(RNS) — For reasons I don’t need to explain, my family and I recently watched the 2011 movie “Contagion” together. In times like these we look for comparable situations. Everyone seems to be rediscovering the influenza pandemic that brought the world to its knees a century ago, shocked to find that every scourge like this shows a lot about our leaders and what they think will serve them best.

The first viral outbreak in U.S. history, however, comes much earlier, a few years after the Constitution was ratified, when Philadelphia faced an epidemic that killed 10% of the city. In those days, a small group of black Methodists displayed an unusual selflessness and dedication that revealed the heroism and frailties of a young nation.

The year was 1793. Philadelphia was a thriving, bustling city, filled with immigrants recently arrived from seemingly everywhere. Suddenly, all of Philadelphia was abuzz with word that yellow fever was spreading.

The city’s residents were accustomed to outbreaks of mumps, influenza and other diseases. Yellow fever was different. Caused by a virus carried by mosquitoes, it spread rapidly and with devastating effect.

RELATED: Click here for complete coverage of COVID-19 on RNS

The first response was the same as ours today: social distancing. The roads leaving town quickly overflowed with residents hoping to escape with their families and their lives. Those who remained faced a crisis that brought prejudices to the surface. By the time it was over, some 5,000 people were dead, and life in the city would never be the same.

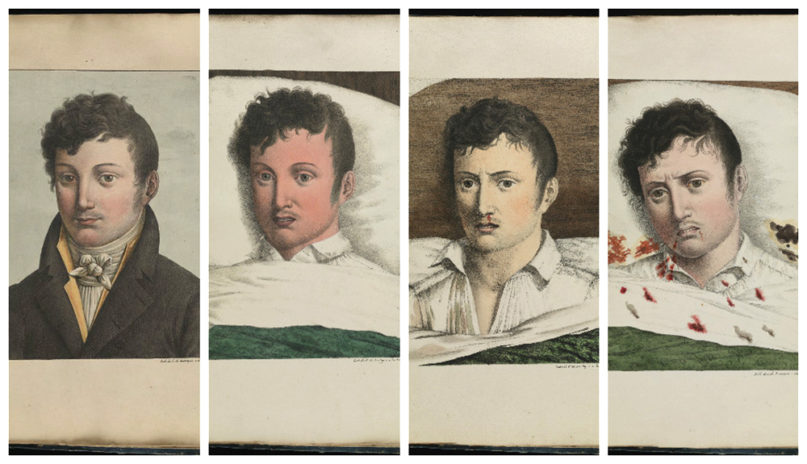

A series of 19th-century images depicting the development of yellow fever. Images courtesy of Wellcome Images/Creative Commons

To grasp the significance of those events, you need a bit of background about religion and race in the American experience.

In the 1790s, Methodism was a rapidly expanding religious movement along the Eastern Seaboard. In New York, Maryland and Virginia, Methodist preachers traveled on horseback from town to town. Originally dispatched by the Anglican John Wesley in England, these itinerant clergymen now served under the supervision of Francis Asbury.

Like Wesley, who shortly before his death in 1791 wrote that American slavery was “the vilest that ever saw the sun,” American Methodists were avowedly abolitionist. But local laws presented the traveling ministers with a difficult choice. They could avoid slaveholding regions altogether or try to gain access to slaves by working themselves into the good graces of plantation owners.

The latter approach occasionally proved successful. Sometimes a slaveholder might actually free their slaves. More importantly, the preachers often equipped the slaves with the knowledge that they, too, were bearers of the image of God, bolstering their dignity amid their dehumanizing circumstances.

Portait of Richard Allen by R. Davis on display at the World Methodist Museum in North Carolina. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

American Methodists would eventually divide over slavery when a bishop was discovered to have kept some inherited slaves; their official split in 1844 along geographical lines may be regarded as a harbinger of the coming Civil War. But in the 1790s, their emphasis on free grace meant the fledgling denomination grew rapidly among both blacks and whites. A black Methodist community flourished under the leadership of Richard Allen and Absalom Jones. The men, each formerly enslaved, founded the Free African Society to support the needs of fugitives and encourage times of prayer and witness.

At St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, where Allen and Jones worshipped, an upper balcony was built (by black Methodist laborers) to accommodate the growing congregation. When the balcony opened in 1792, black members who attended worship were heedlessly directed upstairs to the gallery, but then forcibly removed from their places during prayer.

Humiliated by their mistreatment, St. George’s black congregants opened Bethel Church in June 1794. Francis Asbury preached at its dedication, and this “house of God,” which became an African Methodist Episcopal Church 20 years later, is still the oldest church property in the country held by African Americans.

But in the year between the balcony humiliation and the glorious founding of Bethel Church, a little-known crisis erupted that revealed the true character of Christian leadership in times of trouble.

As yellow fever engulfed the city, fear spread alongside a plague that ends in hemorrhaging and an overwhelming stench. No surprise that few, if any, were willing to tend to the sick or carry off the dead.

Still, a call went out in the papers to those who might be willing to help. White Philadelphians, including the illustrious physician Benjamin Rush, believed that blacks were immune from the fever. Rush appealed to Richard Allen and Absalom Jones for assistance. In their account of the crisis, the men explain that, after prayer and conversation, they “found a freedom to go forth, confiding in Him who can preserve in the midst of a burning, fiery furnace.”

“Portrait of Absalom Jones” by Raphaelle Peale in 1810. Image courtesy of Delaware Art Museum/Creative Commons

Allen and Jones mobilized Philadelphia’s black community to provide care for the sick and bury innumerable Philadelphians. Initially they worked at their own financial expense, but in time the cost of paying for additional help, not to mention of coffins and hearses, became so great they began to charge for their labor.

The sacrifice among the black community was great. Despite fictions about African vigor and immunity from the disease, black Philadelphians died at the same rate as whites. Still, they served faithfully at the frontlines of the crisis and even among those who had humiliated them. Long after the epidemic had subsided, the black community endured lingering racism and misgivings despite their unparalleled service to the city.

The black community demonstrated the height of what we now hold as an American ideal, no less than a hallmark of religious devotion. They served with selfless love, even caring for those who had insulted their God-given dignity.

It’s a lesson that makes “Contagion” a little harder to screen with equanimity. As one physician said in recent days, it’s really hard to feel like you’re saving the world when you’re watching Netflix from your couch.

RELATED: How to survive a pandemic, spiritually and charitably

The recognition that ours is a nation of diverse people from different cultural and religious backgrounds has polarized our communities for generations. The politics of immigration and a refugee crisis have sharply divided people of faith. And now, even as the federal government has launched initiatives to buttress a flagging economy, we risk losing sight of the most vulnerable among us.

Indeed, based on the example of some of our leaders, we might be tempted to blame others, perpetuating stereotypes associated with the origins of the disease or contribute to the spread of lies on social media that propagate prejudice and discrimination.

Instead, we should look to such models of faith who dedicated themselves to the public good amidst a burning, fiery furnace. The black community in Philadelphia demonstrated the highest ideals of service in their day and, in this, continue to provide an enduring example of the way of love for our own.

(Jeffrey W. Barbeau (@jeffbarbeau) is professor of theology at Wheaton College and author of “The Spirit of Methodism: From the Wesleys to a Global Communion.”)