(RNS) — Last week NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell announced that the league would play the hymn “Lift Every Voice and Sing” before its first games on Sept. 10 as a recognition of racial injustice. To do so would be sacrilege.

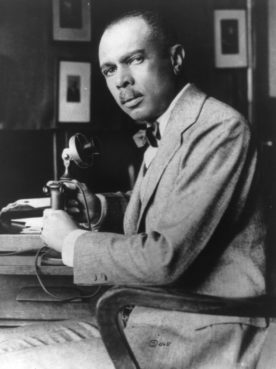

For those unfamiliar with the song, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” — often called the “Black national anthem” — is one of the most widely shared sacred artifacts in the African American experience. Its lyrics were written in 1900 by activist, author and educator James Weldon Johnson, who enlisted his brother, composer and musician J. Rosamond Johnson, to set it to music.

Of course there is no official “Black national anthem.” It is an affectionate nickname, and an old one: It was formerly known as “the Negro national anthem” or “the Negro national hymn.” I have attended events where African Americans have chosen to sing both “Lift Every Voice and Sing” and “The Star-Spangled Banner” after pledging allegiance to the flag.

Johnson wrote the poem for his students in Jacksonville, Florida, to use in a celebration of Abraham Lincoln, then still an affirmed hero of African American history. Despite the rising hammerlocks of Jim Crow, African Americans in 1900 were looking forward to pressing on to a better day. Educating their children — 90% of whom were taught by Black teachers like Johnson — was a key way of preparing them, in the words of my grandmother, a woman whose own mother was born a slave, “to be ready when the doors are opened.”

James Weldon Johnson portrait at desk with a telephone, between 1900 and 1920. Photo courtesy of LOC/Creative Commons

For Lincoln’s birthday, according to Johnson, “the song was taught to and sung by a chorus of five hundred colored school children.” After the Johnson brothers moved to New York, they discovered that those 500 children, many of whom had moved north themselves, had not only kept singing the song but “they became teachers and taught it to other children.”

Churches pasted the song into their hymnbooks throughout the South and during the Great Migration it had been carried northward. It bloomed along with African American consciousness in the Harlem Renaissance. (For a full history of the hymn, see Julian Bond and Sondra Kathryn Wilson’s “Lift Every Voice and Sing: A Celebration of the Negro National Anthem.”)

The song came to be sung wherever Black Americans gathered, in the organizations and institutions where they controlled the space, the narratives and the programming. Very often the song is still sung in spaces Black people actually own — their churches, their clubhouses and their fraternal lodges.

Johnson made “Lift Every Voice” the official song of the NAACP, the organization he served from 1917 until his death in 1938. The song is now a staple of celebrations of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday.

The song is an instruction for activism — “Lift every voice and sing!” It’s a reminder to pay attention to history and to learn the lessons of strength, struggle, faith and hope: “Stony the road we’ve trod; Bitter the chastening rod. … ” It is an invocation and benediction for the struggle; its third verse is a prayer about maintaining the spiritual relationship in a specialized African American salvation history. “God of our weary years, God of our silent tears/Thou who has brought us thus far on the way.”

The song is embedded in liturgies and theological writings, providing the titles for two of the most prominent books in African American biblical studies — “Stony the Road We Trod: African American Biblical Interpretation” and “Yet With a Steady Beat: Contemporary U.S. Afrocentric Biblical Interpretation.” A significant volume of constructive liberation theology is titled “Lift Every Voice: Constructing Christian Theologies from the Underside.”

The song is also liable to be a flashpoint for Black and white misunderstanding. As one of the few Black people I know who listens carefully to white bigots on talk radio, I’ve occasionally heard right-wing radio hosts declare open season on “Lift Every Voice and Sing” and what they thought about “our” song. The vitriol poured out against the song is a cipher for the vitriol directed at Black people.

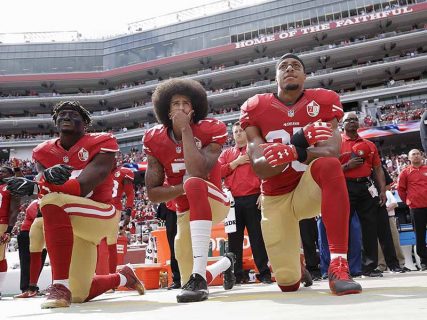

In this Oct. 2, 2016, file photo, from left, San Francisco 49ers outside linebacker Eli Harold, quarterback Colin Kaepernick and safety Eric Reid kneel during the national anthem before an NFL football game in Santa Clara, California. (AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez, File)

NFL stadiums are white-owned spaces where cultural battles over the U.S. national anthem have already exposed our culture’s racial hatred, predatory power and institutional domination. “Lift Every Voice and Sing” is too sacred to be trotted out for public consumption at any such popular bread and circus event controlled by white “owners.”

“Lift Every Voice and Sing” shouldn’t be desecrated as part of the NFL’s ongoing, misplaced attempt to apologize for its exclusion and mistreatment of Colin Kaepernick and its general misunderstanding of players’ protests against racism. The song shouldn’t be used to paper over the current conflicts over statues that are the idols of white supremacy. Black Americans must assert the sacredness of “Lift Every Voice and Sing” and resist its being insulted by bigots with a heritage of African American blood on their hands.

It’s long been said that football and other professional sports are rites of popular civil religion. Perhaps it can be used to reshape the nation, weave a better tapestry, a more perfect union, that is anti-racist, just and equitable. Let that civil religion have its own songs, however. Decontextualizing “Lift Every Voice and Sing” for profane, public purposes is not the way to go.

(Cheryl Townsend Gilkes is an assistant pastor for special projects at the Union Baptist Church in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Professor of African American Studies and Sociology at Colby College. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)