NEW YORK (RNS) — Award-winning author Colum McCann’s anticipated new novel, “Apeirogon,” is based on the unlikely real-life friendship between two bereaved fathers born into opposite sides of an internecine conflict over land, religion, finite resources and competing narratives.

Rami Elhanan, 70, an Israeli Jew from the western tip of Jerusalem, served in a tank repair unit of the Israeli army during the Yom Kippur War. His father came to Jerusalem in 1946, shortly after surviving Auschwitz. Bassam Aramin, 52, a Palestinian Muslim from Hebron, in the West Bank, spent seven years of his youth in an Israeli prison for hurling a defunct hand grenade at an Israeli jeep.

Their paths crossed at a Combatants for Peace gathering, an Israeli-Palestinian movement of ex-fighters committed to nonviolence. Rami’s daughter, Smadar, had been killed in a suicide bombing attack in the late 1990s on Jerusalem’s Ben Yehuda Street. A decade later, Bassam faced the same devastation. In 2007, his ten-year-old daughter, Abir, was killed by an Israeli rubber bullet near her school.

Bassam and Rami, united in grief, have since traveled the world to spread their mission of dialogue over violence. Through Combatants for Peace and the Parents Circle Families Forum, made up of more than 600 bereaved Israeli and Palestinian families, the duo has spent decades preaching bridge-building over division.

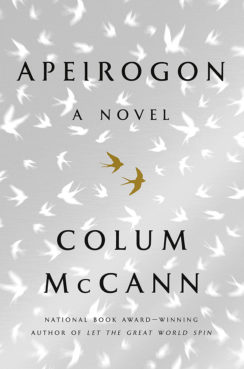

“Apeirogon: A Novel” by Colum McCann. Courtesy image

“Apeirogon” explores this surprising friendship and partnership in excruciating, kaleidoscopic detail. “I wanted to tell a story that anyone who knew nothing about the conflict could understand, but at the same time write it for people who absolutely understood the nuts and bolts,” the Irish-born McCann said in a recent interview. An apeirogon is defined in the novel as “a shape with a countably infinite number of sides,” an apt description of the innumerable complexities and perspectives that have defined this conflict and the many micro-narratives leading up to the senseless deaths of Smadar and Abir.

McCann, an international best-selling author whose 2009 novel “Let the Great World Spin” won the National Book Award, supports his apeirogon metaphor through the myriad, ostensibly tangential sub-narratives interspersed throughout the novel, which seem as random as the girls’ deaths. These include vignettes about bird migrations, Zyklon B, slingshots, Christ’s crucifixion and Philippe Petit’s high-wire walk over Jerusalem’s Arab and Jewish neighborhoods before releasing a white dove of peace in 1987.

While in New York on tour for the book, Aramin and Elhanan spoke to Religion News Service about “Apeirogon” and their unending fight for peace. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

What was your level of involvement in the making of “Apeirogon”?

Elhanan: Colum McCann was able to get under our skin and find unfelt ways to put together all the information he got from us in many, many interviews in New York, Jerusalem, Jericho and Beit Jala.

What has the reaction been like to the book?

Aramin: The reaction to the book in America has been amazing. We’ve been able to spread our important message of peace and humanity to a world of readers who, perhaps, might not have been familiar with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

What role has religion played in your lives?

Aramin: I’ve always been a religious person. It inspired my personality, my work, my activities, and I believe religion should be part of the solution and never part of the problem. As a believer, it’s my duty to act like a human being.

Elhanan: I’m not as religious as Bassam. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict today is not about religion, in my opinion. It’s about water, land, respect and human relationships. The moment it becomes a religious conflict, we’re doomed because you can’t compromise on religion. You can’t ask a Jewish person to keep only half of Shabbat and you can’t ask a Muslim to keep only half of Ramadan.

When you’re touring together, do people find it strange that the two of you are so close?

Aramin: Yes, and that is strange for us because I see this as normal behavior. There’s nothing more important for the two of us than our daughters. There’s nothing more painful for the two of us than losing our daughters. We’re now united to protect our other kids and raise them the right way. By appearing together, we’re sending a strong message of unity, not hate, to people across the world.

What makes you so optimistic about the future of Israel and Palestine?

Palestinian Bassam Aramin. Courtesy photo

Aramin: We’re optimistic about the future because of the past. We’re not going to continue killing each other forever. If you look back at history, the Israelis never killed six million Palestinians and the Palestinians never killed six million Israelis. Yet, today, we have a German ambassador in Tel Aviv and an Israeli ambassador in Berlin. We need brave leaders who are forward-looking and set aside the victimhood mentalities on both sides.

We’re two grieving peoples and we need someone to save us from this mentality, not feed us this fear. In Israel, I’m not concerned about whether the leader comes from the right or left — whether it’s Benny Gantz, Benjamin Netanyahu, Naftali Bennett or anyone else — if they truly want to end this conflict, they will be the right leader.

Elhanan: I’m not as optimistic. I don’t think any change is imminent, but the stars shine brightest in the darkest night. I have no doubt in my mind that one day we’ll have peace in our region, and this will happen the moment the price of not having peace will exceed the price of peace. Only then will both sides go back to the negotiating table and pick up where they left off 20 years ago.

What do you say to Israelis and Palestinians who have experienced pain and suffering and see violence as the only course of action?

Aramin: Instead of all of us enjoying Jerusalem’s holiness together, we kill each other for it. We either need to learn to survive together or we will share a land that will become two big graves because neither side is going to give up. We need to learn to exist together.

What role do the arts play in resolving this conflict?

Elhanan: The arts play a huge role. Look at the role a book like “Exodus” (by Leon Uris) had in the creation and justification of the State of Israel. Through music, media, arts, literature and painting, we’re hoping to change the narrative of two angry peoples who have hated each other. We can’t go on ignoring each other. Palestinians aren’t going to be able to throw Israelis into the sea and Israelis aren’t going to be able to throw Palestinians into the desert.

We’re doomed to live together, and it’s up to us to define how we’re going to live. It all comes down to respect. Everything else becomes a technicality the minute you are able to respect the other guy next to you exactly as you want to be respected. One state, two states, 10,000 states, confederations, federations — these are all technical solutions to a basic problem of respect.

Can you talk about your involvement in Combatants for Peace and Parents Circle?

Elhanan: I met Bassam in 2005 around the time Combatants for Peace was created. My eldest son, Elik, was one of the founders of the organization. Two years later, Bassam’s daughter was killed. He joined the organization the day after she died. Today, Bassam and I are co-directors of the organization.

Can the model of Combatants for Peace and the Parents Circle expand to other countries and other conflicts?

Aramin: Yes. At the Parents Circle, we’re the only organization on earth that does not actively seek new members. We don’t need to. When we meet families all over the world that are in pain, we instantly become friends and family. We understand each other and we don’t need to explain our pain. Our mission with Combatants for Peace is not only for Israelis and Palestinians — it’s universal.

Bassam Aramin’s daughter Abir, left, who was killed at the age of 10, and Rami Elhanan’s daughter, Smadar, who died at 14. Courtesy photos

Elhanan: This is the voice of humanity. This is the voice of sanity. These are the voices of people who have paid the highest price possible and understand that killing others won’t bring back our daughters. Inflicting pain on others will not ease our pain. This is not a group for psychological support. We believe we can bring about change by creating dialogue between Israelis and Palestinians and tearing down the wall of hatred, ignorance and fear that exists between the two groups.

What are the main misconceptions the two of you have encountered while you have been abroad touring for “Apeirogon”?

Elhanan: It took Bassam five years to get a visa to the United States. Last month, we arrived at LaGuardia Airport to get on a flight to Pittsburgh. We were stopped after Bassam presented his Palestinian passport. Bassam was humiliated. He was stripped of his clothes and searched three times. The border agents were completely ignorant of his background as a peace warrior. He was singled out by the system because he was a Palestinian Muslim.

I think this is the essence of the problem: Security has become a new religion. It has its own ceremonies and adherents, and it has nothing to do with security. It has everything to do with respect and human rights. The essence of the problem is ignorance and the inability to accept people who are a little different to us in the name of security. We see the same level of ignorance across Europe, too, where people have fortified their own identity and personality by being incapable of showing respect and mercy to people different to them.

When you meet people who say they want peace but have suffered and lost and don’t recognize Palestine for what it is or Israel for what it is, what do you say to them?

Elhanan: If you don’t recognize the legitimacy of the other, then you don’t want peace. We’re willing to talk and listen to anyone, but our starting point is the willingness to accept, understand and listen to the pain of the other. Only then can you expect the other to listen to your pain. If you’re not willing to listen or accept the pain of others, then you have to make peace with yourself first.

What message would you give someone who’s unfamiliar with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?

Elhanan: I’m the son of a Holocaust survivor. When the Nazis killed my grandparents, the free and civilized world didn’t lift one finger. And we see this today, which is horrible, because most of the casualties of this conflict are innocent people. Too many of them are children, and it’s a crime against humanity to let this conflict drag on. My other message is that I am a Jew with the utmost respect to my people, to my tradition and my history. But humiliating and occupying millions of people for so many years without any democratic rights is not Jewish to me. And being against this sort of behavior is not the equivalent to anti-Semitism, either.

Aramin: I live by two important quotes. One’s by Martin Luther King Jr., who said, “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.” The second is by the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, who once said, “I don’t have the time to hate those who hate me; I am too busy loving those who love me.”