(RNS) — Phil Vischer was driving home from his studio and listening to NPR when he had another of his big ideas.

Vischer, the creator of “VeggieTales,” the animated series in which produce-aisle items act out Bible stories, says he often talks back to NPR’s stories — with his characteristic wisecracks, of course, but also with probing questions when he feels the reporter missed something.

“I was having some really interesting conversations with myself in my car,” said Vischer, the voice of “VeggieTales” host Bob the Tomato. “And then one day, I wondered if anyone else would like to listen in to these conversations?”

The answer, it turns out, is yes.

Since 2012, Vischer has recorded more than 440 episodes of the “Holy Post,” a weekly podcast that he co-hosts with his friend, Christian author and speaker Skye Jethani. The show has also spawned videos about race, politics and the history of the evangelical movement, drawing millions of views.

While the early audience for “Holy Post” was largely made up of “VeggieTales” fans, in recent years the podcast has increasingly spoken to millennial evangelicals who have been turned off by developments in the movement — “VeggieTales kids,” Vischer calls them, whose spiritual development he still sees as his responsibility.

“They’re growing up and looking around at white evangelical Christianity in America, saying, ‘Gee, I liked it when Bob taught it, but I don’t think I like it anymore,'” he said. “I felt a bit of a responsibility to keep teaching the faith.”

RELATED: Phil Vischer still has hope for the future of VeggieTales, 25 years later

The podcast and the videos are part of Vischer’s latest attempt to reinvent himself in the years following the collapse of the company behind “VeggieTales.” It’s still a work in progress, he told Religion News Service.

“Holy Post” podcast logo. Courtesy image

The inspiration for the “Holy Post” actually predates Vischer’s becoming a household name in evangelical Christian culture during the 1990s. The Bible school dropout — he flunked chapel — first pitched a David Letterman style talk show for teens but no one bit. So he moved to another idea — making an animated show about talking vegetables that love Jesus.

That idea hit at just the right time.

In 1993, when “Where Is God When I’m S-Scared?” — the first “VeggieTales” episode — debuted on VHS, Christian retail and videocassette sales were both booming. The annual Christian Booksellers Association meeting drew more than 12,000 people that year, including representatives from more than 2,600 stores, according to a history of the CBA.

Vischer’s Big Idea Productions eventually grew to 200 employees and $40 million in annual sales. But the company grew too big too fast, causing cash flow problems. The company’s first Hollywood film, “Jonah: A VeggieTales Movie” did well at the box office but wasn’t a major hit. Then the company lost an $11 million lawsuit filed by distributor Lyrick Studio for breaking an agreement.

After declaring bankruptcy, Vischer lost just about everything, including rights to Bob, his sidekick Larry the Cucumber and all the other “VeggieTales” characters, as well as all the songs he’d written.

“Everything fell apart because the dream I was pursuing wasn’t from God,” he told RNS. “It was about me and my insecurities.”

Even at the height of the “VeggieTales” success, he was skeptical of Christian consumer culture.

“I’ve always been looking around, saying, are we doing this right?” he said. “Is this what we are supposed to be like?”

“VeggieTales” characters in a Christmas episode. Image courtesy of VeggieTales

Looking back, he has some ideas on why “VeggieTales” was so popular — which he first shared during a visit to Yale Divinity School at the invitation of theologian Miroslav Volf. The show was able to be both funny and sincere at the same time. It fit a need for parents who had grown up on David Letterman and “Beavis and Butt-Head,” where everything was a joke.

At “VeggieTales,” Vischer said, “it seemed like we were going to joke about everything.”

“Then we’d turn on a dime and tell kids that God made them special and he loved them very much,” he said. “I’ve said it was like David Letterman and Billy Graham had a love child and that was Bob the Tomato.”

Robert Vischer, Phil’s brother and dean of the University of St. Thomas law school in Minneapolis, said he’s proud of his older brother’s accomplishments. Phil, he said, is doing what he always has done: tell stories and try to make the world a better place.

“I think to be an effective storyteller, you have to have empathy,” said Robert. “You have to be able to help your audience get outside their own heads and inhabit the experience in perspective of someone else. I mean, that’s what great storytellers do. I think the way he has grown is consistent with how we all hope to grow, which is gradually widening his circle of empathy.”

Regrets from the Big Idea years, Phil Vischer said, include the fact that good people followed him as he chased his dreams and were hurt when things fell apart. “I wish there had been another way,” he said.

Like “VeggieTales” — and like the sunnily morose Vischer — the podcast mixes serious topics and humor.

A late December episode featured a wisecracking segment about honeybees using chicken manure to ward off murder hornets, followed by a discussion of the “Jericho March” in Washington, which protested the results of the 2020 presidential election.

Lauren Mulford. Courtesy photo

At one point Vischer poked fun at the presence of Christian author and radio show host Eric Metaxas and MyPillow pitchman Mike Lindell at the event.

“Never has so much potentially toxic masculinity been mixed with the hugging on pillows,” Vischer told listeners.

Among his listeners is Lauren Mulford of Sanger, Texas, who said she started listening to the “Holy Post” last fall, just before the election, after a friend recommended it.

“It was such a nice reprieve from the hysteria was going on in a lot of evangelical circles,” said Mulford, who was waiting out the winter storm last week in Texas with her husband and their six kids.

She watched “VeggieTales” a few times while growing up but really got into the show in college, where friends were big fans. Her kids now watch “VeggieTales” and she still enjoys watching it with them.

RELATED: VeggieTales creator releases viral video on race

Casey Erickson and her family, who live outside of Dallas, are longtime fans of “VeggieTales” as well as “What’s in the Bible,” Vischer’s video series that walks kids through the books of the Bible. She often listens to the “Holy Post” while she is shuttling her kids around.

She said the podcast has introduced her to a number of books on race and Christian nationalism that she hadn’t been aware of, such as Jemar Tisby’s “The Color of Compromise,” Esau McCaulley’s “Reading While Black” and Kristin Du Mez’s “Jesus and John Wayne.”

Casey Erickson. Courtesy photo

Michael Agapito, a seminary student who works at a Baptist housing ministry in Champaign, Illinois, has fond memories of watching “VeggieTales” with his parents, who are immigrants from the Philippines. The show, he said, encouraged kids “to think biblically about morals.”

“It taught you things like how to forgive other people and love your neighbors, which are still important today,” said Agapito.

Growing up in the evangelical church, Agapito also heard a lot of culture war rhetoric, which clashed with some of the messages “VeggieTales” taught him. He believes many of his peers have become disillusioned about church. They still believe in traditional theology, he said. But they are also concerned about issues of race and social justice.

“The ‘Holy Post’ speaks to that,” he said.

Vischer feels a sense of loyalty to the evangelical world he was raised in and where his family has a long history. His great-grandfather R.R. Brown was a famed radio preacher and founder of the long-running Okoboji Bible Conference in Iowa. Vischer is a longtime member and former elder at Wellspring, a multiethnic Christian and Missionary Alliance church in Wheaton, Illinois.

“This is my family,” he said. “I’m not going to curse my forefathers. I think, for the most part, they were trying to do the right thing.”

Vischer argues that there’s always been a countercultural side to the evangelical subculture. One of his favorite songs in the 1980s was Steve Taylor’s “I Want to Be a Clone,” a sarcastic look at church culture. And among the early Christian musicians Vischer listened to were Keith Green, Larry Norman and the Resurrection Band.

“These were people who lived in communes,” he said.

During last summer’s protests against racial injustice, sparked by the death of George Floyd, Vischer released a video that unpacked the history of racism in the United States. The video begins with Vischer asking, “Why are people so angry” and then tries to answer that question in about 17 minutes, packed with data from a talk on race in America that his brother gave at the Okoboji Bible Conference.

“The average Black household has one-tenth the wealth of the average white household,” Vischer said in the video. “This didn’t happen by accident. It happened by policy.”

The video on race — and others that have followed — was another step in Vischer’s evolution from trying to be the next Walt Disney to trying to be the best Phil Vischer he can be. That evolution is ongoing.

Until two years ago, most of his income still came from “VeggieTales.” But production on a Trinity Broadcast Network version of the show wrapped up last year and that might be it, said Vischer, at least for the foreseeable future. So he is back to the drawing board, looking for his next projects.

“Every year, I spend about six months making stuff and another six months looking for financing for the next thing I hope to do,” he said. “It’s can be frustrating but it is not a bad life.”

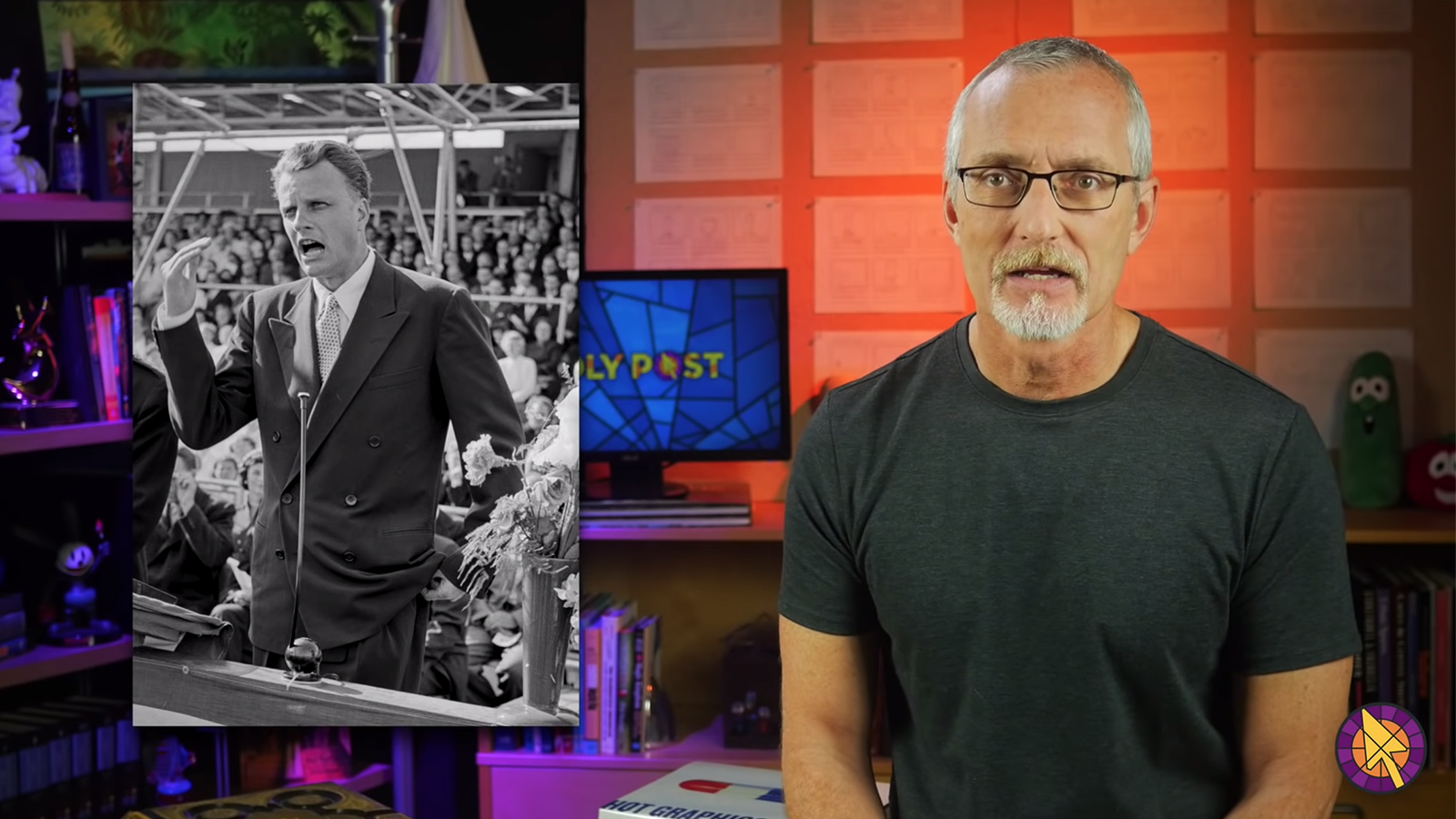

Phil Vischer in a “Holy Post” video titled ‘What is an “Evangelical?”’ Video screengrab

He does still feel the word “evangelical” matters. It represents a kind of Christianity that still resonates with him, one that owes more to “Christianity Today” and Billy Graham and his great-grandfather than to Bob Jones University or Republican politics.

“When I think of the word, I picture something different than most of the world pictures, and I think it’s worth fighting for,” he said.

What gives him joy these days?

“Making stuff,” he said — whether that is creating a show for kids about the Bible or writing songs or researching a video about church history. He enjoys the process of research and writing and then picking up his guitar and ukulele and getting to work. It’s been like that ever since he was a kid.

“I just wanted to sit in the basement and make things,” he said.

If he could talk to his younger self, he’d give a simple message: Slow the heck down.

“It’s not a race,” he said. “God will accomplish what God wants to accomplish. You don’t have to run yourself ragged trying to help him.

Vischer has seen hope for the evangelical movement in his home church. He and co-host Jethani were both members of an older, mostly white Christian and Missionary Alliance congregation that had been in decline for a number of years and had a building that was too big for them.

The church’s future was uncertain.

One day, a denominational leader came to the church with a suggestion. Not far away was another CMA congregation, a growing second-generation immigrant Asian church. What if, the denominational leader asked, the two churches merged?

After two years of prayer and discussion, the two congregations did just that. Today the church is back to about 1,000 people from diverse backgrounds, including Latino and African American families as well as a ton of college students.

Vischer was an elder during the time of the merger, which included a name change. His job during the merger was to urge other white members to do all they could to make the merger work.

“As the dominant culture, we have to bend more,” he said.

Not everything is perfect. The newly merged congregation had to figure out everything from its governance and worship to church potlucks and whether to put up a Black Lives Matter sign at the church.

But a church that was once declining is now growing and has a future.

“It’s been fun,” he said. “That’s what gives me hope. It’s OK if we follow Jesus and let the chips fall where they may.”