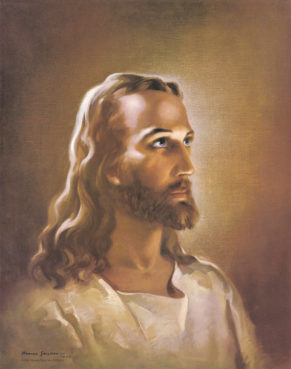

Painting by Warner Sallman, “Head of Christ,” © 1941 Warner Press Inc., Anderson, Indiana. Used with permission

CHICAGO (RNS) — The first time the Rev. Lettie Moses Carr saw Jesus depicted as Black, she was in her 20s.

It felt “weird,” Carr said.

Until that moment, she’d always thought Jesus was white.

At least that’s how he appeared when she was growing up. A copy of Warner E. Sallman’s “Head of Christ” painting hung in her home, depicting a gentle Jesus with blue eyes turned heavenward and dark blond hair cascading over his shoulders in waves.

The painting, which has been reproduced a billion times, came to define what the central figure of Christianity looked like for generations of Christians in the United States — and beyond.

For years, Sallman’s Jesus “represented the image of God,” said Carr, director of ministry and administrative support staff at First Baptist Church of Glenarden in Maryland.

When she grew up and began to study the Bible on her own, she started to wonder about that painting and the message it sent.

“It didn’t make sense that this picture was of this white guy,” she said.

RELATED: We can’t cancel ‘white Jesus,’ but we can keep telling our church’s story (COMMENTARY)

Carr isn’t the first to question Sallman’s image of Jesus and the impact it’s had not only on theology but also on the wider culture. As protesters around the United States tear down statues of Confederate heroes and demand an accounting for the country’s long legacy of racism, some in the church are asking if the time has come to cancel so-called white Jesus — including Sallman’s famed painting.

Modest beginnings

The “Head of Christ” has been called the “best-known American artwork of the 20th century.” The New York Times once labeled Sallman the “best-known artist” of the 20th century, despite the fact that few recognized his name.

“Sallman, who died in 1968, was a religious painter and illustrator whose most popular picture, ‘Head of Christ,’ achieved a mass popularity that makes Warhol’s soup can seem positively obscure,” William Grimes of the Times wrote in 1994.

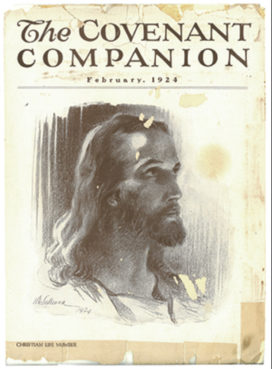

“The Covenant Companion” cover in 1924, featuring a Warner Sallman sketch of Jesus. Image via covenantcompanion.com

The famed image began as a charcoal sketch for the first issue of The Covenant Companion, a youth magazine for a denomination known as the Swedish Evangelical Mission Covenant.

Sallman, who grew up in the denomination, which is now known as the Evangelical Covenant Church, was a Chicago-based commercial artist. Wanting to appeal to young adults, he gave his Jesus a “very similar feeling to an image of a school or professional photo of the time making it more accessible and familiar to the audience,” said Tai Lipan, gallery director at Indiana’s Anderson University, which has housed the Warner Sallman Collection since the 1980s.

His approach worked.

The image was so popular that the 1940 graduating class of North Park Theological Seminary in Chicago commissioned Sallman to create a painting based on his drawing as their class gift to the school, according to the Evangelical Covenant Church’s official magazine.

Sallman painted a copy for the school but sold the original “Head of Christ” to religious publisher Kriebel and Bates, and what Lipan calls a “Protestant icon” was born.

“This particular image of Jesus met the dawn of the ‘Mad Men,’ of the marketing agency,” said Matthew Anderson, affiliate professor of theological studies at Concordia University in Montreal.

The image quickly spread, printed on prayer cards and circulated by organizations, missionaries and a wide range of churches: Catholic and Protestant, evangelical and mainline, white and Black.

Copies accompanied soldiers into battle during World War II, handed out by the Salvation Army and YMCA through the USO. Millions of cards produced in a project called “Christ in Every Purse” that was endorsed by then-President Dwight Eisenhower and Trump family pastor Norman Vincent Peale were distributed all around the world.

The image appeared on pencils, bookmarks, lamps and clocks and was hung in courtrooms, police stations, libraries and schools. It became what scholar David Morgan has heard called a “photograph of Jesus.”

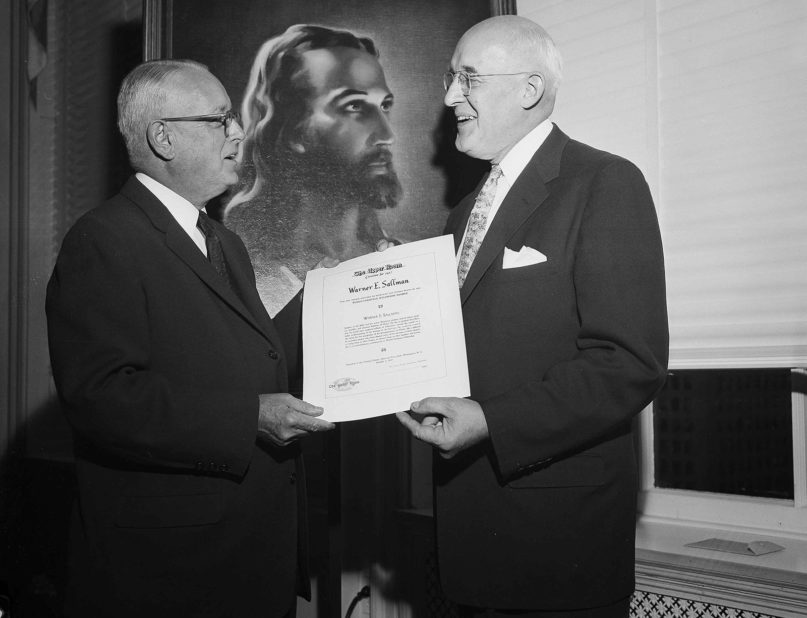

The Rev. J. Manning Potts of Nashville, Tennessee, left, presents the 1957 Upper Room Award for World Christianity Fellowship to artist Warner Sallman of Chicago at a dinner meeting of church and government officials on Oct. 3, 1957, at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. Sallman was honored for his “Head of Christ” painting, shown in background. (AP Photo/Bob Schutz)

Along the way, Sallman’s image crowded out other depictions of Jesus.

Anderson said that it has been common for people to depict Jesus as a member of their culture or their ethnic group.

“If a person thinks that’s the only possible representation of Jesus, then that’s where the problem starts,” he said.

Morgan, professor of religious studies at Duke University in North Carolina, agrees. Some of the earliest images of Jesus showed him “with very dark skin and possibly African,” he said.

RELATED: The N-word of God: Envisioning the image of Christ (COMMENTARY)

Sallman wasn’t the first to depict Jesus as white, Morgan said. The Chicagoan had been inspired by a long tradition of European artists, most notably Frenchman Leon-Augustin Lhermitte.

But against the backdrop of U.S. history, of European Christians colonizing Indigenous lands with the blessing of the Doctrine of Discovery and enslaving African people, Morgan said, a universal image of a white Jesus became problematic.

“You simply can’t ignore very Nordic Jesus,” he said.

Cancel white Jesus

The backlash to Sallman’s work began during the civil rights movement, when his depiction of a Scandinavian savior was criticized for enshrining the image of a white Jesus for generations of Americans.

That criticism has been renewed recently amid the current national reckoning over racism sparked by the death of George Floyd, a Black man killed in an encounter with police.

Earlier this week, activist Shaun King called for statues depicting Jesus as European to come down alongside Confederate monuments, calling the depiction a “form of white supremacy.”

Hugo- and Nebula Award-winning science fiction author Nnedi Okorafor echoed that sentiment on Twitter.

“Yes, ‘blond blue-eyed jesus’ IS a form of white supremacy,” she tweeted.

Yes, “blond blue-eyed jesus” IS a form of white supremacy.

— Nnedi Okorafor, PhD (@Nnedi) June 23, 2020

Anthea Butler, associate professor of religious studies and Africana studies at the University of Pennsylvania, has also warned of the damaging impact of depictions of white Jesus.

“Every time you see white Jesus, you see white supremacy,” she said recently on the Religion News Service video series “Becoming Less Racist: Lighting the Path to Anti-Racism.”

Anthea Butler. Courtesy photo

Sallman’s Jesus was “the Jesus you saw in all the Black Baptist churches,” Butler told RNS in a follow-up interview.

But Sallman’s Jesus did not look like Black Christians, according to the scholar. Instead, she said, Jesus looked “like the people who were beating you up in the streets or setting dogs on you.”

That Jesus sent a message, Butler said.

“If Jesus is white and God is white,” she said, “then authority is white.”

Edward J. Blum, who co-authored the 2014 book “The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America,” said many Christians remain hesitant to give up the image of white Jesus. He believes the continued popularity of white depictions of Jesus are “an example of how far in some respects the United States has not moved.”

”If white Jesus can’t be put to death, how could it possibly be the case that systemic racism is done?” Blum said. “Because this is one that just seems obvious. This one seems easy to give up.”

Jemar Tisby, whose 2019 book “The Color of Compromise: The Truth About the American Church’s Complicity in Racism” appeared on The New York Times bestseller list this week, said that believing in a white Jesus “denigrates the image of God in Black people and other people of color.”

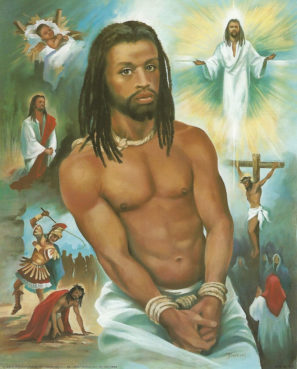

Vincent Barzoni’s “His Voyage: Life of Jesus.” Image via blackartdepot.com

Tisby said that depicting Jesus as only white has theological implications. It narrows Christians’ understanding of Jesus, he said.

“To say that Jesus is Black — or, more broadly, to say that Jesus is not white — is to say that Jesus identifies with the oppressed and that the experience of marginalized people is not foreign to God, but that God is on the side of those who, in Matthew 25, Jesus refers to as ‘the least of these,’” he said.

Still, Tisby is hopeful, pointing to a number of diverse images of Jesus that offer alternatives to Sallman’s.

A decade after Sallman painted his “Head of Christ,” Korean artist Kim Ki-chang created a picture cycle of the life of Christ in traditional Korean clothing and settings, featuring figures from Korean folk religion.

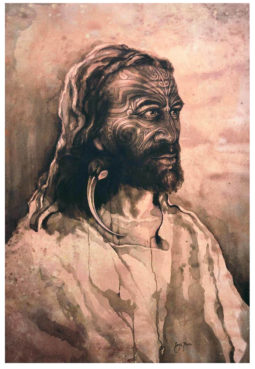

“Māori Jesus” is artist Sofia Minson’s depiction of the Messiah as tangata whenua (indigenous Māori) with full-face moko (traditional tattoo). Image via newzealandartwork.com

More recently, Sofia Minson, a New Zealand artist with Ngāti Porou Māori, English, Swedish and Irish heritage, reimagined Sallman’s Jesus as an Indigenous Māori man with a traditional face tattoo.

And there are numerous popular depictions of Jesus as Black.

Vincent Barzoni’s “His Voyage: Life of Jesus,” depicts Jesus with dark skin and dreadlocks, his wrists bound, while Franciscan friar Robert Lentz’s “Jesus Christ Liberator” depicts Jesus as a Black man in the style of a Greek icon.

Janet McKenzie’s “Jesus of the People,” modeled on a Black woman, was chosen as the winner of the National Catholic Reporter’s 1999 competition to answer the question, “What would Jesus Christ look like in the year 2000?”

“I don’t know that there’s one depiction that is coming to the fore, and that, I think, is illustrative that people are resisting a monolithic vision of Jesus’ embodied self and, and understanding that his very incarnation — the fact that God became a human being in itself — is a way of identifying with all peoples everywhere,” Tisby said.

These days, Carr said, she tries to avoid locking Jesus into one image.

She’s also more concerned about how Jesus is represented in the lives of Christians — rather than in a piece of art.

“It’s not so much the picture and my question about who Jesus is,” she said. “It’s more really the picture of who I look across the aisle and see as representing a different Jesus.”