(RNS) — It had to happen during COVID-19, and it did, all over again.

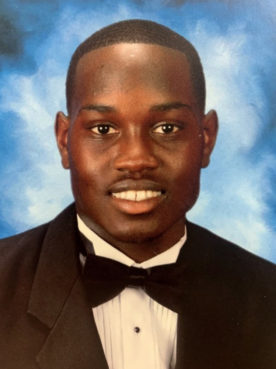

Nearly three months ago now, Ahmaud Arbery was followed, cornered and killed by two armed white men with shotguns in their pickup truck — a former cop and his son — while he was out jogging on a bright afternoon through a local neighborhood two miles from his own home. He was 25 years old. The case is currently on its third prosecutor, and Ahmaud’s killers were only arrested after a video of the killing surfaced online and revealed Ahmaud’s death for what it was — the lynching of a black man in 2020.

It made me painfully wonder again, as it always does, what do other white people, and especially white Christians, really think about these things? Are they quietly for it or against it? How much do they even personally care, and, if they do care, will they speak out — especially to other white people? Will white people ever decide that such monstrosities must never be allowed to happen again? On a deeper level, even if most would quickly and sincerely say they are against it, do white people still find these continual lethal killings of black bodies and lives tolerable, or do they think it’s impossible to change?

Until enough white people find the brutalizing and killing of black people by white people — including police — intolerable and unacceptable and necessary to change, it will go on and on and on.

After these regularly recurring events in the U.S., I painfully and with diminishing hope, listen to what white churches and people say or don’t say. Of course, black pastors and churches, after Ahmaud, grieved and mourned, fell into exhausted anger and wailing and lamented how utterly weary they are of these things happening to them and their children in a society that has such little commitment to protect them from ugly, sinful and violent racism. This week, I shared with our whole Sojourners list the most brilliantly and painfully articulated sermon and film footage called The Cross and the Lynching Tree: A Requiem for Ahmaud Arbery by Rev. Dr. Otis Moss III from Trinity United Church of Christ. It was a brilliant articulation of what true Christian faith means in the most dramatic contrast to the counterfeit faith of many white Christians who have submitted and lost their faith to America’s Original Sin.

Ahmaud Arbery, in an undated family photo. Courtesy photo

Fortunately, there were some white Christian leaders, including a handful of white evangelicals, who raised their voices — though not nearly enough of them. Russell Moore of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, evangelist and Bible teacher Beth Moore, Nick Hall, a board member of the National Association of Evangelicals, and Christian conservative lawyer and writer David French were among those who made strong statements after the damning video became national news. Gratefully, a number of mainline denominational and multi-cultural churches, like our young millennial District Church in Washington, D.C., noted the horribly hateful act in their time of prayer. As far as I know, none of Donald Trump’s most famous evangelical supporters and advisers said a word.

Once again, it took a horrific, graphic video to bring this killing into the broader national discourse and to the attention of white America. Yet again, there is always the temptation to conclude that the destruction of black lives by white people will be chalked up to “isolated” and “tragic” “incidents” rather than a broader pattern in which black lives and bodies are treated as having low value or no value by white people and the systems we have created and maintained — including by us as white Christians.

Indeed, just three weeks later, we saw that in the case of Breonna Taylor, a young black EMT gunned down while in bed in her own home on March 13 by police who were searching for a suspect they already had in custody — a killing that was not captured on video. This time, the outcry among white Christians was far more limited and muted, especially outside of the Louisville area.

Unfortunately, these killings aren’t the only ways we see the devaluing of black bodies in the U.S. today.

The COVID-19 pandemic has now laid bare what is still “acceptable” to white America, including many white churches. The unequal suffering of this plague has been verified by the statistics. We’ve seen the tragic, ghastly evidence mount day by day and week by week that COVID-19 is infecting and killing people of color at vastly disproportionate rates. We’ve talked about the clear relationship between the racist structures of U.S. society, the economic and health disparities they create, and the subsequent increased vulnerability of communities of color to the virus. And now we need to talk about how many white people, including many who would call themselves followers of Jesus, are treating black and brown lives in the debate over “reopening.”

Many of the dynamics of the current debate over reopening, though rarely stated this way, ultimately boil down to a simple question: Whose lives are many white people, including white Christians, willing to risk in order to get their lives and the economy back to some hopefully imagined “normal”?

Sadly, far too many of our country’s leaders are presenting the country and our states with a false binary choice between protecting public health and restarting the economy. The reality is that there will be no real and long-lasting recovery without mitigating and ultimately containing this pandemic. In the midst of the necessary efforts to protect lives, we must also do much more to help those who have been worst hit economically.

People wait for a distribution of masks and food from the Rev. Al Sharpton on April 18, 2020, in the Harlem neighborhood of New York after a new state mandate was issued requiring residents to wear face coverings in public due to the coronavirus. An Associated Press analysis of available data shows that nearly one-third of those who have died from the coronavirus were African American, even though blacks are only about 14% of the population. (AP Photo/Bebeto Matthews)

A revealing article in The Washington Post about a shopping center in the suburbs of Atlanta provides an incredibly troubling (if anecdotal) answer. Part of the attitudes of the wealthy white shoppers thrilled to be out in the world again seemed to stem from a lack of proximity to people affected by the pandemic. One man put it this way, “It’s a personal choice … If you want to stay home, stay home. If you want to go out, you can go out … I don’t know anybody who’s got (COVID-19).”

Left out of his statement and perhaps his behavior is any consideration for those to whom he might transmit the disease if he gets infected without ever getting sick himself.

Another man was more direct about his COVID-19 calculus: “When you start seeing where the cases are coming from and the demographics — I’m not worried.” As the article had earlier made clear, the county where this shopping center is located has seen 3,600 confirmed cases and more than 150 deaths from the virus, but mostly in the poorer and more heavily black part of the county closer to Atlanta. In other words, for these shoppers, the lives of black people, of poor people, old people and of sick people are the lives they are willing to risk. The attitudes of the shoppers stand in such stark contrast to those of the store clerks in the story who, unlike many of the shoppers, are wearing masks and feeling nervous or afraid, having to choose between their lives and their livelihood.

Some insight about the big divide in U.S. society that was there before COVID-19 but is now more exposed came from conservative New York Times columnist Bret Stephens. He described the divide between those in society who are “remote” and those who are “exposed”— those for whom “physical presence is a job requirement” and who represent as much as 63% of the out-front workforce in America. Unfortunately, far too many of the policy decisions, including many decisions guiding “reopening,” are being made by those who are relatively remote from the risks involved. It has become clear that “remote” means privileged and safe, and “reopening” threatens a less safe work force.

Another writer, Michele Norris, recently wrote in The Washington Post in response to the armed and overwhelmingly white anti-lockdown protesters in my home state of Michigan and elsewhere. After pointing out the obvious, that black protesters who showed up heavily armed in public spaces, like these white protesters, would be arrested en masse, or worse, Norris stated that “accepting the display of firearms at protests by some and not others means that we must also accept that some are rewarded with a kind of special citizenship that allows them to be seen as patriotic instead of threatening, and aggrieved instead of aggressive.”

To me, these protesters represent a more extreme but not fundamentally different version of the white shoppers in Georgia, and it does not feel like a coincidence that these astro-turf protests gained steam as the data on infections and deaths continued to confirm the virus’s racially disproportionate impact.

We want to reopen our society but in the most safe and protective ways possible — for all of us. It is wrong, monstrously wrong, for white shoppers to place service workers and, by extension, broader communities disproportionately made up of people of color at risk through the act of shopping without a mask or safe distancing. The protesters are demanding, with the implicit threat of violence their large guns bring, that they be allowed to risk the lives of black and brown people. Unacceptable.

COVID 19 will also reveal our faith, what is acceptable and unacceptable to us, what is impossible or necessary now to change, or whether our neighbors and brothers and sisters in Christ include those who look different than we do.

Jim Wallis. Courtesy photo

Ahmaud should have been protected in his society, as his mother painfully said. The many people affected by COVID-19 should be protected, too. So, is America ready to protect all its black and brown people who are most at risk — or not?

(The Rev. Jim Wallis is president of Sojourners. His new book Christ in Crisis: Why We Need to Reclaim Jesus is available now. Follow Jim on Twitter @JimWallis. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)