(RNS) — They can’t shake hands. They can’t sing robustly. And, in most cases, they can’t worship in person with people they’ve seen on a weekly basis for years.

Clergy have been forced to adjust to a “new normal” of leadership in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, a crisis that was unexpected both at its start and in its continuing duration.

“We moved from snow day mentality to marathon mentality now,” said the Rev. Rob Dyer, senior pastor of a Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) congregation in Belleville, Illinois.

Clergy are beginning to accept that many congregants won’t darken their doors anytime soon. That’s either because they’ve decided not to reopen for a while or, if they have reopened, they are seeing fewer attendees due to new restrictions and fears of contracting the coronavirus.

RELATED: Click here for complete coverage of COVID-19 on RNS

A recent Barna study found that two months ago no church leaders planned to wait to reopen until 2021. By mid-July, 5% said that was their plan.

Overall, faith leaders are dealing with a mix of angst, grief and fatigue, even as they try to be innovative in how they minister to people amid the uncertainty.

Dyer, who led a mid-July webinar for consulting group Ministry Architects on the topic of whether to reopen, joked that he “skipped pandemics” in seminary as he guided dozens of participants who tuned in for advice.

“It is an unprecedented time,” he said, acknowledging how unprepared anyone was for these circumstances. “I hope you’re in a church where people give you some grace and if you’re not, I hope you have friends and family that give you some grace. Because these are hard decisions. But I think if people know you love them and you really just want the best for them, I think we can access a lot of grace through this situation.”

Religion News Service spoke with leaders from different faiths and locations across the country about how their professional lives have changed in recent months and how they are coping.

One rabbi summed it up this way: “I think most people who go into the clergy, which is so much based on interaction and personal relationship, didn’t sign up for a world in which that is taking place in a virtual forum at a distance.”

Here are four of their stories:

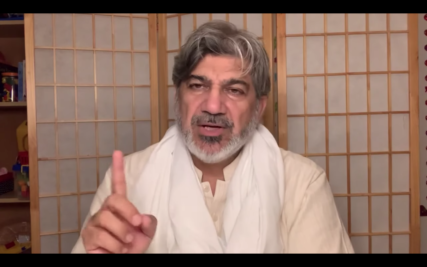

Imam Naeem Baig, leader of Dar Al-Hijrah Islamic Center in Falls Church, Virginia

For the leader of this suburban Washington mosque, it’s the basics of congregational life that have been missing, even now as the mosque has begun reopening gradually over the last few weeks.

“The whole month of fasting we had to keep the mosque closed,” Baig said. “And right after the month was over, the day of Eid, that celebration did not happen.”

Imam Naeem Baig speaks on lessons from Ramadan in a YouTube video for Dar Al-Hijrah Islamic Center. Screenshot from the video

After Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr, with the loosening of restrictions in Virginia, his Islamic center first opened for private prayers, then asked people to register a maximum of 90 cars at a time for Friday prayers in the parking lot. Now, a limited number can meet inside for Friday prayers, no longer shoulder to shoulder but in designated spots where they lay a prayer rug they must bring with them.

“We came up with all of these new ways of still creating the sense of community but finding a way to still keep that human spirit alive of belonging, of loving, of the community, of taking care of one another,” Baig said. “But it was difficult. Obviously, you cannot hug someone anymore. You cannot shake hands with the people anymore. You are wearing a mask and you cannot see each other’s smile anymore.”

He and other leaders of the mosque used Zoom to not only share sermons but to play games such as Kahoot! and Pictionary for intergenerational activities. They also offered a cooking competition.

“We came up with these ideas to engage people: Who’s cooking what?” he said, laughing as he recalled it. “We were asking people to vote online to select which dish looks the best.”

Baig, 57, is also a Clinical Pastoral Education student. He said it has been a source of strength to hear from his chaplaincy program supervisor as well as other students — pastors and other clergypersons — about the new activities they are trying with their congregations.

A volunteer chaplain at a hospital, Baig had to use FaceTime to connect with COVID-19 patients — including one who later died — and their families. Funerals, likewise, have been from a distance, with no hugging allowed.

But one bright moment occurred when he was permitted to enter a hospital, after a mother requested an imam be present when the traditional call to prayer is spoken near a baby’s right ear for the first time.

“I was very happy that the hospital was able to make arrangements,” said Baig, who said he was “fully covered” as he stood near the “fully protected” baby. Though he was not able to hold the child as he normally would, he said nurses joined the mother and father for the emotional moment. “It was very beautiful.”

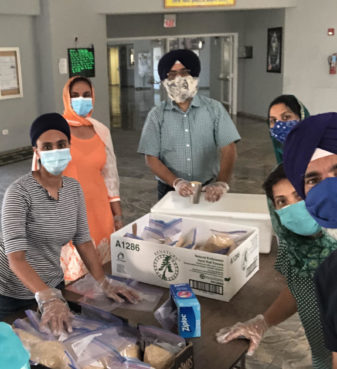

Jasvir Kaur Singh, community activist and a leader of Sikh Religious Society, Chicago

A community activist at her gurdwara, or house of worship, in Palatine, Illinois, Singh said the pandemic is reshaping her view of herself as a “people person.”

Jasvir Kaur Singh, left, packs boxes of food for a pantry with other members of her gurdwara, a Sikh house of worship in Palatine, Illinois, during COVID-19. Courtesy of Jasvir Kaur Singh.

The congregation leader has had to adjust from in-person meetings and going to her gurdwara a few times a week to being home most of the time, working the phones and using Zoom as she seeks to fulfill the needs of hungry residents in Chicago and the northwestern suburb of Palatine.

“I think body language and physically being in person speaks so much that you don’t have to do some of the explaining,” Singh, 46, said of the conferencing that she admitted can be mentally exhausting. “Via Zoom, it’s so much more difficult.”

As one of the organizers of the Sikh society’s COVID-19 response, she has helped transform the langar, a communal meal usually hosted by families of the gurdwara for as many as 1,000 worshippers and visitors on Sundays. Teams of people have instead prepared 275 to 300 meals and transported them an hour away to the Salvation Army to provide biryani, a rice-and-vegetables dish, to homeless people.

She’s also been contacting local pantries to coordinate replenishing them with dry goods.

But she admits the work can be tough sometimes.

“You get overwhelmed,” said Singh. “Who do we help? ’Cause there’s so many people asking for help and you want to help them all.”

She has used meditation to cope with the stress.

“Instead of five, 10 minutes, I’ll do 20 minutes in the morning to kind of refocus,” Singh said, “so I can function much more effectively.”

Sometimes, she said, the load has been lifted by the young adults in her congregation who, many of them home from college, pitched in, offering to deliver groceries or food prepared at the gurdwara for elderly members and Indian families stranded due to COVID-related travel restrictions.

“I guess the positive of this is that a lot of Sikh youth usually don’t come to gurdwara,” she said. “They were the ones we needed because I didn’t want the 65-or-older, high-risk people going out to make deliveries to people’s homes.”

RELATED: As pandemic wears on, faith leaders dig in on life or death decisions

Rabbi Ariel Rackovsky, leader of Congregation Shaare Tefilla in Dallas

Some clergy have opted for shorter sermons — online or in person during the coronavirus pandemic.

But the spiritual leader of this modern Orthodox synagogue — which does not livestream services on the Sabbath, when Orthodox Jews avoid using electronic devices — has continued to provide them in writing for those at home or for the few dozen people who currently can worship with him in person.

“We try and limit the duration of our services and I realize something that my members have been trying to tell me for quite some time, which is that my speeches are long,” said Rackovsky, 40. “Even though there are people who may not have heard my voice speaking in quite some time, I try and make it in such a way that people can hear me delivering it.”

Rabbi Ariel Rackovsky. Courtesy of Ariel Rackovsky

He’s had to learn how to be physically distant at several funerals where he’s been the officiant and plans on the same technique at an upcoming wedding that will include about 20 members of one family.

“I’m going to leave immediately after the ceremony and not stay for the reception,” said Rackovsky. “But these are people to whom I’m very close. They’re a prominent family in our community. And under regular circumstances this would be a significant event in the Dallas Jewish calendar.”

In June, the synagogue began a phased-in reopening, with outdoor daily and then Friday services, and now indoor services with a maximum seating for 26 men and 22 women with physical distancing.

He acknowledges “relentless waves of disappointment” as he leads a kind of “phantom community” that he knows exists with real people he cares about but cannot currently care for in many of the ways he did months ago.

“There are times when I, in fact, do feel optimistic but it’s so hard,” he said. “It’s just really, really difficult to feel that when there’s so much uncertainty and to try to be strong even when you’re not necessarily feeling inspired or you’re not necessarily feeling optimistic.”

Rackovsky said focusing on self-care has also been challenging. His wife is a physician, so if they were to take a road-trip vacation, that could have a number of consequences, including the need for him to abide by his synagogue’s new requirements that people stay away for two weeks if they have traveled.

He has instead attempted smaller ways of taking time for himself during the pandemic.

“At the beginning, I took long walks and now it’s generally, on average, 100 degrees here,” he said. Now, he sometimes avails himself, in a physically distant way, of a cooler option.

“I try and swim on occasion; I guess that is sort of a mini-respite,” Rackovsky said. “People are gracious enough to let their rabbi swim in their backyard from time to time.”

The Rev. Aqueelah Ligonde, interim pastor, First Presbyterian Church of Far Rockaway, New York

This transitional leader of a Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) congregation was working to help clarify its future plans through a “vital congregations” initiative. Then the pandemic caused a “big jolting” in its members’ regular meetings with other New York churches.

Now, she has instead been aiding the predominantly Black and Caribbean-born congregants in figuring out their present context. She leads dozens either in an 8 a.m. phone call — for older members not on Facebook — or 5 p.m. “dinner church,” where she preaches from her dining table via her church’s new YouTube channel.

“I don’t have dinner,” said Ligonde, 43, “but I simply try to create this kind of space where we’re all at the table together.”

The Rev. Aqueelah Ligonde offers a prayer through a megaphone during a protest. Courtesy of Aqueelah Ligonde

She had been prerecording the entire Sunday worship services initially but that changed after the death of George Floyd, a Black man killed in Minneapolis police custody in late May.

“I decided to go live with the sermon ’cause I felt like I needed to be in front of them,” she said of the practice she has continued since. “I needed that kind of connection.”

Ligonde has used her creative skills with iMovie for other parts of the service, sometimes spending hours for special days, such as the Sunday when they celebrated graduations.

“I tried my best to make our little Zoom worship as special as humanly possible,” she said, describing how she pieced together submitted videos of 10 little girls dancing as they would have in person for the service that also marked the end of the Sunday school year.

“I was like, well we can still do it — it’ll be more work on my part, but wouldn’t it make them so happy?”

After growing exhausted over the first couple of months of the pandemic, she realized she needed to take care of herself.

She started centering prayer, in hopes of calming herself as she prepared for sleep; had Zoom dinners with her husband and friends; and bought her first bike, on which she cycles around Long Island.

Ligonde is looking forward to the last Sunday in July, when she won’t be preaching, and the last one in August, when she plans to take a week off. The Holmes Camp and Retreat Center in upstate New York is offering Presbyterian pastors “some Sabbath time” with a virtual service their congregations can join.

“I won’t do worship but our congregation will worship with a thousand other people participating in what the camp has put together,” she said. “And so I don’t have to write a sermon. I don’t have to edit a video. I don’t know what I’m going to do on Sunday — roll around, I don’t know, spin around in circles, I don’t know — but it won’t be in front of Zoom.”