RALEIGH, N.C. (RNS) — Rachael Wooten wasn’t especially interested in Tibetan Buddhism when she discovered Tara, the female buddha of Tibet, often portrayed as a green young woman seated on a lotus throne.

A native of the small, eastern North Carolina town of Kinston, Wooten grew up Methodist, earned a Ph.D. in psychology and has for years practiced psychotherapy in Raleigh.

But in the early 1990s, shortly after reading a book on cross-cultural expressions of the feminine divine, she became hooked on the sixth-century female deity whose name means “star.”

“I did not set out with the intention for any of this,” said Wooten, 73. “But once I got into it, I didn’t want to leave it.”

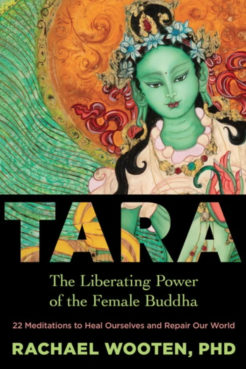

Twenty-seven years later, Wooten has written a book, “Tara: The Liberating Power of the Female Buddha,” in the hopes that the woman, considered a savior figure to many Tibetans, may help Western readers seeking a divine spiritual exemplar in a female form.

Book cover of Wooten’s book, TARA. Courtesy Image

Wooten thinks Tara, with her 21 different emanations or manifestations, belongs to the world beyond Buddhism.

She is eager to teach others how visualizing Tara as she’s often portrayed — sitting on a cushion holding a lotus, her right foot stretched forward as if ready to leap into action — can help quiet turbulent emotions and bring inner peace, especially as people struggle during the current pandemic.

She hopes her book’s practical meditations on Tara’s different emanations can help people overcome suffering and cultivate compassion even if they never embrace Buddhism as their main spiritual practice.

“When you visualize Tara, you’re visualizing this enlightened female buddha whose whole purpose is to help,” Wooten said. “That is our awakened consciousness. When you’re looking at her, it resonates with an inner reality. We have the same awakened subtle energy inside of us.”

For 10 years, Wooten has led a monthly Tara practice in a church in Raleigh, consisting of meditation mantra chanting and personal sharing. (It has recently gone online.)

“I felt an immediate connection to Tara as someone who is grounded and solid and serene but has a foot forward ready to leap to the aid of those who called out,” said Kate Bloedau, 46, of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, who participates in Wooten’s monthly sessions. “That felt like what I wanted to be in the world.”

Bloedau, a nurse, wears a small Tara pendant and said she’s especially drawn to another common rendering, the Orange Tara, who heals illness. She keeps a card with an image of the Orange Tara in her car and often meditates on her when she’s washing her hands, which these days is all the time.

Wooten’s experience with Tara began as she was packing up her Raleigh home before moving to Switzerland to study at the C.G. Jung Institute in Küsnacht, near Zurich. Years of working as a psychotherapist had left her dry, she said, and she had developed an interest in Jungian analysis.

As she was moving furniture in her home, she began to panic.

All of a sudden she began seeing bright flashes of white and green lights.

At first she thought something was wrong with her eyes.

But she had read a book about Tara, which also explored the Black Madonna, the medieval image of the Virgin Mary often used by Catholics and Orthodox Christians as a devotional aid. Then it came to her: The green light she was seeing might be Tara.

A statue of Tara on a windowsill in Rachael Wooten’s study. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

It made sense, as Tara is known for protecting her devotees from fear. Tibetans pray to her in their time of need, just as Catholics pray to Mary for her intercession.

Months later, in Switzerland, Wooten shared her experience with Lodrö Tulku Rinpoche, a Tibetan monk who lives there and who has become her teacher. He listened to Wooten’s story of the green and white lights and told her she had a past life connection to Tara.

“You should take an initiation and do these practices,” he said.

It took her six months to work up the courage. But once initiated to the Green Tara, Wooten found the practice comforting and healing.

“When you do these visualizations and say these mantras, which are well over 1,000 years old, your nervous system will calm down,” Wooten said. “Cortisol levels will drop. People start to think of everyone else they’re worried about. The idea that you could energetically wish them to feel calmer, accompanied, loved, and to benefit from this subtle energy is not unrealistic at all.”

Wooten does not impose Tara teachings on her patients, whom she sees in her study in her Raleigh home. But on their way to the study, they may find a glimpse of eclectic interfaith travels.

The mantelpiece in her living room and the walls around her house attest to multiple sources of spiritual inspiration: Native American feathers, photos of a rabbi who has been a mentor to her, a drawing of Jesus and lots of small statues of female deities.

The shrines reflect her lifelong search for spiritual understanding. Growing up, Wooten would often attend services with her best friend, who was Jewish. Sometimes they’d visit her church, sometimes her friend’s synagogue.

Her brother’s early death from leukemia and a divorce in her early 30s prompted her further along her path. After joining a liberal Baptist church in Raleigh, she took an interest in Matthew Fox, theologian and former Catholic priest. His interest in ecological and environmental movements influenced Wooten’s exploration of Native American spirituality, which led to training in indigenous ceremonies.

Since starting her Tara practice, Wooten, who does not consider herself exclusively Buddhist, has continued to explore other faiths, especially Judaism. For many years, before his death in 2014, she corresponded with Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, one of the founders of the Jewish Renewal movement and an innovator in ecumenical dialogue.

Richard Jaffe, a professor at Duke University who studies Buddhism, said that fits squarely within the religion’s ever-growing Western adaptation.

“There’s no particular creed or profession of faith one needs to accept to practice Buddhism,” Jaffe said. “It’s not exclusivist in any way. It’s quite open and acceptable.”

Finding comfort and healing through Tara without taking on the whole foundation of Buddhism is increasingly the way people live their faith. Nearly all Americans — of all religious faiths and no religious faith – say they meditate at least once a week, according to a recent Pew Research survey. More than 36 million Americans practice yoga. “Religious mixing” or syncretism has been around for decades.

“The practices are incredibly portable,” said Wooten. “I want people to see, ‘I can use this practice that can really help me out, and I don’t have to move away from anything I’m already connected to that is already precious to me, that already makes sense to me.’”

Though it might make sense, Wooten emphasizes that we need to access a reality that is beyond the rational.

“We can’t think our way to most of our deepest problems,” she said. “We just can’t.”