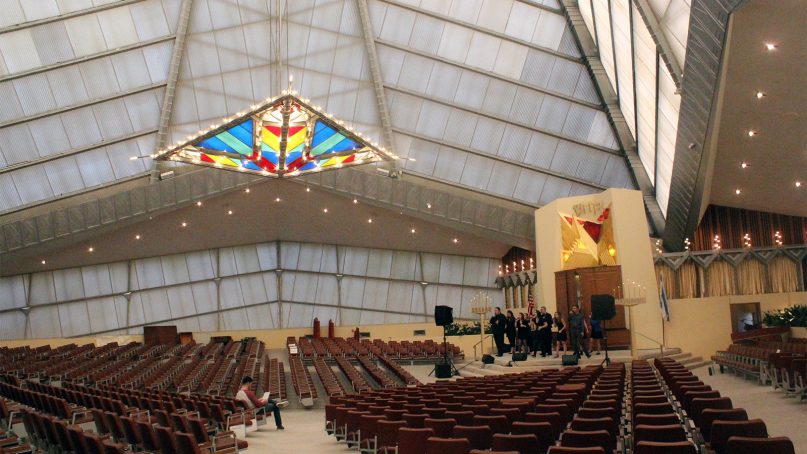

A choir rehearses at Beth Sholom Synagogue in November 2018. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

The synagogue’s exotic geometric shape, which appears atop a rise and around a bend as drivers approach it along Old York Road, was suggested by Beth Shalom’s then-Rabbi Mortimer J. Cohen as “a dream and hope in my heart” to Wright in a 1953 letter. Wright responded to Cohen, whose letter included a rough sketch of his idea, beginning a close bond the two men developed mostly through correspondence.

“They had a very long, sustained dialogue about this building over a six-year period,” said Joseph M. Siry, author of the 2011 book “Beth Sholom Synagogue: Frank Lloyd Wright and Modern Religious Architecture.”

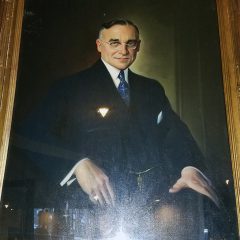

- A portrait of Rabbi Mortimer J. Cohen at Beth Sholom Synagogue. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

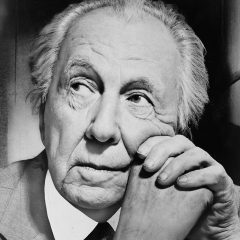

- Architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1954. Photo by Al Ravenna/LOC/Creative Commons

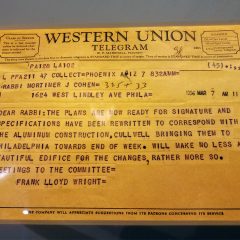

- A 1956 telegram from Frank Lloyd Wright to Rabbi Mortimer Cohen on display at Beth Sholom Synagogue. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

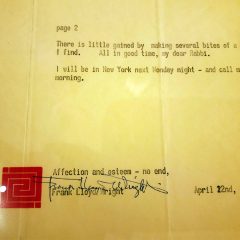

- A 1958 correspondence from Frank Lloyd Wright to Rabbi Mortimer Cohen on display at Beth Sholom Synagogue. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

Wright would eventually grant Cohen the title of co-designer. The architect, a Unitarian whose uncle was an organizer of the 1893 Parliament of the World’s Religions, also referred to the rabbi and himself as “congenial workers in the vineyard of the Lord.”

Siry said Cohen, in turn, said: “I found in Mr. Wright a genuinely spiritual person who responded in his unique way to the great teachings of my religion.”

The building was dedicated, and the rabbi’s dreams were realized, just months after Wright’s death, on Sept. 20, 1959.

Cohen showed in his original sketch that he did not want a traditional longitudinal design. Rather, he desired a space, Siry said, with “a much more collective, in-the-round feeling.”

The interior of Beth Sholom Synagogue, featuring an installation exhibit by artist David Hart titled “The Histories (Le Mancenillier)”. Photo by Michael Vahrenwald

That idea continued in the slant of the floor.

“It slopes down toward the front but it also slopes in toward the center,” said Siry, an art history professor at Wesleyan University in Connecticut.

For his part, “Wright wanted to create the ‘kind of building in which people, on entering it, will feel as if they were resting in the hands of God,” the American Institute of Architects notes in its online description.

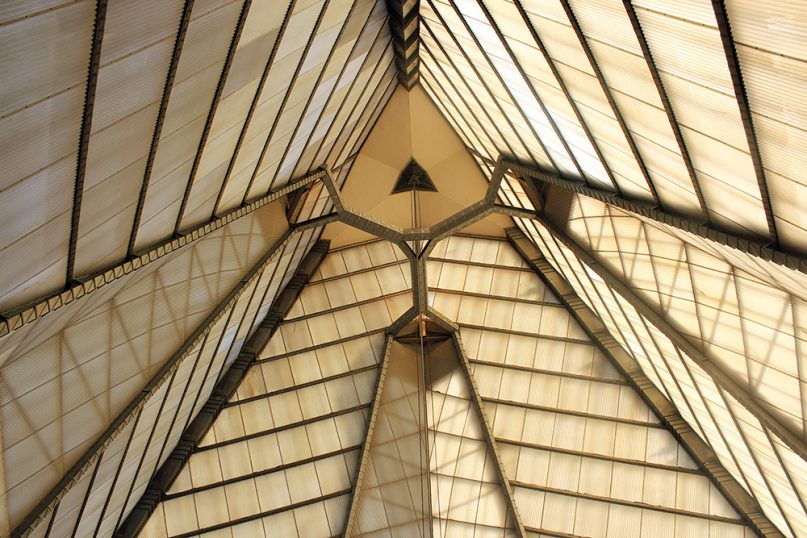

Siry said the building, with its 108-foot-tall sanctuary, achieves the “mountain of light” Wright was hoping for with the synagogue’s tetrahedron design.

The exterior of Beth Sholom Synagogue at night. Photo by Laszlo Regos

“It has this translucence, which is very special both from the inside during the day and from the outside at night when it’s lit from the inside,” said Siry of the two-layered wall of glass and plastic that makes up the surface of the tent-like structure. “It’s very striking and pronounced at night when the synagogue is lit from within.”

Just before night falls, said Helene Mansheim, director of the synagogue’s visitor center, the light from the sunset can turn the sanctuary a golden color.

The interior vaulted ceilings of Beth Sholom Synagogue. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

Designated a National Historic Landmark in 2007, the synagogue is listed by the AIA as one of 17 buildings designed by Wright that are examples of “his architectural contribution to American culture.”

Recently, new sights and sounds have been added to the synagogue, whose name means “House of Peace.”

In part to mark the building’s 60th anniversary, Beth Sholom’s preservation foundation has commissioned a multimedia installation by Philadelphia artist David Hartt that evokes the Jewish and African American diasporas.

Installation exhibit by artist David Hartt titled “The Histories (Le Mancenillier)” at Beth Sholom Synagogue in Elkins Park, Pa. Photo by Michael Vahrenwald

The exhibition, titled “The Histories (Le Mancenillier),” features orchids and other tropical plants, along with tapestries, videos and the music of composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk. The composer, who was born to a Jewish father and Creole mother, wrote a piece called “Le Mancenillier,” the French word for a manchineel, a sweet, poisonous tropical plant.

Cole Akers, curator of the exhibition, said the installation reflects how Beth Sholom’s congregation, a century old this year, has related to urban development. The congregation began in north Philadelphia in a building that has become the location of Beloved St. John Evangelistic Church in a community that is now predominantly African American.

“The relationship between these two congregations led Hartt to consider the constant movement of Black and Jewish communities as a result of political, economic, and social currents,” Akers said in an email message.

Installation exhibit by artist David Hartt titled “The Histories (Le Mancenillier)” at Beth Sholom Synagogue in Elkins Park, Pa. Photo by Michael Vahrenwald

Herb Sachs, president of the Beth Sholom Preservation Foundation, said Hartt’s exhibition also reflects the practical realities of the building.

“Most Frank Lloyd Wright buildings leak and ours is no exception,” he said. “He maps where the rainwater tended to be collected and he’s placed orchids in each of those locations.”

The recorded music playing throughout the show was arranged by Ethiopian pianist Girma Yifrashewa, who created it using nine microphones inside and outside of the instrument, which makes for an ethereal sound.

“When one is sitting in the sanctuary you feel as though you’re sitting in the middle of a piano,” Sachs said. “And then observing these orchids and tropical flowers, it’s a very peaceful feeling and I think visitors are enjoying it.”

The exhibition, which opened last week (Sept. 11), will close Sept. 26-Oct. 10 around the time of the High Holy Days and reopen through Dec. 19.

Mansheim, director of the visitor center, said the installation is a fitting addition to the nontraditional house of worship.

“The building is a work of art,” she said. “So, here’s a chance to show another work of art.”

Frank Lloyd Wright’s signature red tile on the Beth Sholom Synagogue. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks