(RNS) — When he was 8 years old, Gary Laderman’s grandfather died of a heart attack while taking a bath in his family’s home.

The rabbi who rushed to the scene to console the family offered the grief-stricken young Laderman a bit of advice: “Don’t think about death.”

Laderman didn’t take it.

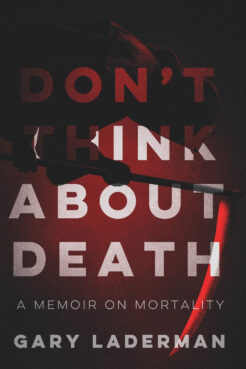

In fact, he made death his life’s work. The professor of American religious history and culture at Emory University has now written his fourth book on the subject, cheekily titled, “Don’t Think About Death: A Memoir on Mortality.”

The slim volume explains how he, and Americans generally, obsess over mortality. Death propels medical advancements. It’s a staple of popular culture and art. It’s part of our political discourse.

Laderman has become the foremost “death expert” in American life. His first book explored American attitudes toward death from the Revolutionary era up until Abraham Lincoln’s funeral journey. His next book was on the cultural history of the funeral home in the 21st century; his third was about death and celebrity worship.

As Christmas approaches in the midst of the worst pandemic in a century, RNS talked to Laderman about his new book, celebrity deaths, changes in the way we dispose of bodies and how the absence of loved ones due to COVID will be felt so acutely by many Americans.

Professor and author Gary Laderman. Courtesy photo

“This holiday season is going to be a killer, existentially, spiritually, emotionally, mentally because of the additional weight of not being able to visit family or having this powerful fear of the virus that’s difficult to pinpoint,” Laderman told RNS. “We’re living in a time that will have a profound impact on so many aspects of our lives.”

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

You write about how your interest in death preceded your interest in religious studies. Why was religious studies a good vehicle for your inquiry into death?

For me, it was a perfect fit. Intellectually as I started to pursue the topic, it’s where all the action was. Death is the central human experience that helps to establish the religious imagination. The connections between death and religious thought and practice are very closely tied together.

You write that you were in a record store when you heard the news of John Lennon’s death. Dec. 8 was the 40th anniversary of his death. Why are we so moved by celebrity deaths?

It’s a strange social phenomenon to think about the kind of attention and energy given to celebrities and what people get out of these connections with people they don’t know but spend their lives trying to get to know and feel a certain kind of intimacy with. It can be as traumatic as losing a family member for many of those fans, because of that sense of intimacy and connection to ultimate values and concerns that people bring to their relationship to John Lennon or Elvis Presley or whatever celebrity you put in there.

A woman places a drawing on the Imagine mosaic at Strawberry Fields in New York’s Central Park to remember John Lennon, Tuesday, Dec. 8, 2020. The rock star and former Beatle was shot to death 40 years ago outside his New York City apartment building by a fan on Dec. 8, 1980. (AP Photo/Mark Lennihan)

So we’re more attuned to celebrity deaths than religious texts that teach us about death?

What I try to suggest is that popular culture is a critical and important resource for how people make sense of their lives and the values they live by. Celebrity is one manifestation of that. It’s where we invest in thinking, ‘What are my values?’ ‘How do I understand myself?’ ‘Whose ideals can I aspire to live by?’ It comes more from celebrities and entertainment than from the traditional sources that used to provide answers to those questions, like the Bible, the church, the temple. Those are obviously still in the mix, but over the last couple of centuries they’ve had to compete with other sources.

How is COVID-19 different from other tragedies involving mass deaths?

I’ve been thinking about that a lot. It’s not an uncommon experience in human history where great numbers of people die. Those become usually landmarks or cornerstones for social identity — finding a way to memorialize large numbers of people dying. It seems that’s easier when it’s some kind of warfare or act of terrorism. There’s an enemy or an assault on the body politic. The memorialization is much more automatic and scripted. We’re more prepared for that.

When you’re talking about a pandemic or public health crisis, I don’t think we have the tools to collectively memorialize the people who are dying. The virus is not concrete enough to be an enemy that can bring the nation together. Instead, we’ve seen how it’s become politically divisive and polarizing.

We’ve seen a movement of dying at home and sitting with the body after the death, maybe even washing the body. You write that as a society we’ve grown more comfortable with corpses. Do you see that outlasting COVID-19?

“Don’t Think About Death: A Memoir on Mortality” by Gary Laderman. Courtesy image

I’m not sure. An interesting comparison is AIDS and the uncertainty around that disease. The early response among people in the funeral industry was around fear of contagion. In some cases, funeral homes turned away families, which is sort of unheard of in the funeral business. AIDS changed how we think of death and how we commemorate certain communities. We’re in a new situation now. One important element of the history of American funerals and the treatment of the dead has to do with intimacy. When someone dies, there’s someone close to the body — a nurse, a doctor, a funeral director — who can access it and bring the living into closer contact with it. Now there’s a forced change that’s dramatic and jarring. We have to live with a virtual intimacy. We can only get close to the body through image or video connection. How does that change our connection to the dead? There are political and religious implications: for example, mobile morgues being established in El Paso, Texas, recently. No intimacy. No control over the fate of the body for those family and friends personally impacted by death. But in addition to the personal tragedies of each body in those mobile morgues is the collective impact they will have, haunting the national psyche for years to come.

Are more people bypassing funeral homes?

Before the 1960s, the dominant form for most Americans was an embalmed body, an open casket, a funeral home. After the 1960s, you see the disposal of the dead begins to be loosened and disconnected from those traditions. There’s more of a DIY aspect in which the consumer can shape the details of how they want to care for the body of their loved one. Having said that, the funeral industry is nothing if not adaptable. They change with consumer desires. They’ve opened up and helped people with alternative paths. There’s a wider spectrum of choices, but they’re still involved in helping people.

Christmas is a time of celebration. But a lot of people are also grieving loved ones who are no longer there to celebrate. It’s not a happy holiday for all, especially this year. Why is death so much a part of Christmas?

Whether we’re talking about Christmas or Hanukkah or Kwanza, the New Year, these holidays are religious. They’re religious in ways that aren’t tied to whether you’re Christian or Jewish or whatever. They have a certain sacred power in how we measure and mark the passage of time. It has all kinds of connections to gift-giving and being with family and friends and feeling the love. The holidays at this time of year provide ritual forms of continuity and reassurance that are in place in part to help us cope with the underlying realities of loss and mourning that is so much a part of what it means to be alive.