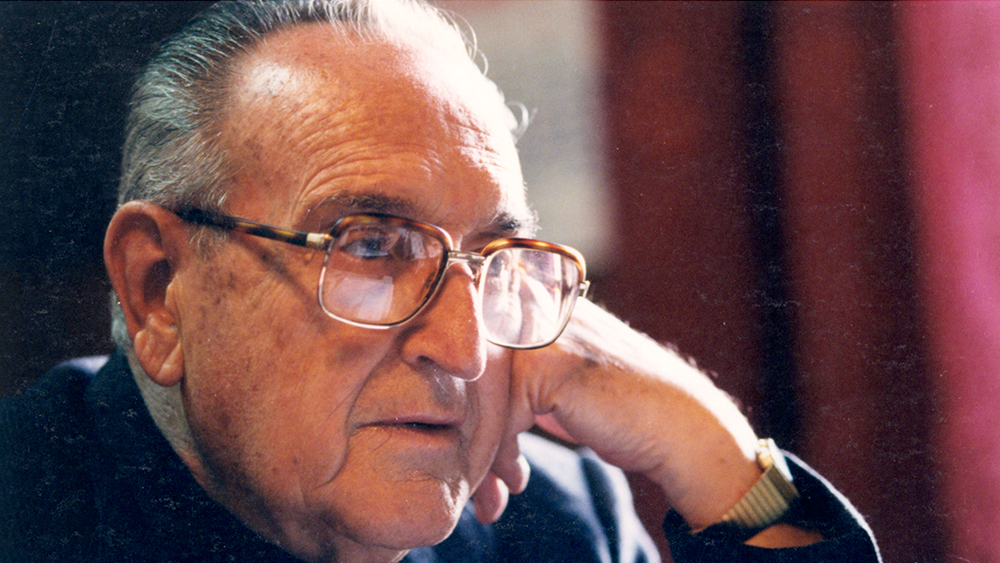

Guatemalan Catholic Bishop Juan Gerardi. Photo courtesy HBO

VATICAN CITY (RNS) — A new HBO documentary on the legacy of Guatemalan Catholic Bishop Juan Gerardi, who was murdered in the aftermath of the country’s long civil war, highlights the courageous role of Catholic clergy in the fight for democracy in Central America. It also offers a model for struggling democracies today.

“There are a lot of negative stories, films and documentaries about the Catholic Church that get made. I was attracted to the idea of this not being that,” said Director Paul Taylor in a Zoom interview with Religion News Service on Thursday (Dec. 10).

“I started to see that some of the issues at the heart of the case were still very relevant today and still very relevant outside of Guatemala,” he added.

“The Art of Political Murder,” inspired by the book of the same name, was produced by George Clooney and will debut on HBO MAX on Dec. 16.

The 1960 to 1996 civil war in Guatemala, in which the right-wing military government fought a leftist rebellion supported by indigenous communities, was among the deadliest conflicts in the Americas, with more than 200,000 civilian casualties.

Francisco Goldman, the book’s author, who was also on the Zoom call, described the junta’s suppression of the rebels as a “complete, suffocating, blanketing lawlessness.”

Gerardi began documenting the atrocities of the war as it wound down in 1995, creating the Recovery of Historical Memory Project, or REHMI. On April 26, 1998, two days after the publication of a REHMI report, Gerardi, 78, was found dead in front of the parish house of Church of San Sebastian, where he lived in Guatemala City.

Film poster for “The Art of Political Murder” Image courtesy HBO

According to Goldman, Gerardi’s murder “could have destroyed the peace completely,” but those who picked up Gerardi’s work and investigated his death after the murder “were really fighting for the country they wanted to live in,” he added, “and that fight still goes on.”

Taylor said he was struck while reading the book not only by the bishop’s courage, but the bravery and altruism of those who took up his challenge after his death. “I found that very moving, and in this very dark story I hope that people would find a lot of hope,” he said.

The documentary shows that the crime scene at the parish house “was seriously mishandled,” leading the Archdiocese of Guatemala to hire Rodrigo Salvadò, Fernando Penados and Arturo Aguilar – who was only 19 at the time – as investigators to hold the government accountable in the inquiry into Gerardi’s death. The three encouraged witnesses to come forward and ultimately challenged the power structure of Guatemala.

The REHMI report that cost Gerardi his life identified 435 massacres and listed more than 50,000 people who disappeared, finding that the government perpetrated “the vast majority of atrocities during the war.”

Most of the government’s victims were ordinary citizens and members of human rights groups. Only the Catholic Church, which had deep allegiance in local communities, could stand up to the army.

“The Catholic Church throughout the dark years of the war was probably the only thing that gave people hope,” Goldman said, adding that the church “also operated as the popular memory of the people”; its churches and personnel sprinkled throughout the country served as record keepers of the atrocities.

“The people who knew what was going on were the nuns in the parish churches and the young priests,” said Goldman, who reported on the war for many years.

Before coming to Guatemala City, Gerardi served as bishop of the impoverished Quichè region and its Mayan indigenous communities. Between 1980 and 1983, many religious and civilians were brutally murdered by government forces in the area.

People walk next to a banner depicting slain Guatemalan Bishop Juan Jose Gerardi during a rally to mark the 12th anniversary of his murder in Guatemala City, Monday, April 26, 2010. Gerardi was killed in Guatemala City in April 1998, days after presenting a lengthy report blaming the military for 80 percent of the deaths during the country’s 1960-1996 civil war.(AP Photo/Moises Castillo)

In Rome for a synod in 1980, Gerardi met with Pope John Paul II, who encouraged him to return to his mission, but he was denied entry into Guatemala on his return. Gerardi went into exile in Costa Rica and evacuated his diocese, a choice he would atone for when he was finally able to take up the seat again in 1982.

“That’s what made him so brave all those years later, the humiliation and remorse he suffered,” Goldman said. “That’s what I love about him: He has flaws; he has bad moments.”

When Gerardi came back, said Goldman, “he understood his calling and founded the diocesan office of human rights.”

After Gerardi’s murder, the government purposely confused the media narrative of his death. A priest who had lived in the parish house, the Rev. Mario Orantes, was accused of being a homosexual and involved in the murder. The case turned in 1999 with the appointment of a new prosecutor, as a United Nations commission accused the military government of genocide against the Mayans of Guatemala.

As the international pressure mounted, three members of the army, along with Orantes, were brought to trial. In 2001 Colonel Byron Disrael Lima Estrada and his son, Captain Byron Lima Oliva, and José Obdulio Villanueva were all sentenced to 30 years in prison for Gerardi’s murder. Orantes was charged with 20 years for his role as an accomplice.

The trial was a major test of Guatemala’s nascent democracy. The sentence recognized Gerardi’s murder as a state crime, the first public acknowledgment of the widespread corruption by the military government.

Besides the young ODHA investigators and the human rights activists, such as Ronalth Ochaeta, there are other heroes in Gerardi’s case. The trial judge, Yassmin Barrios, pursued justice despite an attack in which grenades were tossed into her home.

Ruben Chanax, a homeless man, was initially made an accomplice to the murder and a spy before sacrificing himself for the sake of justice.

It is precisely this theme of redemption that makes “The Art of Political Murder” a captivating watch. Flawed individuals faced with unsurmountable odds prove their courage and determination time and time again, inspired by Gerardi’s example.

“Gerardi’s spirit lives,” the documentary concludes, and Taylor and Goldman believe that this spirit is needed more than ever, as nationalism rises worldwide and, with it, threats to judicial institutions globally. “The fight for justice continues,” they added.

The article was updated to correct the name of the Direcvtor of ODHA, Ronalth Ochaeta