(RNS) — Young Muslims’ efforts to keep their communities connected during the holy month have birthed virtual iftars, Quran study groups, game nights and trivia nights on nearly every possible platform: Zoom, Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, the Discord gaming chat app and even the video game Animal Crossing.

While originally meant as stopgap measures to replace the community fostered during in-person Ramadan get-togethers, organizers of many of these digital efforts say, participants quickly realized they had tapped into something special — not just a replacement for mosques — by going online.

“I think that’s 100% our biggest takeaway,” said Uneeba Mubashsher, a Toronto-based user experience researcher who co-founded Remote Ramadan 2020. “Going into this, everyone thought that Ramadan in community would be completely lost, but we can actually build meaningful relationships with technology.”

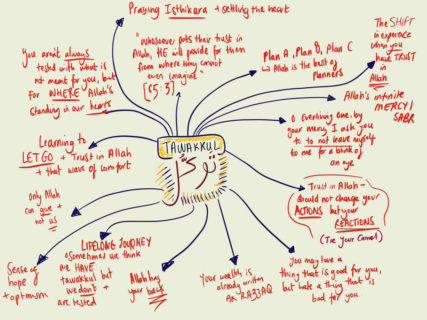

Notes from a Chit Chat Chai virtual meeting during Ramadan 2020 about the Islamic concept of tawakkul, an Arabic word meaning “trusting in God’s plan.” Image courtesy of Chit Chat Chai

Re-creating the experiences of communal iftars and reflection circles virtually ended up adding something new — something many say they don’t want to forfeit when their mosques reopen.

Take Chit Chat Chai.

The group was founded last year by junior doctor Inayah Zaheen as a “social-spiritual” discussion circle for women at her suburban London mosque. This Ramadan, the group was forced to go digital. Members use a WhatsApp group to keep connected and coordinate their weekly Zoom get-togethers.

“While we missed having that palpable sense of chatter in the air while hosting in-person sessions, there was a beauty in the shared sisterhood we were able to foster digitally,” Zaheen told Religion News Service. “Alhamdulillah (praise God), going digital in the context of lockdown was a huge blessing, whereby we were able to extend our reach.”

The move online transformed their local group into an international gathering, with women joining from as far as South Africa, Indonesia, Malaysia and the U.S. They held far more sessions than would be feasible physically and added additional sessions for teens and children, who could do arts and crafts from home under parental supervision.

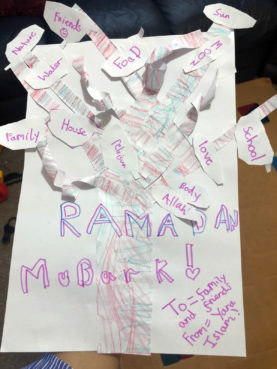

Children created artwork during online Chit Chat Chai sessions this Ramadan. Image courtesy of Chit Chat Chai

When the outbreak subsides, Zaheen plans to once again focus on in-person meetings for women at the London mosque. But she will also hold online sessions alongside in-person ones whenever possible, and create a blueprint for women around the world to create satellite Chit Chat Chai circles in their own neighborhoods.

“The overwhelming feeling has been one of sustained spiritual growth and nurturing, through new friendships and connections, with the common thread of gathering virtually for the sake of Allah,” Zaheen said. “And it is a Ramadan we will fondly remember forever, inshaAllah (God willing).”

Before the outbreak, Mubashsher and her friend Ibrahim Ayub, a strategy and design consultant in New York, were organizing an in-person event for Muslims. Two weeks before Ramadan, as the reality sunk in that Muslims would be celebrating the holy month under lockdown, the pair pivoted toward building a project to fill their community’s needs.

Muslims were most concerned about maintaining their spirituality, mental health, community and charity, the co-founders discovered through interviews and surveys of over 80 people.

“We wanted to hit on all four of those areas,” Ayub said. “So that was our mission, to keep people spiritually and socially connected while physically distant.”

The result was Remote Ramadan 2020, a community initiative centered on a private Facebook group with over 800 members — and so many posts that Ayub quickly turned off his notifications — as well as a weekly newsletter with about 300 subscribers. Each issue was filled with members’ reflections on the month and curated fundraisers and online Islamic programming.

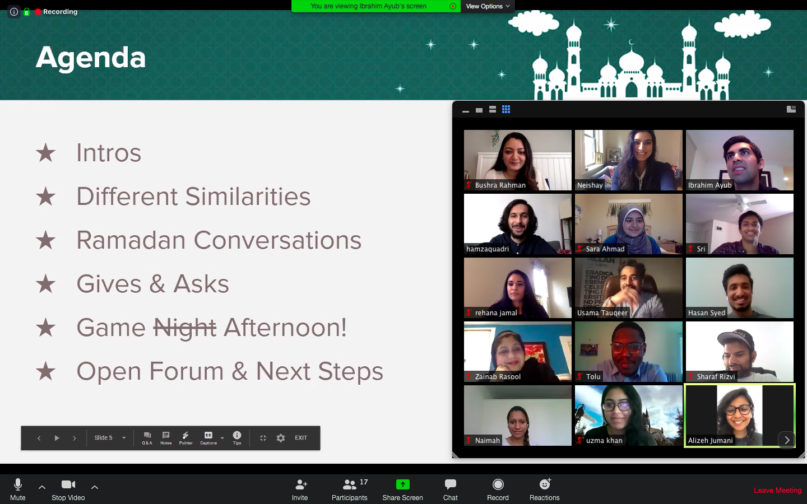

And every Saturday, they held a two-hour “bazaar,” a Zoom video call where over a dozen participants gathered to reflect on life in quarantine, share lessons from Ramadan, discuss their wellbeing, get to know one another and play games.

“This was really a lesson for me in how quickly we can form community,” Ayub said. “If you create a space and foster inclusion and open-mindedness, people really quickly build a bond. We all formed an attachment and had a magical time together.”

People participate in a weekly Ramadan bazaar virtual meeting hosted on Zoom by Remote Ramadan 2020. Screengrab courtesy of Ibrahim Ayub

Having just two weeks to pull the project together meant they couldn’t do everything they wanted, including charity challenges, workshops, breakout gatherings for members with different interests and in different time zones, or themed events such as henna nights.

“Next time, inshaAllah,” Mubashsher said.

Ramadan has ended, but quarantine has ensured the need for community has not.

And even once lockdown measures lift, many Muslims do not have access to an active Muslim community in person due to distance, disabilities or language barriers.

One participant in Minneapolis programmer Fadumo Osman’s Remote Iftar group had moved to Iowa for university. He knew no other Muslims in his area – his family is in Europe – and told participants on the call that he often felt alone.

Fadumo Osman. Courtesy photo

A woman on the call who had family in the state connected them so they could meet after the pandemic subsided. Others on the call offered to host and meet him on his next trip elsewhere the country.

Osman launched Remote Iftar as a way to maintain a sense of community among Muslims, after she saw how Christian and Jewish friends tried to create a sense of normalcy as they observed Easter and Passover from home.

Over the course of Ramadan, Osman coordinated about 150 video calls with participants from about 20 countries. More than 560 people in 12 time zones signed up to take part in the virtual iftars, which featured conversations on everything from linguistics to debates over the Hulu show “Ramy.”

“It was simply the social aspect of breaking the fast that I wanted to offer,” Osman said.

During the rest of the COVID-19 quarantine, the group will shift to monthly meetups. And next Ramadan, whatever the status of the pandemic might be, Osman plans to keep the online community going.

“So far people have said that they still see themselves needing community next year, because they may move again or they’re just in a place where meeting up digitally works better for them,” she said. “Even if it’s just two people meeting up, who wouldn’t normally have met, it’s a really amazing thing to witness. The need is there, and people still want something.”

Several of the organizers emphasized that the digital gathering served as a wakeup call about how insular and unchanging their regular Ramadan routines have been in the past. And that familiarity, they said, can inhibit spiritual and social growth.

“I was in a steady state with Ramadan in the past,” Ayub said. “I knew the people I was going to see and what I was going to do. But this made me want to be more proactive and intentional about reaching out to people who I wouldn’t normally meet.”

In the past, Seattle-based photographer Zain Khazi has enjoyed sharing iftar pictures with friends during Ramadan. This year, he asked his Twitter followers to share photos of what they were eating and cooking for that day’s iftar and suhoor meals.

That quickly turned into a group chat called Iftaar Club, where young foodies found a connection that kept them going during the lockdown.

Orea ice cream samosa anyone? 🍦🥄 pic.twitter.com/3kJthRfoOO

— Hamza (@boybawarchi) May 4, 2020

Members have ended up exchanging recipes, troubleshooting pizza dough and macaron batter, sharing photos of their cooking feats and imagining creative fusion dishes, such as member Hamza Gulzar’s now-viral Oreo ice cream-stuffed samosa and Zeeshan Bakhrani’s mango lassi pie.

It’s the next best thing to cooking and sharing meals together in person, which for many Muslims are some of the most memorable moments from Ramadan, Khazi said.

“Even from the first night, it became a lot more than just photos,” he said. “People were sharing and conversing, and it really did turn into a virtual iftar. We really were eating together every night.”

Through the group chat, Khazi has gotten to know nearly 50 Muslims, across four U.S. time zones, who keep the group active at all hours. Now, they’ve created a Twitter account and are launching a Muslim foodie newsletter. In the future, he hopes to hold potluck events in person.

“Everybody across the board wants it to keep going,” he said. “It’s turned into a mini family in there. It’s become way more than just food.”