“Our Lady of Ferguson and All Killed by Gun Violence” by Mark Doox in 2019. Image courtesy of Mark Doox

(RNS) — In the New Testament’s Letter to the Ephesians, Paul writes, “For we wrestle not against flesh and blood” — or race? — “but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world.” Could these things that Paul opposes be ideas and systems of human oppression that deny the knowledge of a God of justice and love?

In this time of mass protest and reexamining of America’s racial past and present, I’ve been thinking about art and especially how Christian images can contribute to, or hinder us from, processing our national discourse about social justice and Black Lives Matter.

I am African American. I make Byzantine-influenced icons. Taking a cue from the jargon of Orthodox Christians, I like to call myself an “iconographer.”

I have a passion for traditional icons, which are supposed to give the viewer a glimpse into the spiritual realm and the kingdom of God. Though I have embraced modern innovations, the idea of seeing into invisible realms and “what’s really going on” still motivates me.

I started painting traditional icons more than 30 years ago as a novice monk in a Russian-affiliated Orthodox monastery in company with mostly American converts to the faith. At 29 years old, having already attended art school, I was on a spiritual journey to find God and myself. My first icon was one a visiting iconographer had left incomplete, tucked away in the corner of the monastery’s chapel, filled with icons of the typical Orthodox pantheon of saints, angels and, of course, both Jesus and Mary.

After about a year there, now bound for San Francisco, I left the monastery, convinced I didn’t have a vocation to be a monk. Instead, I felt I had found another vocation: to paint icons.

RELATED: How Jesus became white — and why it’s time to cancel that

In the years that followed, I was given spectacular opportunities. I painted a grand icon mural for St. Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church in San Francisco of 60 oversized saints led in a dance by an olive-skinned Christ. I have painted numerous icons of Black Christ for St. John Coltrane A.O.C. (African Orthodox Church), also in San Francisco, whose patron saint is the jazz great John Coltrane.

There came a point when I realized something about how we allow our sacred images to function. Among other things, they relocate the power and spiritual glory of those they depict to our preferred racial group.

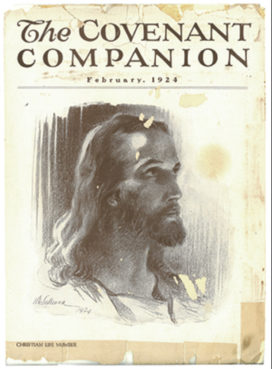

“The Covenant Companion” cover in 1924, featuring a Warner Sallman sketch of Jesus. Image via covenantcompanion.com

This eventually led me to forsake liturgical icons and to start creating icons that emphasized this weakness in our sacred images, which have been steeped in American divisions of race and power. In effect, I began to paint iconoclastic icons.

My reasons were not political, though I know my icons had political ramifications. Instead I wished to stay close to my original calling of making icons that mattered and that drew the viewer closer to reality and God.

In 1923, the founders of a small denominational magazine called The Covenant Companion needed a cover for their first issue. Their art director, a little known Chicago commercial artist named Warner Sallman, drew a pencil sketch of Jesus as a light-haired European, which first appeared in 1924. That white Jesus (and he was very white indeed) became the most famous image of Jesus in the U.S. and maybe the world.

Why? I believe that the image was there in the societal landscape of America waiting to be brought forth. The image expressed something already hoped, desired, perceived and believed. Sallman just gave form to it.

Jesus Christ is the icon of icons. In my artistic evolution, I’ve found a few biblical passages helpful concerning the image of Christ. Isaiah, the Hebrew prophet, said in a song that is often taken as a foretelling of Christ’s appearing, “He had no beauty or majesty to attract us to him, nothing in his appearance that we should desire him.”

In Paul’s Letter to the Corinthians, he wrote, “But God chose the foolish things of the world to shame the wise; God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong. God chose the lowly things of this world and the despised things — and the things that are not — to nullify the things that are, so that no one may boast before him.”

These are not Scriptures that can be used to state white supremacy or even white privilege. Can we say the same for the Sallman image and its “white man is God” tone? Would replacing the Sallman image with a chocolate-covered version of Jesus be different? Would a good-looking Hollywood version with an Afro (or dreadlocks) be better?

“Son Of Man (After Magritte)” by Mark Doox in 2019. Image courtesy of Mark Doox

In my opinion, neither image is better than the other, nor does either express the real message of Christ and God’s love. A war of ethnic Christs won’t bring humanity closer together in empathy or love.

Over the years, these ideas have led me to approach my icons and the image of Christ differently and have decidedly transformed my image making. I have combined my primary influence, the Byzantine iconographic genre, with early Italian religious iconography and specific ideas found in the 20th century dada, pop and surrealist artistic movements.

I find the need to somehow touch on the Scriptures mentioned above — that something is what I call “the N-word of God.” I find the N-word of God in the same Jesus who said, “ … inasmuch as you did it to one of the least … you did it to me.” And we know, in America, no one is less than the N-word.

And there is significance in the N-word of God.

The significance of he who is lynched and hanging on a cross.

That is where, I believe, our real Christian transformation and empathy lies — in the cross of Christ. Not in the exaltation of white or Black flesh or their images. Nor the cliché “I don’t see color,” because we all do. But the empathic principle of seeing many hues yet still our common humanity, a denial of otherness, a thirst for justice and a firm rejection of “might makes right.”

(Mark Doox, an internationally exhibited artist, is the ordained iconographer of the celebrated Coltrane Church. His gallery art, prints and illustrations for his graphic-literature novel-in-progress can be seen at markdoox.com. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

But, of course, producing this journalism carries a high cost, to support the reporters, editors, columnists, and the behind-the-scenes staff that keep this site up and running. That's why we ask that if you can, you consider becoming one of our donors. Any amount helps, and because we're a nonprofit, all of it goes to support our mission: To produce thoughtful, factual coverage of religion that helps you better understand the world. Thank you for reading and supporting RNS.