(RNS) — With prison systems nationally shutting down outside visitation due to the pandemic, one Muslim chaplain is working to help close the gap between incarcerated Muslims and their families.

Founded by former prison chaplain Tricia Pethic, the Muslim Prisoner Project is donating gifts to the children of imprisoned Muslims for the Islamic holiday of Eid al-Fitr, which will mark the end of the holy month of Ramadan in late May.

Many state systems have suspended all visitation, as has the Federal Bureau of Prisons, to stave off the rapid spread of the coronavirus among prisoners confined in cramped quarters, sometimes with deficient healthcare and hygiene.

That has added a new sense of urgency to Pethic’s work.

“Previously you could only see your mother or father once a week,” said Pethic, who formally incorporated the project as a nonprofit last year. “Now you can’t see them at all until further notice. That’s why it’s so critical that we make sure these children know their parents are still thinking about them, especially as Ramadan is coming up.”

RELATED: Click here for complete coverage of COVID-19 on RNS

The Barbie Ibtihaj Muhammad doll. Photo courtesy of Mattel

Last year, Pethic sent gifts to 24 children of inmates at five facilities in New York and New Jersey. This year, the initiative has raised about $17,000, after receiving endorsements from prominent U.S. Muslim figures, including Imam Zaid Shakir, Imam Suhaib Webb, Ingrid Mattson and Sheikh Faraz Rabbani.

Now, the group plans to expand to serve children of inmates at 25 facilities.

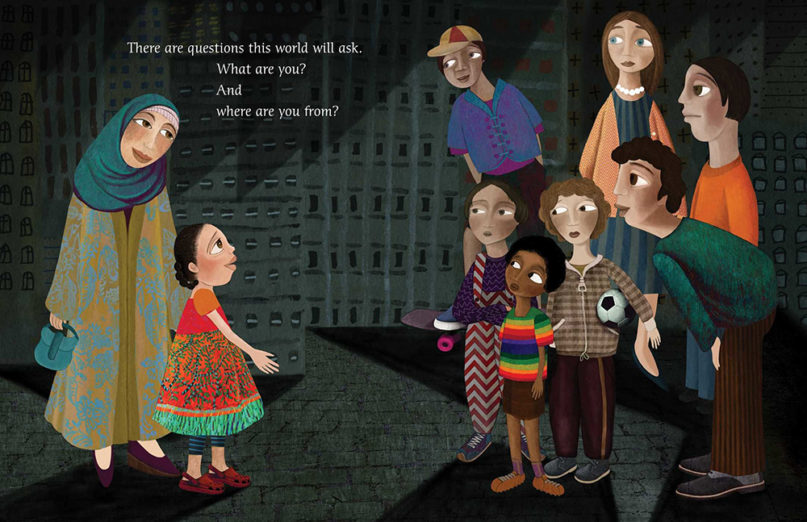

Gifts are customized for each family. Among other items, they distribute Barbie dolls in the likeness of Muslim Olympian Ibtihaj Muhammad, Mark Gonzales’ children’s book “Yo Soy Muslim” and products from Muslim “edutainment” series Rafiq & Friends.

“Mass incarceration has a deep and lasting effect on the children of incarcerated people, which, in turn, has a detrimental impact on our communities,” Rafiq & Friends’ founders, husband-wife duo Justin and Fatemeh Mashouf, said in an email. “We feel that giving children a sense of community, identity and joy is a responsibility and opportunity for us to walk in the prophetic example.”

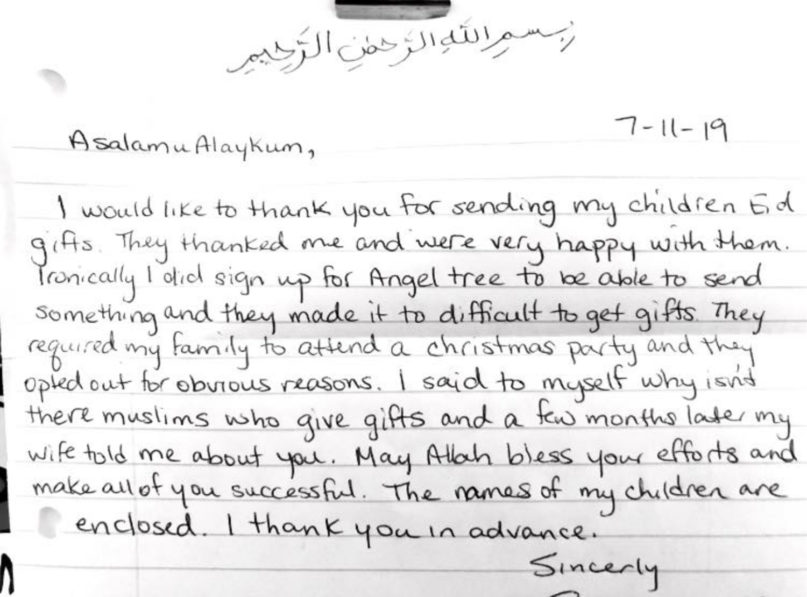

The Eid gift drive, now in its second year, was inspired by the Christian initiative Angel Tree, a family ministry program run by Prison Fellowship to deliver Christmas gifts to inmates’ families.

“Muslim inmates should not have to go to Angel Tree and other Christian organizations to get help,” Pethic said. “We really need to develop comparable services to inmates.”

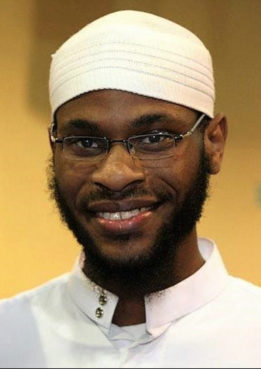

Memphis-based imam Adrian Kirk, who also serves as a prison imam for the faith-based anti-recidivism group ANSAR 101, said Muslims’ attitudes toward incarceration are evolving but are often “uneducated.”

Adrian Kirk. Image courtesy of Muslim Prisoner Project

“Some of them will say things like, ‘If you did the crime, you do the time,’ with no consideration,” he said. “These are human beings. Some of them may have committed crimes, but that doesn’t take away the fact that they still have needs. Their children and families have needs, too.”

Groups like Believers Bail Out, Link Outside and the Tayba Foundation have emerged in recent years to serve incarcerated Muslims. But Kirk said he began volunteering with the Muslim Prisoners Project because of the “incredible uniqueness of the program” within Muslim communities.

“It’s so terribly needed that it shouldn’t be so unique,” Kirk said. “It’s just a no-brainer. It affects us, whether we know it or not. The trauma these kids and their parents face can really impact their character … if they have a community checking in on them, steering them in the right direction, that can really change society.”

Because about 90% of incarcerated Muslims converted to Islam while behind bars, Pethic says she thinks of her work as an interfaith service.

“A lot of families taking care of these prisoners’ children are not Muslim,” Pethic said, noting that she calls each family to ask if they would be willing to accept the gift. “We recognize that not everybody who is receiving gifts and handing these gifts to the children belong to our faith. It’s an introduction, sometimes for the first time, to Islam for the family.”

Besides their annual gift distribution drive, which occurs before Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha each year, the initiative’s main missions are to provide incarcerated Muslims and their chaplains with adequate religious literature — not just pamphlets and donated books with barely coherent English — as well as to serve as a resource for mosques in supporting local incarcerated Muslims.

When Pethic left her job at a women’s facility in New York, she decided to launch the organization to offer resources to Muslim chaplains and inmates, as well as mosques that found themselves unable to assist inmates and formerly incarcerated Muslims seeking assistance.

Tricia Pethic. Image courtesy of Muslim Prisoner Project

Pethic, who lives in Rochester, New York, studied Islamic chaplaincy at Hartford Seminary. As she looked at her specialization options — which included serving in a hospital, university, military or prison — she chose her path on a whim.

“I literally looked at the words ‘prison chaplaincy’ on my screen and I thought, why not?” she said.

But as Pethic began working in detention facilities in Danbury, Connecticut, and Albion, New York, she quickly recognized the critical importance of the job due to the lack of Muslim chaplains and resources to support Muslim inmates.

“Not a lot of Muslims are really thinking about the fact that there’s this whole ‘hidden ummah’ (Muslim community) that we don’t see because they’re not in our prayer ranks,” Pethic said. “But every single day, they get up and they imagine themselves one day being in our prayer ranks. I think if they knew about the sort of unrequited love and desire that’s there, they would just rush into it.”

RELATED: Film follows ‘honest struggle’ of formerly incarcerated Muslims reentering society

A report by the civil rights group Muslim Advocates last year found that about 9% of the state prison population identifies as Muslim. Previous data shows that Muslims make up about 12% of federal inmates, while Muslims make up just 1% of the American population.

Yet those incarcerated Muslims often face serious challenges in receiving religious accommodations, Pethic said. The Muslim Advocates report, which examined 163 Muslim prisoner lawsuits in a 15-month period, found that states’ prison system policies on accommodations are wildly inconsistent. One Muslim prisoner files a federal lawsuit alleging insufficient religious accommodations every three days. Most revolve around access to religious diets, often during Ramadan, or obstacles to prayer and worship.

A thank you letter sent from an inmate whose family received gifts from the Muslim Prisoner Project. Image courtesy of Muslim Prisoner Project

Last week, 20 faith groups led by Muslim Advocates sent a letter to prison administrators urging them to accommodate prisoners’ religious needs during the outbreak, particularly as Ramadan nears.

“We remain deeply concerned that prisons will use this crisis as an excuse to deny basic religious accommodations to prisoners in their care,” the groups wrote.

But a lack of Muslim chaplains, who serve as advocates for Muslim inmates in addition to providing spiritual guidance and leadership, only enables such challenges, Pethic said. In 2009, there were only eight board-certified Muslim chaplains in the entire U.S., according to the Association of Professional Chaplains.

That has left much care of Muslims in need of assistance to interfaith chaplains or volunteer Muslim chaplains.

“It shouldn’t be the case that a prison administrator is scouring to try to find a volunteer from the Muslim community,” Pethic said. “We should be willing to fill that role.”