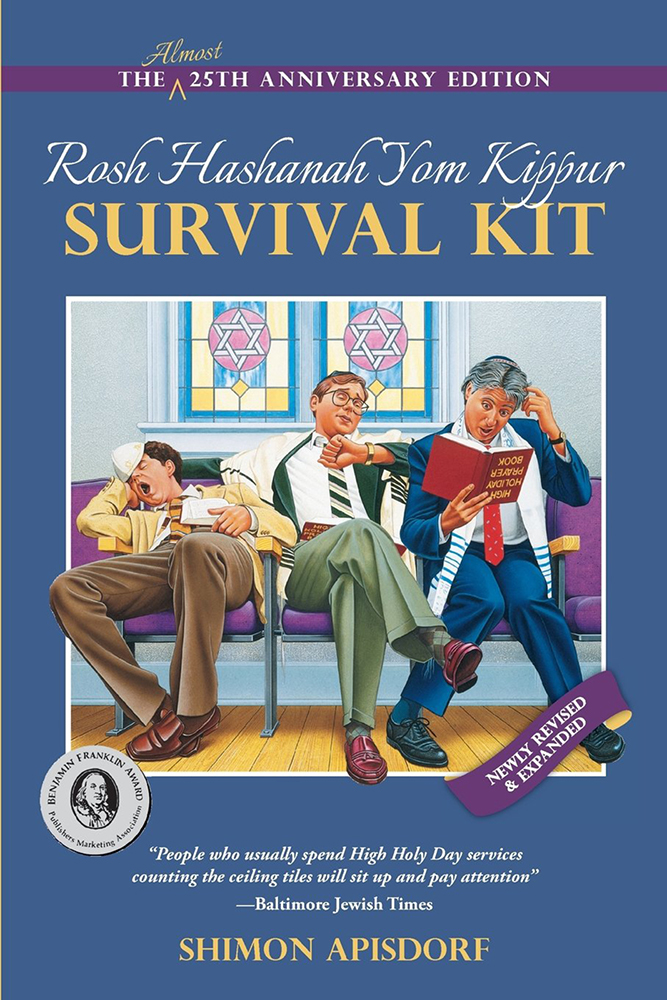

“Rosh Hashanah Yom Kippur Survival Kit” by Rabbi Shimon Apisdorf. Image courtesy of Leviathan Press

(RNS) — Rabbi Shimon Apisdorf’s more than 25-year-old book, “Rosh Hashanah Yom Kippur Survival Kit,” has a cover to which many Jewish High Holiday worshippers can relate. Dressed in their synagogue best, three men sit before stained-glass windows adorned with Stars of David. One holds his prayer book upside down, looking baffled, while his neighbor checks his watch. The third has fallen asleep with his yarmulke nearly covering his eyes.

The High Holidays, which began this year on the evening of Sept. 29, culminate in what many believe to be the judgment of who will live and who will die the following year. As dramatic as that might seem, spending nearly the entire day in synagogue on Yom Kippur, and the better part of the day doing so on Rosh Hashana, can be less than exciting. Apisdorf’s book and its cover strive to help readers get beyond the inevitable yawns, boredom and leg cramps.

Some 115 years prior, Jewish Galician painter Maurycy Gottlieb (1856-79) captured the sometimes-tedium of being in synagogue on the High Holidays in a very different manner. Gottlieb’s 1878 painting “Jews Praying in the Synagogue on Yom Kippur,” which is in the collection of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, shows the synagogue’s men’s section in the foreground, where a seated rabbi holds a Torah scroll, and the women’s balcony in the rear. As in Edward Hopper’s paintings, few of the figures appear to acknowledge one another.

The work, which Gottlieb painted the year before he died, is an intensely personal one. In the painting, Gottlieb thrice depicted himself: as a child in the bottom left corner; as a slightly older boy on the extreme right; and in the center of the composition, clad in what some scholars have referred to as Joseph’s technicolor dreamcoat, with his head resting in his hand.

“Jews Praying in the Synagogue on Yom Kippur,” by Maurycy Gottlieb, from 1878. Photo by Avraham Hai, courtesy of Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Gift of Sidney Lamon, New York, 1955

In the women’s balcony, Gottlieb twice featured his fiancée, Laura, who had already broken off their engagement and who would marry another. Laura holds her prayer book standing on the left, and then whispers in or near her mother’s ear on the right.

Scholars have praised this painting thoroughly. It was “the first modern masterpiece on a Jewish theme by a Jewish artist in Poland,” wrote Gilya Schmidt, professor and director emerita of University of Tennessee, Knoxville’s Judaic studies program, in the book “The Art and Artists of the Fifth Zionist Congress, 1901.”

The work, Schmidt added, expresses the artist’s personal suffering, “lifting him out of the mass melancholy that pervaded diaspora life, though enveloping him in Jewish tradition, family, and friends.” Schmidt noted that all the other figures in the work are members of Gottlieb’s family.

In the essay “Jewish Identity in Art and History: Maurycy Gottlieb as Early Jewish Artist,” Larry Silver, art history professor emeritus at University of Pennsylvania, described the painting’s contradictions. “This work is Gottlieb’s fullest affirmation of his Judaism as well as his most careful observation of the customs, costumes, and settings of Jewish religious life in the sanctuary,” he wrote. “However, the scene also portrays Gottlieb himself as a pensive outsider … dreamily turning his attention away from the prayer that absorbs the rest of the congregation.”

The solemnity of the day is amplified by the Hebrew inscription Gottlieb painted on the Torah scroll mantle — then removed when his father objected but subsequently re-added — which notes the scroll has been donated in memory of the late and righteous Rabbi Moshe Gottlieb, invoking the artist’s Hebrew name.

Gottlieb would have almost certainly known of the Jewish anxiety around inviting the “evil eye” by suggesting he would die soon, but the painter nonetheless saw this painting as memorializing himself. He did, in fact, die not long after either from health complications, or as the Tel Aviv Museum of Art noted, “He apparently died in broken-hearted anguish, either of natural causes, or — as some believed — by committing suicide.”

Asked what viewers today can take away from the painting and its commentary on what it feels like to attend Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur services, a Tel Aviv Museum of Art curator said the painting relates to the artist’s “very personal situation” and that Gottlieb chose to depict his own Yom Kippur experience “as part of an emotional conflict that he was (in) at the time it was painted.” The curator declined to comment on how viewers should feel while looking at the work.

But standing in front of it, or to a lesser extent considering it online, it’s hard not to feel that this picture may well have judged and sealed Gottlieb’s fate in life-imitates-art fashion for the coming year. It’s certainly food for thought (if that’s permitted on a fast day) for worshippers in synagogue or temple who ponder High Holiday references to who will live and who will die in the upcoming year, 5780.