We are fast approaching the tricentennial of anti-vaccination agitation in America. Given where we are today, it’s worth recalling the cautionary tale of Episode One.

In 1721, Cotton Mather, Boston’s foremost cleric, sought to stem a smallpox epidemic by persuading a local doctor to try inoculating people against the disease. The procedure, which Mather had learned about from his enslaved West African servant Onesimus, was risky, since it involved infecting people with a bit of the live smallpox virus.

Public resistance ensued that found its way into the local press, then barely two decades old. One newspaper, the New-England Courant, embraced opposition to inoculation as its virtual raison d’être. The paper would, it declared, “pray hard against Sickness, yet preach up the POX!”

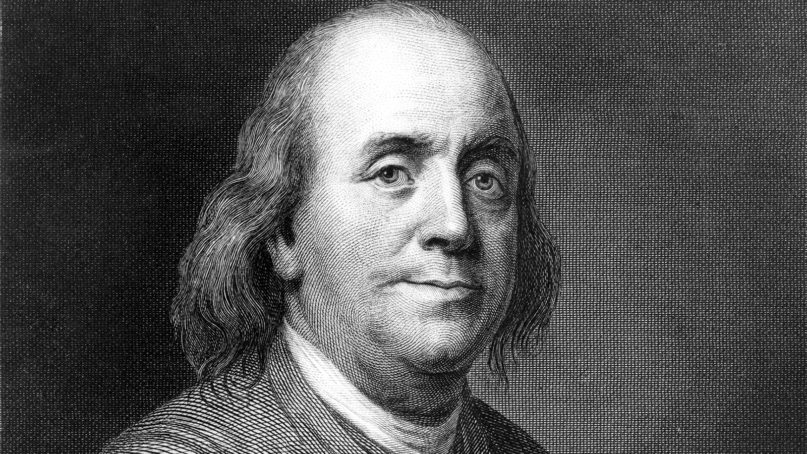

The publisher was James Franklin, who had been set up in the business by local Anglicans precisely in order to undermine the authority of Mather and the rest of the Commonwealth’s Puritan establishment. Franklin’s 16-year-old brother Benjamin joined in the campaign, accusing the pro-inoculation clergy of hypocrisy in one of his pseudonymous “Silence Dogood” letters. “I affirm it unlawful,” the imaginary lady wrote, “for a Person in health upon any Account to receive a less Infection to avoid a greater, because Our blessed Saviour, the Great, the Skillful Physician says, He that is whole needs not a Physician, but he that is Sick.”

In the face of the Courant’s assaults, Mather’s aged father, Increase, was moved to write to the establishment Boston Gazette declaring himself “extreamly offended” at the publisher “because in one of his Vile Courants he insinuates, that if the ministers of God approve of a thing, it is a Sign it is of the Devil; which is a horrid thing to be related!” The letter went on to recall a time when the government of Massachusetts would have suppressed “such a Cursed Libel” and in due course, the Courant was in fact investigated by a committee of the Massachusetts Legislature, which concluded that the paper had both mocked religion and affronted the government.

It was no coincidence that Benjamin Franklin took off for Philadelphia shortly thereafter, where his evidently sincere opposition to inoculation had tragic consequences. As the leading American scientist of his era wrote in his autobiography:

In 1736 I lost one of my sons, a fine boy of four years old, by the smallpox taken in the common way. I long regretted bitterly and still regret that I had not given it to him by inoculation. This I mention for the sake of the parents who omit that operation, on the supposition that they should never forgive themselves if a child died under it; my example showing that the regret may be the same either way, and that, therefore, the safer should be chosen.

Altogether, the similarities to the contemporary anti-vaccination war are uncanny. There’s the anti-establishment impulse, the media role, the ambient religious distress, and the eventual government involvement. These days, the last of these has, like so much else in American life, acquired a partisan dimension.

A few weeks ago, the powers that be in Connecticut state government got on the same page when Democratic Gov. Ned Lamont and his health commissioner joined the Democratic leadership in the General Assembly in supporting repeal of the state’s religious exemption for vaccines. The move was opposed by the dozen Republican members of the legislature’s Conservative Caucus, on the grounds that the state constitution’s guarantee of free public education to all children guarantees unvaccinated children the right to go to school.

In California, not a single Republican voted for legislation that passed early in September giving the state more oversight over doctors who help parents skirt mandatory school vaccinations. In New York, just one state Republican senator and three Republican members of the Assembly voted for the bill that became law in June requiring children in public school to be vaccinated. In Oregon, which has the lowest rate of measles vaccination in the country, the same partisan divide led the Democratic governor to cut a political deal that killed a vaccine bill that had passed the state House of Representatives in May.

Although anti-vaxxers can be found in many corners of American life, the Republican Party is where anti-establishment populism and religious exemptions from government mandates have found their political home. Benjamin Franklin lived to regret his opposition to inoculation. The time for the GOP to do the same appears far off.