(RNS) — Japan became the only nation to have suffered an atomic bomb attack when, 75 years ago, our nation struck Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945. Three days later, a second bomb fell on Nagasaki.

In Hiroshima, more than 140,000 Japanese died when the B-29 Enola Gay dropped its single bomb. Because of Nagasaki’s hilly terrain, “only” 70,000 people were killed. The war ended days later without the need for a military invasion of the Japanese home islands.

In the early 1960s, when both sites still showed the devastating effects of the American nuclear raids, I was sent as an Air Force chaplain to Japan. My duties there included monthly visits to the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission facilities in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, where the staff, mostly American medical personnel, included enough Jewish families to constitute small viable congregations at each location.

The ABCC had been established by the U.S. Public Health Service in 1948 to study two separate control groups: individuals who survived the atomic bombs and those who were not exposed to radiation. Not surprisingly, those who lived through the attacks were struck by cancer, birth defects, heart disease, skin deformities, genetic abnormalities, psychiatric problems and other maladies far in excess of the unexposed group.

Large numbers of Japanese distrusted the ABCC because it was an American-run facility. In addition, the commission, which closed in 1975, did not provide medical treatment for the victims; its staff only studied the problems created by radiation.

In Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I conducted worship services, set up religious education for Jewish youngsters, provided kosher food and in some cases counseled both American Christians and Jews who experienced psychological problems living and working in the sites of such horrific destruction.

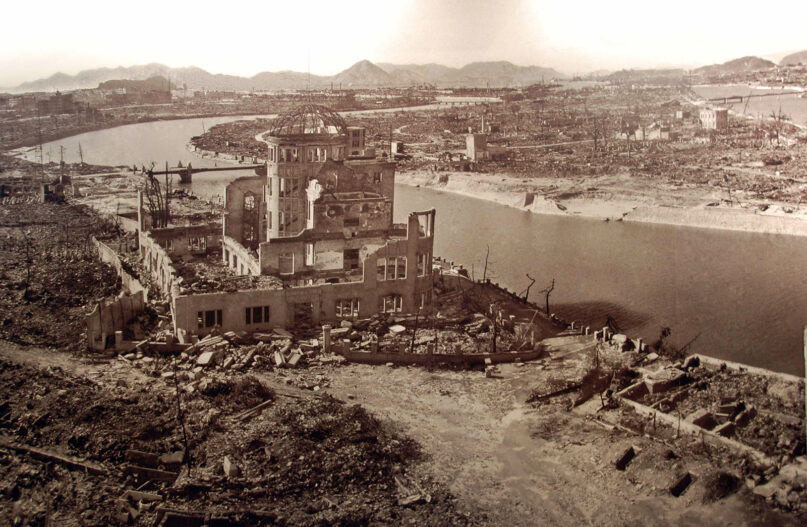

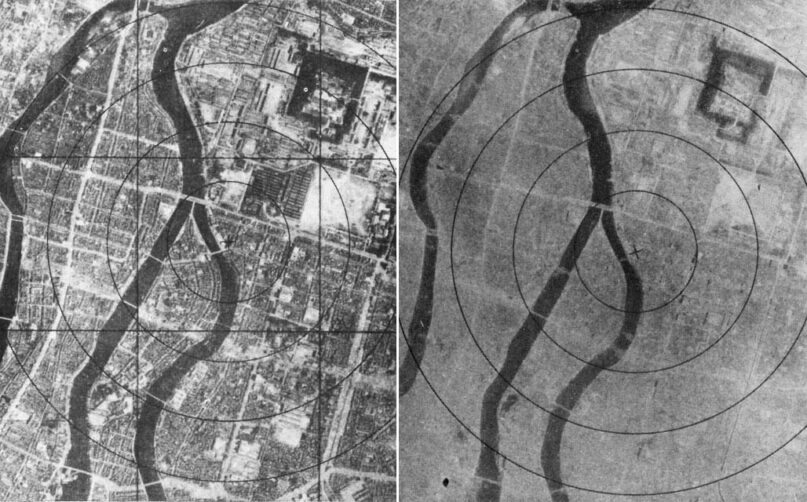

Hiroshima before, left, and after the atomic bomb was dropped on the city on Aug. 6, 1945. Photos courtesy of Creative Commons

There were clear religious parameters for military chaplains: Only a Catholic chaplain could offer last rites to fellow Catholics, and only a Jewish chaplain could recite the traditional Vidui confessional prayer with a Jew who was nearing death. But I participated in many programs, lectures, classes and counseling sessions that centered on problems that affected both Jews and Christians. I tended to alcoholics and victims of domestic violence, depression and loneliness. I discussed the difficulties of intermarriage with Japanese women and American servicemen.

While these were my primary duties, I was also involved with the overall spiritual life of the various bases and facilities I “covered” in southern Japan and Korea.

Frequently, I was the sole Westerner inside the A-bomb museums in Hiroshima and Nagasaki — the only non-Japanese person gazing at the frightening photographs of eerie shadows embedded in concrete, all that remained of people who were instantly vaporized and thrust into buildings and streets. Sometimes I was the lone Westerner visiting the iconic Genbaku Dome in Hiroshima, the only physical structure that survived the atomic attack. I was often the only American who watched Japanese children linking their paper cranes into a chain as a symbol of hope and reconstruction.

But visiting Hiroshima and Nagasaki each month for two years brought me into contact with several Japanese clergy: Christian, Shinto and Buddhist. I especially remember one Protestant minister who survived the bombing of Hiroshima, during which he lost his parents, wife and children. Stunned and dazed from the attack, he sought the comfort of some relatives who lived in the southern port city of Nagasaki. A day after arriving, the second atomic bomb destroyed much of his supposed “city of refuge.”

In one of its many efforts to build and strengthen Japanese-American friendship, the Air Force designated me to present the minister with several Louisville Slugger baseball bats for his church team. A faded black-and-white photo taken during the ceremony shows both of us smiling.

Happily, such weapons of mass destruction have not been employed since 1945, but the past record of restraint by the nations that possess nuclear weapon — a precarious balance of mutual destruction — provides no comfort for the future. Not surprisingly, Japan is among the most concerned nations about the possible sales of atomic weapons to terrorists.

President Harry S. Truman, right, reads the announcement of Japan’s surrender to assembled reporters and officials in the Oval Office, on Aug. 14, 1945. Photo by Abbie Rowe/NARA/Creative Commons

Much of the world accepted President Harry Truman’s explanation for using the bombs, based primarily on the math he offered to buttress the American position: The immediate deaths of 210,000 people, mostly civilians, was horrible in its scope, but the probable loss of more than 1 million American and Japanese lives in the planned invasion was averted.

Such an invasion of Japan would have meant deadly hand-to-hand fighting in every city, town, village, farm, street, alley, house, shop and room. U.S. forces would have confronted not only the Japanese military, but also millions of civilians, including children. I have thought a great deal about Truman’s decision, and I share his belief.

But this wasn’t the question the Japanese hurled at me during my tour of duty. Rather, they would ask: Would the United States have used the atomic bomb against Nazi Germany, a nation of white Europeans?

Chronology provides a partial, if simplistic, answer. The war in Europe ended in May 1945, two months before the first A-bomb was tested in New Mexico. But given the climate of hatred of Nazism, and remembering the devastating Anglo-American air raids, especially the firebombings of Hamburg, Berlin and Dresden, I believe the terrifying nuclear weapon would have been employed against Germany.

It’s a question I might have put to Truman himself when, a year after I returned to civilian life, I attended a public luncheon in Kansas City, Missouri, and was seated next to the former president.

After the formal niceties ended, Truman asked me many questions about Japan. In a most un-Truman-like moment, he plaintively remarked that, “Of course, Mrs. Truman and I can never visit there because of August 1945.”

(Rabbi A. James Rudin is the American Jewish Committee’s senior interreligious adviser and the author of “Pillar of Fire: A Biography of Rabbi Stephen S. Wise,” which was nominated for a 2016 Pulitzer Prize. He can be reached at jamesrudin.com. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)