(RNS) — At 4 a.m. in Houston, Afshan Malik wakes up to pray tahajjud, the voluntary night prayers for Muslims. That earns her 5 points. She wins another 20 points for salat al-tasbih and salat al-haja, the prayers of forgiveness and need. Five more for qada yawm, to make up for obligatory prayers missed over the years; another 5 for staying awake until sunrise; 1 for performing the mandatory fajr prayer; and an extra point for doing so just as dawn breaks.

By the time her five children wake up, Malik has already scored nearly half the 100 daily points she can earn as a participant in this year’s Pilgrims at Home competition.

The Pilgrims at Home game, launched in 2011 by Sheikha Tamara Gray and managed through her women’s Islamic education nonprofit Rabata, has been running for 10 years. Organizers describe it as an Olympics for ibadah, or worship.

Around the world, 1,680 Muslim women are participating in this year’s game, hoping to “find hajj at home.”

The intensive worship regimen is designed by female scholars as a way for all Muslim women to engage spiritually with the sacred first 10 days of the Islamic calendar month of Dhul Hijjah — parallel to what millions of Muslims do in Mecca on the same days during hajj, the holy pilgrimage considered obligatory for all physically and financially able Muslims to perform during their lifetime.

RELATED: Imam Omar Suleiman: As an isolated hajj begins, Abraham’s trust in God is ours

At the start of Dhul Hijjah, hundreds of Muslim women from around the world team up and compete to stretch their worship to the limits. This year, more than 300 teams of five are playing.

“As a player you feel this hope that you can definitely reach greater spiritual heights, that you can flex those spiritual muscles more than before,” said Malik, who serves as Rabata’s director of development.

Afshan Malik. Courtesy photo

Malik has competed every year since it began in 2011 — with the exception of 2018, when she went to Mecca to perform hajj. This year, her team of five women across North America calls itself the Nafs Ninjas.

“It’s just 10 days of intense worship but I feel like that carries over to the rest of the year, too,” Malik said. “For the rest of the year, you tell yourself, ‘OK, I’m going to try to get up for tahajjud,’ and you have this attitude, like, ‘I already know I can do this, because I’ve done it in this game.’”

This year, the game is taking on a new meaning as the pandemic has closed the hajj to international pilgrims. Saudi Arabia has limited the pilgrimage to just 1,000 locals.

“Because of corona, it just seems like doors are being shut, one by one. With this door now shut for us to travel and actually make hajj, people are looking for a place to let out this emotion and energy,” said Fadiyah Mian, who heads Rabata’s Circles of Lights spirituality programming and leads the games.

“What better way than to come together with sisters around the globe and compete in ibadah and engage in deep worship?”

Players calculate their team scores in shared spreadsheets, cheer one another on in WhatsApp chat groups and meet nightly over video calls for Quran readings and talks by female scholars.

The first 10 days of Dhul Hijjah are described within Islamic tradition as the best days of the year, bringing special blessings for those who devote themselves in worship. But the period’s holy status goes largely unacknowledged today, organizers said.

“It’s very heartening to see that people are forming a connection back to the purpose of this pillar of our faith,” Mian said. “We’ve kind of disconnected ourselves unless you’re actually there, in Mecca. But it actually, within our deen (faith), has meaning and purpose.”

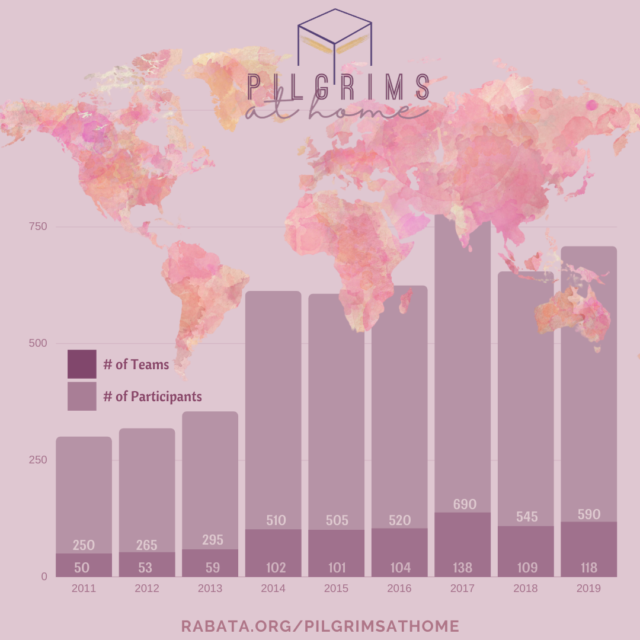

The number of players and teams in the Pilgrims at Home game since 2011. Image courtesy Rabata

The pandemic has contributed to a spike in players, with last year’s cohort of 590 players nearly tripling this year.

“I feel like 10 years ago we had no idea there would be covid, we had no idea there would be this situation where nobody could go for hajj except for the Saudis. And the importance of this game has suddenly become really serious,” Gray told players in a video kicking off this year’s Pilgrims at Home program.

A prominent Islamic scholar and educator, Gray founded Rabata to bring traditional Islamic learning to Muslim women. The organization serves up affordable Islamic courses through an online academic program. It also publishes books through its publishing arm Daybreak Press and has a brick-and-mortar bookstore in Minneapolis.

“I never would have imagined back then that this game would have taken off like this, that we would still be playing it with more and more and more players playing it,” she said.

Sheikha Tamara Gray. Photo courtesy of Rabata

This year also saw more newcomers who were unaffiliated with the organization before, likely due to the pandemic-related increase in Rabata’s online programming. With mosques closed around the world and digital communities thriving instead, the organization launched a virtual mosque, dubbed Masjid Rabata, for women and families.

“We already knew the space was going to be different, just with the fact that there’s so many people who were planning on going to hajj but their plans ended up changing,” Mian said. “But people are also just looking right now. They’re really striving, searching, reflecting and turning inside. There are a lot of players right now who didn’t even say their fard (obligatory prayers) before starting this.”

Each competitor can score up to 1,300 points for her team through acts such as fasting, completing a full recitation of the Quran, performing extra night prayers, or reading the Quran’s longest chapter in a single day.

RELATED: A down payment on making hajj easier for Muslim women

For Hikmah AbdulGafar, who is playing for the first time with a team from Nigeria, that provides a helpful structure to her lockdown-inspired efforts to “salvage” her spirituality.

“I fell in love with the thoughtfulness and how concrete the game plan is, more concrete than my original plan and also with more ibadah,” she said. “After Ramadan, I promised myself to do more towards my spirituality by maximizing the best days of the year.”

Each act is weighted based on how heavily it is emphasized in Islamic tradition, Gray explained. Most acts that earn points are extra rituals of devotion; missing one of the mandatory five daily prayers loses a player points.

Fadiyah Mian. Courtesy photo

“All of this is meant to teach us about how our book is going to look in front of Allah,” Gray said, referencing the Islamic tradition in which two angels record all of an individual’s good and bad deeds. The result of the 10-day competition, she said, is a “paradigm shift” in the way participants conceive of worship.

After the program, players return to their normal lives, ideally integrating increased devotional practices into their routine.

But participants say the worship schedule is so rigorous, and players so tightly bonded by the experience of encouraging team members, that it feels like participants have returned from a physical journey to a holy place.

“You actually feel like you’re a part of it, like you’re there,” said Mian, who has participated in every game since 2011 except for the two years she performed hajj in Mecca.

“It’s something very celestial,” she said. “Then when Eid hits, it feels like you’ve actually made hajj, like all your sins are all forgiven and you’ve been spiritually cleansed.”