(RNS) — “The U.S. Capitol is not impregnable,” Glenn Martin cautioned his students at Indiana Wesleyan University. “Never forget this, my friends! Never forget this!” he shouted, rising up on his toes to elevate himself to a stately shortness. “If the British could access and burn it in 1814, it could fall again. And don’t think only of foreign foes. A political party or leader might very well raze it rather than forfeit power!”

I’ve thought of that lecture often since I heard it in 1975. Recently, I’ve thought about it more.

In his book “Prevailing Worldviews of Western Society Since 1500,” published after he died in 2004, Martin reminded us that American Christians should “reverence government as a gift of God for the orderly procedure of man in a fallen world.”

The reason is that “to deny government leads first to anarchy, but ultimately back to tyranny. Out of anarchy must necessarily come authoritarianism, because anarchy produces nothing but a vacuum, and a vacuum must and will be filled.”

Martin believed that there are three serious threats to our “God-ordained” country. The first threat is the easing in of socialism and communism. He feared that the passionate students he had seen come through his classroom were susceptible to Karl Marx and his hollow promises of progress — from socialism to international socialism, and ultimately to a classless society.

They could do so only by ignoring history. Billions of people have suffered in abject poverty and pogroms in socialistic schemes elsewhere. Millions, including former first lady Melania Trump and newly elected U.S. Rep. Victoria Spartz of Indiana, have fled them.

Marx hardly guarantees an end to political violence. “To move dialectically,” he wrote, involves “force, violence, and bloodshed.”

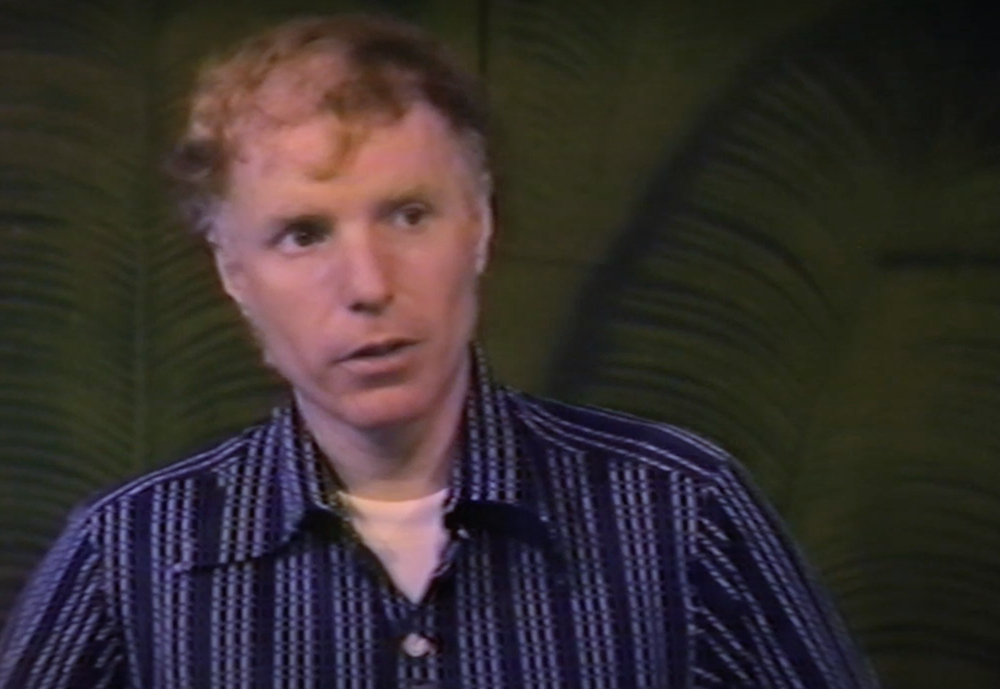

Glenn Martin lectures in 1977. Video screengrab

Martin’s second perceived threat is that a liberal view would exalt the state. The pandemic has accentuated this fear, as numerous governors have instituted draconian measures in the name of stopping the virus’s spread. So has the crackdown on free speech in the form of Twitter and Facebook bans. In a new book I co-edited with Christopher J. Devers and Todd C. Ream, “Public Intellectuals and the Common Good: Christian Thinking for Human Flourishing,” Miroslav Volf reminds us that Socrates “was condemned to death because his attachment to truth brought him into competition with the state and its gods.”

The sudden popularity of George Orwell’s “1984” is one indicator that some are worried. Others have already been sounding the alarm on America’s bent to totalitarianism: Hillsdale College President Larry Arnn, who cut his scholarly teeth researching for Winston Churchill’s official biographer, Martin Gilbert, noted in a speech last year the likeness of the American political landscape to totalitarian novels by Orwell, Aldous Huxley, Arthur Koestler and C.S. Lewis. “We can see it (totalitarianism) in the rise and imposition of doublethink, and we can see it in the increasing attempt to rewrite our history,” Arnn said.

Martin’s third threat might surprise anyone who’s been following along: He feared the shift “if only inadvertently” from the biblical Christian worldview of Augustine to evangelical Christianity. “That is, we no longer recognize God as applicable to all of life, having accepted the dichotomistic (and dualistic) mindset of sacred and secular.”

Following Augustine, Martin would have loathed the vitriolic exchanges during the two impeachments of President Donald Trump as much as he would the president’s words from the stage at the Ellipse. “A man may count himself happy in having license to slander; but he will be far happier if deprived entirely of that liberty,” Augustine wrote in “City of God,” before continuing:

Then he can drop the silly pose of superiority and take the opportunity to raise what objection he likes, as one really interested in getting to know; he can ask his questions in a spirit of friendly discussion, and listen when those whom he consults do their best to give a courteous, serious, and frank reply.

Martin notes that the fulcrum of all such meaningful discussion is the law of noncontradiction. Two opposing facts cannot both be true at the same time and in the same respect. The attack on city, state and federal property and the killing of innocent people in the process — including civil servant defenders such as Capitol police officer Brian Sicknick — is always criminal. Somehow, many Americans have digressed into calling the same criminal actions by different names.

Protesters storm the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, in Washington. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

The slaying of a police officer by any other name is still murder. The killing of a Trump supporter is still murder. The shooting of a jogger by any other name is still murder.

Four years ago, on the day after Inauguration Day, Madonna solemnly stared into the cameras and said with calculation, “I have thought an awful lot about blowing up the White House.” Inciting rhetoric? Other similar statements have by now been trotted out so many times they have become trite — but trite isn’t synonymous with trivial.

Martin calls biblical Christians to look first to Jesus to repair our society. Heather Templeton Dill, in another essay in the book cited above, reminds us of the value of doing so in an age of pluralism. In a pluralistic society, the role of faith and commitment is elevated, and church becomes a “voluntary association,” she writes, citing the work of Peter Berger. That pluralism helps people of faith shore up their nonnegotiables.

In 2004, I had the privilege of giving Martin’s eulogy before a packed crowd. The diversity of faces and their stories reminded me that his maxims are based on biblical principles, not personalities. He often called the Bible “God’s word in verbal propositional form,” for all people regardless of their heritage or position. “God is no respecter of persons.”

A few days earlier I had sat at his hospital bedside, where brain cancer had pulled him into a coma. The irony of a brilliant mind being shackled such was not lost.

The next day a remarkable story began circulating. The night nurse began hearing sounds around 3 a.m. Martin was lecturing, one arm up, as if writing on the chalkboard. He was giving a last lecture, animated, and what we surmise was his standard outline of Augustine’s biblical Christian worldview. Then, as if reaching its conclusion, he put down his arm and once again went silent. His last lecture — not to a political party, but to God, perhaps, sovereign and over all of life.

A biblical Christian is evangelical, but not all evangelicals are biblical Christians. All should reverence government as a gift of God for our orderly procedure in a fallen world — especially in the face of horned shamans threatening our elected representatives and antifa militants welcoming President Joe Biden by burning flags and vandalizing buildings, including the Oregon Democratic Party headquarters.

(Jerry Pattengale is the author, most recently, of “Public Intellectuals and the Common Good” and “Inexplicable: The Spread of Christianity to the Ends of the Earth,” the latter now a TV series on TBN, and the forthcoming “The New Book of Christian Martyrs.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)