(RNS) — Nearly 30 years after it was published and more than a dozen after its author’s death, Octavia Butler’s dystopian novel “Parable of the Sower” popped up on The New York Times bestseller list in early September. Like other resurrected titles, such as George Orwell’s “1984” and Albert Camus’ “The Plague,” the book seems to have gained new readers fascinated by its evocation of an American society that feels itself besieged by nature and a struggle for power.

“It feels like prophecy,” said Monica Coleman, professor of Africana Studies at the University of Delaware and a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. “It feels like she really predicted this. And I think people are reading it because she was writing about what could happen if we don’t change.”

The book, the first in a series, tells the story of Lauren Oya Olamina, a differently abled Black teenager and pastor’s daughter who establishes her own religion called Earthseed. As she travels the length of California, she gains followers.

Originally published in 1993 and re-released last year by Grand Central Publishing, the novel takes place during an election year in the early 2020s in a United States where food and water are scarce and the police serve only themselves and the wealthy. Fires ravage California, hurricanes batter the Gulf Coast and racial conflict has become more volatile. Extreme wealth disparities are exacerbated by corporations that pocket profits swollen by severely underpaying their employees. College is unaffordable for most.

There are also cannibals, slave owners and pyromaniac drug addicts setting the United States aflame one town at a time.

“Parable of the Sower” by Octavia Butler. Courtesy image

Coleman, who has been teaching “Parable of the Sower” in her courses since 2006, has been hosting an online webinar series called “Octavia Tried to Tell Us: Parable for Today’s Pandemic” with Tananarive Due, an Afrofuturist writer who teaches a course on Black horror at UCLA. The webinar, which debuted in early May, is one of several Butler-based teach-ins, podcasts and other projects that have sprung up this year.

Butler’s vision of 2020’s dystopic side makes her novel relevant, but it is her heroine, a young woman of color who deals with harsh realities with admirable strength, that inspires many readers. Asha Noor, a human rights advocate and a member of the Muslim Anti-Racism Collaborative, has been returning to “Parable of the Sower” in part because of Lauren’s example of resilience.

“It’s helpful connecting with characters like Lauren, who, despite all these horrible things, is able to envision a new future or path, and to imagine what that would look like in today’s really tumultuous terrain,” said Noor, who recently began taking a self-guided online class on the book.

Jacqueline Hidalgo, professor of Latina/o religion at Williams College in Massachusetts, said the book’s popularity could be due to those qualities Lauren has that we seem to miss in our present-day leaders: She is perceptive, decisive, practical yet imaginative and takes concrete action when faced with devastating events.

Yet Butler’s protagonist doesn’t rely on strength alone to lead. “Part of what makes Lauren such an important figure in part is her hyper-empathy,” Hidalgo said. “If we contrast that with what our leaders seem to have now, such an abrasive lack of empathy, I think that’s part of the story’s power.”

“People are hungry for the kind of alternative, hopeful, theological imagination Butler presents, as well as for an alternative form of leadership and community,” said Hidalgo.

Longtime fans and scholars hope the novel’s new readers will also resonate with Lauren’s religion, Earthseed. The premise of the faith, presented in short, lyrical verses throughout the book, is that God is change, and humans can shape God through forethought and work. Ultimately, Olamina says, Earthseed’s destiny is to take root among the stars.

The fictional faith has taken on life beyond the novel.

“I would definitely consider Earthseed one of my scriptures, scripture being that which points toward what is holy,” said Coleman, who said she has been reading more Earthseed than Bible of late.

A womanist process theologian, Coleman believes in a symbiotic relationship between God and the world. “We are in God, and God is in us; God is holy, and we are holy,” she said.

“Earthseed gives a very different view than classical theology, where you have the big God who is in charge of things,” she said. “Instead, no one is in charge. I think Earthseed really resonates because when everything is changing, it makes people feel like there is something they can do rather than just being subject to change.”

Coleman often uses the text to teach constructive theology, a postmodern approach to theology based on the idea that knowledge of God is not absolute but rises from its context — i.e., constructed.

“’Parable’ has long struck me as one of the most poignant and gripping examples of theology in context and of constructive theological method,” she said. Butler also exposes students to the idea that theology is not only the province of white European men.

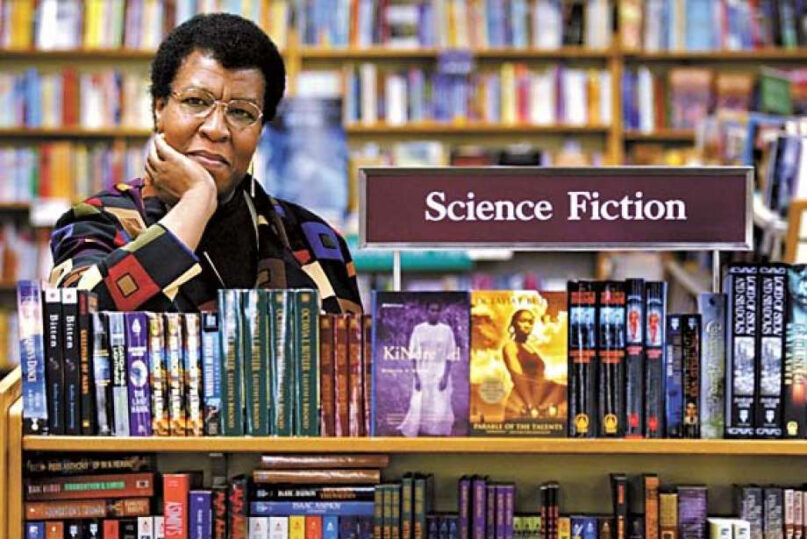

Science Fiction writer Octavia Butler poses for a photograph near some of her novels at University Book Store in Seattle, Wash., on Feb. 4, 2004. (AP Photo/ Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Joshua Trujillo)

On the whole, the book presents a rather bleak picture of organized religion. Born in 1947 in Oakland, California, and raised by her mother and grandmother after her father’s death, Butler turned away from her family’s strict Baptist faith. Olamina, too, rejects her father’s beliefs in an all-powerful God who won’t intervene on behalf of the poor in favor of a religion that teaches her how to survive.

But the book relies on religious — and often unapologetically Christian — themes; the title of the book is drawn from a story told by Jesus in the New Testament’s Gospel of Luke. It concludes with the characters planting seeds in a new community.

“I think Butler is careful not to demonize Christianity but certainly points out the trajectories it could go down,” said Roger Sneed, an associate professor of religion at Furman University. “I would read Earthseed as not a wholesale rejection of her father’s beliefs, but rather growing out of them. But for Olamina, humanity must be adaptive.”

A year before her death in 2006, Butler talked about the books’ complex treatment of religion in an interview with Democracy Now. “Religion might be an answer as well as, in some cases, the problem,” said Butler. “In ‘Parable of the Sower’ and ‘Parable of the Talents,’ it’s both.”

Though based in Christian themes, Olamina’s faith finds correspondences in other traditions. For Noor, her journey north through California reminds her of Muslims’ annual pilgrimage to Mecca as well as the journey it commemorates, that of Abraham’s slave, Hajar, also known as Hagar, after the patriarch sends her out into the desert.

In Islamic tradition, Hajar wanders with her and Abraham’s son, Ismail, searching for water until God provides it. “Hajar’s story is one of perseverance and resilience in the face of adversity,” said Noor. “Lauren is a young black woman charting a new path with complete trust in a process without knowing the end. Reading this text has deepened my own understanding of my own faith tradition and the power of one individual’s journey.”

There are echoes of Buddhism as well. Butler takes note of the impermanence of everything, a basic Buddhist principle that Earthseed captures by making God change itself. In Earthseed, one prays to oneself, a practice Sneed said is “almost Buddhist” in its suggestion that humans can address problems through right concentration and mindfulness.

Butler’s characters’ names, meanwhile, are nods to the religion of the Yoruba people of Nigeria. Lauren’s middle name, Oya, is the name of a Yoruba orisha (deity) of storms and whirlwinds who stirs change and is an advocate for women — appropriately for Olamina, who earns the name “Shaper” in the book’s sequel.

But the “Parable of the Sower” didn’t strike a chord with our current converging crises because of its insider religious references, scholars say, or even for its prophetic portrait of our times. Like Olamina’s Earthseed and any religion at its best, it lends hope in a time that has been demoralizing for many.

“Hope shouldn’t be a passive stance but definitely more active,” said the Rev. Jeania Ree Moore, a Methodist deacon and a doctoral candidate in African American and religious studies at Yale University. “And maybe Olamina’s language about shaping change and God points to the idea that we are agents in our own hope.”